.

Dr. Indu Prakash Elhence: The Heartbeat of Surgical Excellence in Agra

In the shadow of the Taj Mahal, where Agra’s timeless beauty meets human resilience, Dr. Indu Prakash Elhence has spent over five decades crafting a legacy as a masterful surgeon and surgical oncologist. Born on July 2, 1939, in the serene town of Amroha, Uttar Pradesh, Dr. Elhence’s journey from a determined medical student to a revered figure in Indian surgery is a story of grit, compassion, and unwavering dedication.

Dr. Elhence’s path began at Sarojini Naidu Medical College, Agra, where he earned his MBBS in 1961 and his Master of Science in Surgery in 1964. Those early years were just the foundation. “I was a bundle of nerves in my first dissection class,” he’d later confess with a grin to his students. “But every cut taught me something new about life.” His thirst for knowledge took him across the globe to Crumpsall Hospital in Manchester, England, where he served as a house surgeon and surgical registrar from 1961 to 1968, honing his skills in high-pressure operating theatres.

He was married to Dr B R Elhence a pathologist, who unfortunately died of cancer long back. I always saw her pouring over a microscope.

Returning to Agra, Dr. Elhence became a cornerstone of Sarojini Naidu Medical College. He rose through the ranks—Lecturer in Surgery (1971–1973), Reader in Surgery (1975–1984), Professor of Surgical Oncology (1984–1990), Professor of Surgery (1990–1994), and finally Chairman of the Department of Surgery (1994–1996). His expertise in surgical oncology, particularly in battling cancer, made him a beacon of hope. “Cancer isn’t just a disease; it’s a fight for someone’s future,” he’d say, his words carrying the weight of countless lives saved.

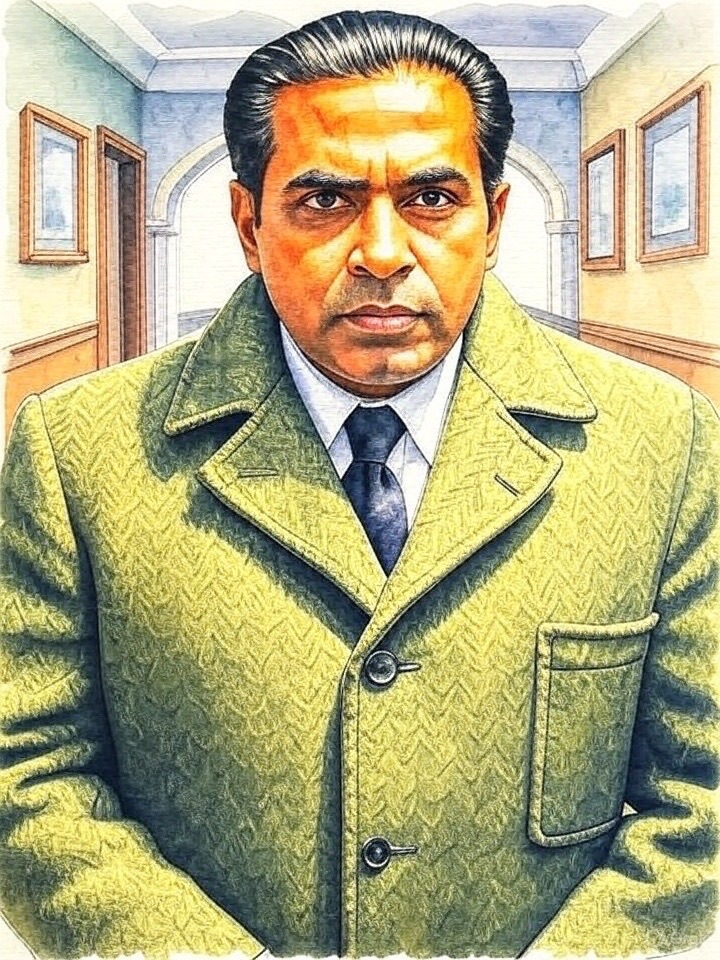

Dr. Indu Prakash Elhence was a figure who commanded both respect and a touch of fear in the halls of the medical college. He wasn’t tall, but his presence loomed large—medium height, skin a deep shade of bronze, with jet-black hair meticulously combed back, always wearing his signature tweed coat, its elbows patched from years of leaning over surgical texts and operating tables. He drove a Fiat, a modest car that matched his frugal lifestyle, and lived in a house nestled within the senior boys’ hostel, where he served as warden. The house built perhaps a hundred years back with thick brick walls and tall ceilings with a untended garden in front mostly full of rose and shrubs was ramshackle just like the senior boys hostel. The red sandstone in the underbelly of earth heated up in Agra sun and afternoon in summer were like standing inside an oven. Perhaps he liked the closeness of his house to his department or being amongst students or it held a sentimental value for him, he didn’t venture for a posh house. Perhaps he wanted it to be like Cherian’s house which in New Zealand was so close to his department that as soon as the lights of his house went out, the staff nurse would call him to to wish him good night or call him if emergency arrived. His wife, a professor of pathology, was his intellectual equal, and together they seemed to live in a world of precision and discipline.

Dr. Elhence was obsessive about details, a trait that defined his surgical practice. They said no patient of his ever died on the table—his cases were prepared with such care that the operating theater felt like a sacred ritual. His lectures were legendary, packed with students scribbling furiously to capture every word. His notes were gold; they weren’t found in Love and Bailey, the standard surgical text, but if you could reproduce his exact words in exams, you’d score high. His questions as an examiner were predictable yet demanding, a test of memory and discipline.

He was a sportsman, a lawn tennis player, and favoured sporting student. He seemed fit and clad in brown half pants and white T shirt with horizontal lining at chest, he went to Agra Club to play tennis whenever time permitted.

But then came the infamous MCQ experiment. The surgery department, under pressure to modernize, briefly switched to multiple-choice question exams. The results shocked everyone. Toppers like me and my friend Khan—usually middle-of-the-pack students—aced it, while the usual stars floundered. The faculty, especially Dr. Elhence, was livid. The MCQ format was scrapped, and the old, grueling long-answer exams returned with a vengeance.

I’ll never forget the day Dr. Elhence summoned me to his office. Sanjay Jasuja, who is now a psychiatrist in America had written a letter demanding MCQ in examination. Unfortunately his hand writing was similar to mine. Rumour had spread that I was the ringleader behind the push for MCQs, and he wasn’t having it. I was terrified as I knocked on his door, the creak of the hinges sounding like a warning.

“Come in,” his voice boomed, sharp as a scalpel.

I stepped into his office, a small room cluttered with books and surgical diagrams. He sat behind his desk, his tweed coat hanging on the chair, his eyes piercing through his glasses.

“Sit,” he said, pointing to a chair. “I hear you’re the one stirring trouble about these MCQ exams. Care to explain yourself?”

My heart sank. “Sir, I swear, it wasn’t me,” I stammered. “I just answered the questions. I am a mediocre student and also don’t aspire for much. I didn’t ask for the change.”

He leaned forward, his gaze unrelenting. “You expect me to believe that? You and that Khan boy topped the exam, and now you’re telling me it’s a coincidence?”

“Sir, I studied your notes,” I said, my voice trembling but earnest. “I didn’t know the exam would be MCQs. I just… got lucky.”

He raised an eyebrow, clearly skeptical. “Lucky? Surgery isn’t about luck, boy. It’s about precision, preparation, and discipline. You think those tick-box questions test that?”

“No, sir,” I said quickly, sensing an opening. “I agree with you. The long answers are better. They make us think.”

He leaned back, his expression softening just a fraction. “Hmm. At least you’re not a complete fool.” He paused, then waved a hand. “Get out. And don’t let me hear your name in any more trouble.”

I practically ran out of his office, my heart pounding but relieved to escape his wrath. From that day on, I made sure to keep my head down and my notes from Dr. Elhence’s lectures pristine. The man was a force of nature, and crossing him was a mistake I wouldn’t make twice.

In the hallowed halls of medical school, where knowledge and nerves collide, Professor I P Elhence stood as a towering figure—both revered and feared. A seasoned general surgeon with a penchant for teaching, he had an uncanny ability to make complex concepts stick, often weaving vivid stories of injuries and their consequences into his lectures. One such lecture, delivered with his characteristic gravitas, was on the obscure yet critical topic of sideswipe injuries—a term that would soon haunt one unsuspecting student.

The lecture hall buzzed that day as Dr. Elhence described the mechanics of sideswipe injuries, where a vehicle’s side-impact collision mangles limbs caught in the chaos, often seen in accidents involving protruding elbows or knees. His words were precise, his diagrams meticulous, but for me, a harried medical student juggling too many notes and too little sleep, the term “sideswipe” slipped through the cracks of my memory like sand through fingers.

Fast forward to the exam. The question paper landed on my desk, and there it was, like a taunt from fate: “Write a short note on sideswipe injuries.” My heart sank. Sideswipe? Was it a fracture? A sprain? A surgical technique? My mind drew a blank. But in the grand tradition of students who know too little, I decided to write—a lot. If I couldn’t dazzle with accuracy, I’d overwhelm with volume. Pen flying, I filled page after page with the ABCs of injury management—airway, breathing, circulation, splints, and a generous sprinkle of generic trauma protocols. Surely, I thought, somewhere in this avalanche of words, I’d scrape half the marks.

Unbeknownst to me, Dr. Elhence was invigilating that day. His presence was impossible to ignore—a tall, bespectacled figure with a quiet intensity, pacing the aisles like a hawk. As I scribbled furiously, I sensed a shadow loom over my desk. There he was, Dr. Elhence himself, peering down at my exam paper. His eyes scanned my pages, lingering a moment too long, as if trying to decipher the puzzle of my rambling prose. I caught his gaze and, in a mix of defiance and desperation, shot him a look that screamed, Don’t distract me, I’m on a roll! With a subtle shake of his head—perhaps a silent warning of the disaster unfolding—he moved on, leaving me to my doomed masterpiece.

When the results came, my heart sank again: a glaring zero. Dr. Elhence, ever the educator, later pulled me aside. “You wrote a novel,” he said, his voice a mix of amusement and exasperation, “but not about sideswipe injuries.” That moment became a turning point. His lecture had been a gift of knowledge; my failure was a lesson in humility and preparation. Dr. Elhence wasn’t just a teacher of bones and joints—he was a sculptor of character, shaping us through moments of triumph and, sometimes, spectacular defeat.

Since 1996, Dr. Elhence has continued his mission as a consultant surgeon and surgical oncologist in Agra, blending precision with empathy. Beyond the operating room, he’s championed community health, leading early cancer detection camps with the Lion’s Club in Maihpur (1988–1989) and driving anti-tobacco initiatives with the Indian Council of Medical Research (1999–2000). His global influence shines through his roles as a visiting professor at St. Luke’s University Medical School, Chicago (2002), and Subharti Medical College, Meerut (2004), as well as his governorship at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, since 2003.

Dr. Elhence’s accolades are as vast as his impact: Fellow of the American College of Surgeons, National Academy of Medical Sciences (delivering the prestigious National Oration in 1988 and 2003–2004), Association of Indian Surgeons, Indian Academy of Medical Sciences, and Royal College of Surgeons, England. Yet, for him, the true reward is the trust of his patients and the spark in his students’ eyes.

A Lively Chat with MBBS Students

It’s a crisp morning in 2025 at Sarojini Naidu Medical College, Agra. The lecture hall hums with anticipation as MBBS students crowd around Dr. Indu Prakash Elhence. At 85, his presence is electric, his stories a bridge between textbooks and real-world medicine. The session feels more like a fireside chat than a formal lecture.

Student 1 (eagerly): “Sir, how do you handle the stress of a life-or-death surgery? I can barely keep my hands steady in practicals!”

Dr. Elhence (with a warm laugh): “Trust me, I wasn’t steady either in my early days in Manchester! Picture this: 1962, my first major surgery, and my hands were shaking like a leaf. The trick? Breathe deeply and focus on the patient, not the scalpel. Think of it as solving a puzzle where every piece matters. You’ll find your calm.”

Student 2 (hesitant): “Sir, working in oncology… doesn’t it break your heart sometimes? How do you keep going?”

Dr. Elhence (eyes softening): “It does. I’ve sat with families through the hardest moments, and it never gets easier. But you learn to carry it. After a tough day, I’d walk along the Yamuna, let the river wash away the heaviness. You keep going because the next patient needs your best. Find your anchor—music, family, anything that reminds you why you started.”

Student 3 (grinning): “Any survival tips for us drowning in med school, sir?”

Dr. Elhence (winking): “Oh, you’re not drowning—you’re swimming toward something extraordinary! Study hard, but listen harder. Your patients will teach you more than any book. Ask ‘why’ relentlessly, and don’t skip meals—trust me, a hungry doctor is a grumpy doctor!”

The students burst into laughter, pens scribbling, hearts ignited. Dr. Elhence’s life—woven through Agra’s medical landscape—is a testament to skill, empathy, and an unyielding commitment to healing. He’s not just a surgeon; he’s a storyteller, a mentor, and a lifeline for a city that holds him dear.