In the crisp autumn of 1969, Gandhi Road in Dehradun buzzed with the kind of excitement that only a new beginning could spark. Our wholesale paper ream shop, a modest dream of my brother Pradeep and me, Prem Prakash, was about to open its doors. The air smelled of fresh paint and the promise of prosperity, and the crowd gathered outside our storefront was a mix of curious locals, eager suppliers, and a few well-wishers. But the real star of the day was Mahant Indresh Charan Das, a revered figure in the city, who had graciously agreed to inaugurate our shop.

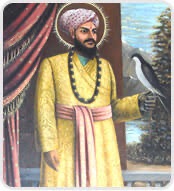

I still remember the moment he arrived. The chatter of the crowd hushed as a sleek black Ambassador rolled up, its chrome glinting in the October sun. Out stepped Mahant Indresh, resplendent in princely robes that seemed to belong to another era. His silken kurta shimmered in shades of ivory, paired with a flowing dhoti that swayed with every step. Over it, an intricately embroidered achkan hugged his frame, its deep maroon hue catching every eye. A regal cap, adorned with a single peacock feather, sat proudly on his head, and his pointed beard and twirled moustaches framed a face that radiated both wisdom and warmth. He carried himself like royalty, yet his eyes twinkled with a kindness that put everyone at ease.

“Prem, !” he called out as he approached, his voice rich and resonant, cutting through the murmurs. “What a fine venture you’ve embarked upon! Paper, the lifeblood of knowledge, deserves a grand beginning.”

I felt a flush of pride as I shook his hand, his grip firm yet gentle. “Mahant ji, we’re honored you’re here,” I said, trying to keep my voice steady. “This shop is our dream, and your presence makes it feel… blessed.”

Pradeep, ever the more confident one, chimed in, “We’ve got big plans, Mahant ji. Dehradun’s schools, offices, they’ll all come to Prem Prakash Pradeep Kumar for their paper!”

Mahant Indresh chuckled, his beard quivering slightly. “Bold words, young man! I like that spirit. Now, where’s this ribbon you want me to cut? Let’s not keep knowledge waiting.”

The crowd parted as we led him to the entrance, where a crimson ribbon stretched across the doorway, tied with a neat bow. A young boy from the neighborhood, no older than ten, scurried forward with a silver-plated scissor on a velvet cushion, his eyes wide with awe. Mahant Indresh took the scissor, holding it up for the crowd to see, the metal catching the light.

“To new beginnings,” he said, his voice carrying a solemn weight, “and to the power of words, which this shop will help spread.” With a swift, graceful motion, he snipped the ribbon, and the crowd erupted in applause. Women in colorful sarees tossed marigold petals, and the sound of a conch shell echoed from somewhere nearby, adding to the festive air.

Inside, we’d set up a small table laden with snacks—crisp samosas, golden jalebis, and steaming cups of masala chai. Mahant Indresh mingled effortlessly, chatting with everyone from grizzled shopkeepers to wide-eyed children. “This is delicious,” he said, biting into a samosa, crumbs catching in his beard. “Prem, you’ve not only opened a shop but a gathering place for the community!”

I laughed, feeling a warmth spread through me. “That’s the hope, Mahant ji. We want this to be more than just paper reams.”

As the afternoon wore on, he shared stories of Dehradun’s past, of its quiet charm before the city grew, and of his own work at the local college, where he nurtured young minds. “Knowledge is like a river,” he said at one point, his eyes gleaming. “It flows, it shapes, it transforms. You boys are now part of that river.”

The memory of that day stayed vivid, a golden moment in time. But years later, I heard a shocking tale about Mahant Indresh that shattered the image of that serene afternoon. It was whispered in hushed tones across Dehradun’s markets: a lunatic teacher from his own college, driven by some twisted grudge, had attacked him. The details were gruesome—stabbed in the abdominal wall, a brutal wound meant to kill. But what stunned me most was the bizarre claim that followed: the assailant, in a deranged frenzy, had stuffed lime—ordinary, caustic lime—into the incision, as if to mock or torment him further.

I couldn’t believe it at first. “Lime?” I said to Pradeep when he told me, my voice thick with disbelief. “Who does something like that?”

Pradeep shook his head, his face grim. “They say the doctors at Doon Hospital worked for hours to clean it out. The lime… it was burning him from the inside, Prem. Can you imagine the pain?”

I couldn’t. The image of Mahant Indresh, so regal and composed, clashed violently with the thought of him fighting for his life, doctors painstakingly removing the corrosive substance from his wound. “Did he… survive?” I asked, dreading the answer.

Pradeep sighed. “I don’t know. Some say he pulled through, others say he didn’t. You know how rumors are in this town.”

I nodded, but the uncertainty gnawed at me. I pictured Mahant Indresh, his princely robes replaced by a hospital gown, his commanding presence reduced to a battle against pain and madness. Yet, in my mind, he remained the man who blessed our shop, who spoke of knowledge as a river. I hoped, wherever he was, that river still flowed.

Biography of Mahant Indresh Charan Das

Personal Details

THE NINTH SHRI MAHANT INDIRESH CHARAN DASS JI

Illustrious personages and saints are born to awaken the common people, to create wisdom in them, to work for the welfare and peace of the society and to preach the absolute essence of a righteous life. This applies to the ninth Shri Mahant, late Shri Indiresh Charan Dass Ji, of Shri Guru Ram Rai Ji Maharaj. A man in the street may live only for himself and his family but a greatman or a saint like late Shri Mahant Indiresh Charan Dass Ji, is born for the upliftmen of the masses. Such genius and extraordinary personalities don’t need any kind of publicity or advertisement at all. People get attracted towards them spontaneously. Their life is full of exceptional qualities.

Shri Mahant Indiresh Charan Dass Ji was born on the 14th November 19l9 in village Khamana, Patti Dhangu, District Garhwal, in a poverty-stricken family. He was the only son of Pandit Dayadhar Kukreti and Shrimati Maheshwari Devi. He was born after his two sisters. His parents named him Shridhar Prasad. He had also one younger sister.

- Name: Mahant Indresh Charan Das Ji Maharaj (referred to as “Brahmleen” in some sources, indicating he is deceased).

- Role: Sajjada Nashin (spiritual head and chief trustee) of Darbar Guru Ram Rai, a prominent religious and philanthropic institution of the Udasi sect in Dehradun, Uttarakhand.

- Tenure: Active as Mahant at least through the mid-20th century, with significant involvement noted in the 1940s–1960s (based on legal cases) until his death before June 25, 2000, when his disciple Mahant Devendra Dass succeeded him.

- Death: Mahant Indresh Charan Das passed away before June 25, 2000, as confirmed by records stating that Mahant Devendra Dass took over as Mahant after his demise.

- Specifics Unavailable: No explicit details about his birth date, early life, education, or family are provided in the sources. As a Mahant of the Udasi sect, he likely led a life of celibacy, as is customary for the heads of Darbar Guru Ram Rai, who dedicate their lives to spiritual and societal service.

Role as Sajjada Nashin

- Position: As Sajjada Nashin, Mahant Indresh Charan Das was the spiritual and administrative head of Darbar Guru Ram Rai, a religious institution founded by Guru Ram Rai, the eldest son of the seventh Sikh Guru, Guru Har Rai, in 1676. The Darbar is a key center of the Udasi sect, which blends Sikh and Hindu traditions, emphasizing philanthropy, education, and spiritual practice.

- Responsibilities: He managed the Darbar’s extensive properties, religious activities, and charitable initiatives. The role involved overseeing endowments, maintaining the institution’s traditions, and representing it in legal and public matters. The Darbar’s properties, historically endowed by the Rajas of Garhwal and continued by Gorkha rulers, were under his stewardship, as noted in legal records.

- Succession: Mahant Indresh Charan Das accepted Mahant Devendra Dass as his disciple on February 10, 2000, an event celebrated annually as Devendra Dass’s “Appearance Day.” Following Indresh Charan Das’s death, Devendra Dass became the Mahant on June 25, 2000.

Contributions

- Educational Initiatives: Mahant Indresh Charan Das is credited with founding the Shri Guru Ram Rai Education Mission in 1952. This mission has grown to manage over 122 educational institutions across Northern India, offering education from nursery to Ph.D. levels in both English and Hindi mediums, including professional courses in management, pharmacy, computer applications, life sciences, agriculture, and commerce. The mission’s goal was to provide affordable, quality education to all societal classes, significantly contributing to Uttarakhand’s literacy rate (72.28% as noted).

- Healthcare Legacy: The Shri Mahant Indresh Hospital in Dehradun, a 1,500-bed multi-specialty teaching hospital, is named after him, reflecting his influence on the Darbar’s philanthropic efforts. While the hospital’s establishment date isn’t specified, it aligns with the Darbar’s tradition of societal service under his leadership. The hospital offers advanced medical services, including diagnostics, ICUs, and rural health centers.

- Philanthropic Leadership: As a leader of the Udasi sect, he upheld the Darbar’s tradition of serving society, continuing the legacy of Guru Ram Rai. His work focused on blending spiritual leadership with practical contributions to education and healthcare, as seen in the Darbar’s ongoing initiatives.

Legal Involvement

- U.P. Agricultural Income-tax Case (1940s–1960s): Mahant Indresh Charan Das was involved in a legal dispute under the U.P. Agricultural Income-tax Act for the year 1355 Fasli (~1945–46). He argued that the agricultural income from the Darbar’s properties was exempt under Section 8, as it belonged to the Darbar (a juridical entity) and not him personally. The assessing authority initially accepted this for some years (1355, 1356, 1361–1363 Fasli), but for 1357–1360 Fasli, he was held liable, and his appeals were dismissed. A 1971 Allahabad High Court ruling clarified that the Darbar’s property was held by the Mahant as a representative, not an owner, reinforcing the institution’s legal status as a mutt under Hindu law.

- U.P. Large Land Holdings Tax Case (1971): Another case involved the U.P. Large Land Holdings Tax Act, 1957, where Mahant Indresh Charan Das challenged tax assessments for 1363 Fasli. The Allahabad High Court quashed the assessment orders (dated January 25, 1961, December 28, 1961, and November 28, 1967), affirming that the property belonged to the Darbar, not the Mahant personally. This case highlighted the Darbar’s historical endowments and its status as a religious institution.

- Significance: These legal battles underscore his role in protecting the Darbar’s assets and clarifying its juridical status, ensuring its properties were recognized as held in trust for religious and charitable purposes.

Historical and Cultural Context

- Darbar Guru Ram Rai: Founded in 1676 by Guru Ram Rai, the Darbar is a significant institution of the Udasi sect, known for its unique blend of Sikh and Hindu practices. The Darbar’s architecture reflects Indo-Islamic influences, with domes, minarets, and Mughal-style gardens, distinguishing it from typical gurdwaras. It historically controlled much of Dehradun’s land, requiring even British permission for access during colonial times.

- Udasi Sect: The Udasi sect, to which the Darbar belongs, reveres Guru Ram Rai as a saint and incorporates Hindu practices like samadhi worship and rituals such as ringing bells and waving lights. Mahant Indresh Charan Das, as a leader of this sect, would have overseen these practices, maintaining the Darbar’s spiritual and cultural traditions.

- Endowments: The Darbar’s properties were endowed by the Rajas of Garhwal, not directly by Emperor Aurangzeb, as clarified in legal records. These endowments supported religious activities like daily puja and sadabrat (charitable feeding), which Mahant Indresh Charan Das managed.

Legacy

- Institutional Growth: Under his leadership, the Darbar expanded its societal impact through education and healthcare. The Shri Guru Ram Rai Education Mission and Shri Mahant Indresh Hospital are lasting testaments to his vision of affordable education and healthcare for all.

- Spiritual Influence: As the ninth Mahant (per a YouTube source), he continued the Darbar’s tradition of spiritual leadership, guiding devotees and maintaining the institution’s reverence for Guru Ram Rai.

- Successor: His disciple, Mahant Devendra Dass, continues his legacy, emphasizing societal service and expanding the Darbar’s initiatives, such as healthcare access in remote areas.

Clarifications on Potential Confusion

- Possible Misinterpretation: If you meant Charan Das Mahant (the politician) or Sant Charandas (the 18th-century saint), here’s a brief distinction to confirm:

- Charan Das Mahant (born 1954) is a Congress politician, currently Chhattisgarh’s Leader of Opposition, with a background in agriculture and education (M.Sc., M.A., LL.B., Ph.D.). He’s unrelated to the Darbar Guru Ram Rai.

- Sant Charandas (1703–1782) was a Vaishnav saint who founded the Caraṇdāsī sect, focused on Krishna devotion, and wrote on yoga and Upanishads. He’s a historical figure, not connected to the 20th-century Mahant.

- Typo Check: If “undress” in your previous query was meant to be “Indresh,” the focus on Mahant Indresh Charan Das seems correct. If you meant something else, please clarify.

- Charan Das Mahant: A distinct individual, Charan Das Mahant (born 1954) is a Congress politician and Leader of Opposition in Chhattisgarh, with no connection to the Darbar Guru Ram Rai. He is an agriculturist and writer, educated at Bhopal University.

- Sant Charandas: A 17th–18th-century Vaishnav saint (1703–1782) who founded the Caraṇdāsī sect, unrelated to Mahant Indresh Charan Das or the Udasi sect.

- Ram Charan: An Indian actor and producer in Telugu cinema (born 1985), unrelated to the Darbar or Mahant Indresh Charan Das.

Limitations and Gaps

- Missing Details: Specifics about Mahant Indresh Charan Das’s birth, early life, or personal background are absent from available sources, likely due to the Udasi tradition of Mahants avoiding self-praise and focusing on service, as noted in Darbar records.

- Source Constraints: Most information comes from legal cases and institutional websites, with limited personal anecdotes. A YouTube video from 1996 mentions him as the ninth Mahant but lacks detailed biographical content.

Further Research Options

If you seek more details, I can:

- Analyze additional sources or X posts for references to Mahant Indresh Charan Das or the Darbar’s history.

- Provide a deeper history of the Darbar Guru Ram Rai or the Udasi sect.

- Explore specific aspects, like the Education Mission’s growth or the hospital’s development, if you have a particular focus.

Please let me know if you want me to dive deeper into any aspect or if you meant a different individual or topic!

Biography of Mahant Indresh Charan Das

Role and Context:

Mahant Indresh Charan Das was the Sajjada Nashin (spiritual head or chief trustee) of Darbar Guru Ram Rai, a significant religious institution, likely linked to the Udasi Sikh or Hindu spiritual tradition centered around Guru Ram Rai, the eldest son of Guru Har Rai, the seventh Sikh Guru. The Darbar, located in Dehradun (now in Uttarakhand, formerly part of Uttar Pradesh), is a prominent religious and cultural center managing properties and spiritual activities.

Legal Case Reference:

The primary source of information about Mahant Indresh Charan Das comes from a 1971 legal case under the U.P. Agricultural Income-tax Act (for the year 1355 Fasli, ~1945–46). As the Mahant, he was responsible for managing the Darbar’s properties, which generated agricultural income. He claimed tax exemptions under Section 8 of the Act, arguing that the income belonged to the Darbar (a juridical entity, akin to a mutt or religious trust) and not to him personally. The assessing authority initially accepted this for certain years (1355, 1356, 1361–1363 Fasli), closing tax proceedings. However, for the years 1357–1360 Fasli, he was held liable for taxes, and his appeals were dismissed. The case underscores that the Darbar’s property was held in trust, with the Mahant acting as its representative, not the personal owner.

The Benevolent King of Dehradun: The Life and Legacy of Mahant Indresh Charan Das

In the misty valleys of Uttarakhand, where the Himalayas stand as silent guardians, there once ruled a man who embodied the spirit of a bygone era of benevolent kingship. Mahant Indresh Charan Das, the ninth Mahant of the revered Shri Guru Ram Rai Darbar Sahib in Dehradun, was no ordinary spiritual leader. With his regal bearing—tall, commanding, and exuding an aura of quiet authority—he walked among his people like a charmer from ancient tales, drawing devotees and the downtrodden alike into his orbit. Born into humble roots in the rugged terrains of what is now Uttarakhand, Indresh Charan Das rose through the ranks of the Udaseen sect, a celibate order devoted to service and spirituality. He wasn’t schooled in the sciences or modern management like his successor, the current Mahant Devendra Das Ji Maharaj, who oversees a more formalized empire of education and healthcare. No, Indresh was a man of the soil, guided by instinct, faith, and an unyielding compassion that made him a living legend. Yet, his story is one of profound generosity shadowed by tragedy—a tale that still echoes in the whispers of patients and pilgrims who visit the darbar today.

A Rustic Rise to Royal Philanthropy

Indresh Charan Das’s journey began in the early 20th century, amid the freedom struggle that swept India. A freedom fighter at heart, he channeled his fervor into building institutions that would uplift the masses. In 1952, he founded the Shri Guru Ram Rai Education Mission, a visionary endeavor that started with a handful of schools and ballooned into a network of over 128 institutions across northern India, particularly in Uttarakhand. These weren’t just classrooms; they were beacons of hope for poor village children, offering English-medium education at nominal fees. “Education for all,” he would say, his voice booming like a king’s decree in the darbar’s grand hall. Unlike a corporate CEO crunching numbers, Indresh managed the darbar’s vast lands, shops, and properties with the wisdom of a feudal lord—fair, firm, and fatherly.

His philanthropy knew no bounds. The darbar, under his stewardship, became a veritable kingdom of charity. He doled out properties to the needy on meager rents, turning idle shops into lifelines for struggling families. Stories abound of his daily durbar, where he held court like a benevolent monarch, listening to petitions from dawn till dusk. One elderly patient recently shared with me, eyes misty with gratitude: “I was a young widow back then, barely scraping by after my husband’s death. We had nothing—no roof, no means. Desperate, I approached Mahant Ji in the darbar. Trembling, I fell at his feet and poured out my woes: ‘Maharaj, my children are starving; we’ve lost everything to illness and debt.’ He looked at me with those kind, piercing eyes, placed a hand on my head, and said, ‘Beta, the Guru’s blessings are for all. Take this shop—run a small tea stall there. Pay what you can, when you can. Let it be your new beginning.’ That shop became our salvation; we paid a pittance in rent, and it fed us for generations.” Such anecdotes are legion, humanizing a man who, despite his kingly stature, saw himself as a humble servant of the divine.

Indresh’s charm lay in his accessibility. He wasn’t aloof like modern executives; he was the people’s king, charming them with folksy wisdom and a rustic humor that lightened even the heaviest burdens. Devotees recall how he’d crack jokes during charity distributions, saying, “If the Guru gave us these lands, who am I to hoard them? Share the bounty, or the mountains themselves will remind us of our greed!” His efforts extended beyond education—he ran free kitchens (sadabrats), medical relief camps, and festivals like the annual Jhanda Mela, fostering a sense of community in a region plagued by poverty and isolation.

Shadows of Power: Enemies and a Fateful Betrayal

But no throne is without thorns. Indresh’s power—over hundreds of schools, vast estates, and a devoted following—bred envy. He had his detractors, chiefly disgruntled teachers discharged for misconduct or inefficiency. Whispers in the corridors of the darbar spoke of “madmen” among them, harboring grudges that festered like open wounds. These weren’t faceless foes; they were once part of his inner circle, employees who felt the sting of his unyielding sense of justice.

Tragedy struck on that fateful day in the darbar’s heart. A known figure—likely a former employee, seething with resentment—approached the durbar under the guise of seeking blessings. In a flash of rage, he drew a knife and plunged it into Mahant Ji’s abdomen. Chaos erupted. “Blood everywhere!” eyewitnesses later recounted, the grand hall turning into a scene of horror. Devotees and sevadaars (attendants) restrained the attacker, but the damage was done—the blade had punctured Indresh’s abdominal cavity, spilling lifeblood onto the sacred floors.

In the panic, Indresh’s rustic upbringing shone through—a testament to his unlettered, instinct-driven wisdom from an era before antibiotics. Writhing in agony, he gasped to his sevadaars, “Quick! Bring chuna—quick lime! Stuff it in; it will seal the wound, like our ancestors did in the fields when no healers were near.” They obeyed, pushing the lime through the gash in a desperate bid to staunch the bleeding, much like ancient antiseptics used in battlefields when modern medicine was a distant dream. It was a human moment of raw survival, revealing the man behind the mahant: not a scientist, but a survivor forged by the hills.

Rushed to the operation theater, surgeons faced a nightmare. Cleaning the abdominal cavity of the caustic lime was grueling; it had burned tissues and complicated the repair. “It was like excavating a battlefield wound,” one doctor confided years later. Miraculously, his life was saved, but the injury left lasting scars. He never fully recovered, his once-kingly frame weakened by complications. A few years later, in the quiet embrace of the darbar he loved, Mahant Indresh Charan Das passed away, leaving behind a legacy that outshone his enemies.

An Enduring Echo

Today, as patients flock to the Shri Mahant Indiresh Hospital—established in his honor by his successor—they still share tales of the “old Mahant Ji,” the charmer who ruled with heart over head. Unlike the current Mahant, educated in modern ways and steering the institution toward technological heights, Indresh was the soul of benevolence, a philanthropist king in an age of change. His story reminds us that true power lies not in titles or degrees, but in the quiet acts of kindness that ripple through generations. In the durbar’s timeless halls, his spirit endures, whispering: “Serve, and the Guru will provide.”

Historical Context:

The title “Mahant” indicates a high-ranking position within a religious institution, often involving both spiritual and managerial duties. The Darbar Guru Ram Rai, established in the 17th century, is known for its historical significance, including the Gurdwara Sri Guru Ram Rai Darbar Sahib in Dehradun. Mahant Indresh Charan Das, active in the mid-20th century based on the legal case, would have played a key role in maintaining the Darbar’s legacy during his tenure.

Mahants & Gurus

The head of Darbar Sahib, called Sajjada Nashin Shri Mahant leads a life of celibacy and dedicate his life for the noble cause of the society.

Rishi-munis, sages-saints, hermits-ascetics and great souls do not need introduction. Their personality and performance leave a permanent impression on the society by itself and people are drawn towards them through their magnetic attraction.

Most probably, this might have been the reason why our hermits and saints never said or wrote anything about themselves. Self-praise is not a quality of saints. It is not a virtue at all. They remained so busy in seeking the subtle truth and benevolence that they were not even conscious of their own importance. The contact of the common people with them was limited to get their blessings and have “darshan”. People remained busy in earning their livelihood and as such, the dates of birth and death anniversaries of most of those great souls were forgotten. But the saying, “By their fruits ye shall know them,” applies to them and cherishes such great persons. For want of any record of their dates of birth, education etc., the statements of the aged, their preachings, popular acceptances and assumptions can only be considered its basis. It is enough for the curious to know the history of their life and work. We remember those great souls by turning the pages of that history based on inferences.

Shri Guru Ram Rai Ji Maharaj left for his heavenly abode in 1687 and the work of the Darbar Sahib was then managed by Mata Punjab Kaur. In those days women were forbidden to occupy the seat (Gaddi) of a religious sect or a Mahant, hence she carried on the work with the help of an experienced assistant and devotee of the Darbar Sahib, Shri Aud Dass Ji, and the chief employee, Shri Har Prasad Ji. Shri Aud Dass Ji was declared as the first Shri Mahant. He had worked under the guidance of Shri Guru Ram Rai Ji and he had gained a lot of experience.