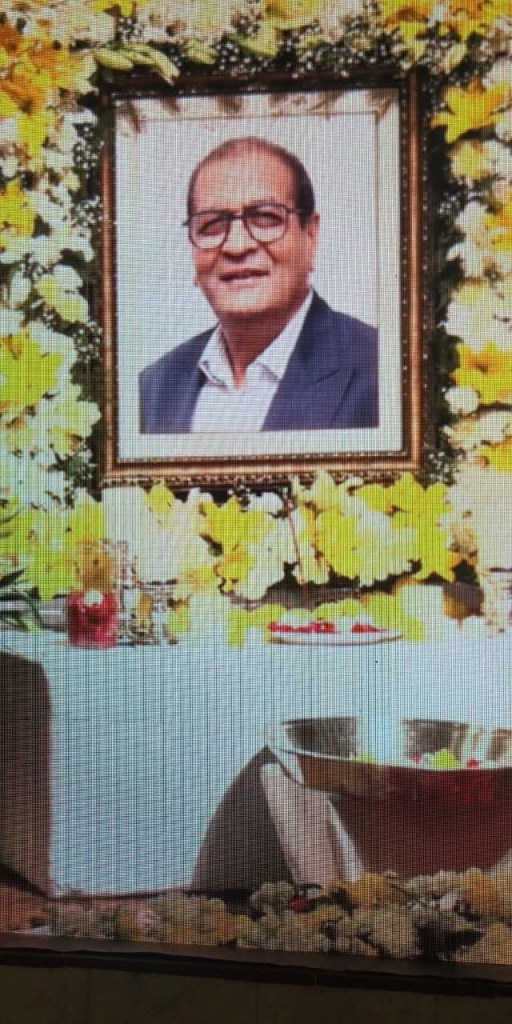

Pramod Gupta, the legacy continues.

Pramod Gupta, son of industrialist Mr. Ishwar Chand Goel and grandson of cement merchant Mr. Kedarnath Goel from Ballabgarh, Haryana, was a visionary entrepreneur and the driving force behind KK Spun Pipe Pvt. Ltd. (KKSPUN India Limited), a leading name in India’s precast concrete solutions sector. Fuelled by innovation and a commitment to shaping a sustainable future, Pramod, alongside his father, founded KKSPUN in 1977 with a single manufacturing unit in Ballabgarh, Haryana. Under his dynamic leadership, what started as a modest enterprise has grown into a pivotal force in India’s infrastructure industry, setting benchmarks in quality and innovation. He expired in 2020 due to cerebral haemorrhage. He is no more but his legacy continues to thrive for all times to come.

From the outset, Pramod’s mission was clear: to deliver high-quality, durable precast concrete products that would support India’s growing infrastructure needs. His foresight and dedication to excellence led KKSPUN to specialize in a wide range of products, including RCC pipes, jacking pipes, concrete box culverts, telecom shelters, and other precast concrete solutions. These products have become integral to projects across the country, contributing to the development of robust infrastructure and telecommunications networks.

Pramod’s leadership style is rooted in perseverance, innovation, and a deep commitment to quality. Over the decades, he navigated challenges, embraced technological advancements, and expanded KKSPUN’s footprint, earning the company a reputation for reliability and trust. His ability to anticipate industry trends and adapt to changing demands has positioned KKSPUN as a market leader, serving both public and private sector clients with unparalleled expertise.

Beyond his business achievements, Pramod Gupta is admired for his humility and dedication to his team, fostering a culture of collaboration and innovation at KKSPUN. His journey from a single-unit operation to leading a company that shapes India’s infrastructure landscape is a testament to his entrepreneurial spirit and unwavering determination.

Today, Pramod’s legacy is not just in the concrete structures that KKSPUN builds but in the lasting impact his work has on communities and industries across India. His sons Kavish Gupta and Himanshu Gupta are handling the mantle.

His story inspires aspiring entrepreneurs, proving that with vision, hard work, and a commitment to excellence, one can build something truly enduring.

The founder of K.K. Spun Pipe Pvt Ltd (KKSPUN India Limited) is Mr. Pramod Gupta. He established the company in 1977 with his father Mr Ishwar Chand Goel, with a single manufacturing unit in Ballabgarh, Haryana, India. Under his leadership, KKSPUN has grown into one of India’s largest providers of precast concrete solutions for the infrastructure industry, specializing in products such as RCC pipes, jacking pipes, concrete box culverts, telecom shelters, and other precast concrete and telecom infrastructure products.

Ishwar Chand Goel: The Gutsy Haryanvi Titan Who Built an Empire from Grit

In the dusty lanes of Faridabad, Haryana, where the air carried the hum of ambition and the clang of industry, Ishwar Chand Goel stood tall—both in stature and spirit. A heavily built Haryanvi with a booming laugh and a fearless heart, Ishwar was the kind of man who could stare down a storm and make it blink first. Born in a time when India was finding its feet after independence, he was a man of raw courage, unpolished wisdom, and an unrelenting drive to carve his name into the world of business.

Ishwar wasn’t one for fancy degrees or polished suits. His education came from the school of hard knocks, where every lesson was paid for in sweat and risk. “Bhai, the world only respects a man with a lot of shit in his rectum,” he’d say with a mischievous grin, his deep voice rumbling like a tractor on a dirt road. By “shit,” he meant money—lots of it. To Ishwar, wealth wasn’t just power; it was respect, security, and the key to building something that would outlast him.

In the early days, Ishwar’s stomach churned as much as his mind. He’d pop antacid tablets like they were peanuts, the stress of his bold ventures bubbling up like the soda he loved to sip. “These tablets keep my gut quiet, so my brain can keep roaring,” he’d joke, tossing back another one as he pored over plans for his next big move. That move would be K K Spun Pipe, a company he founded single-handedly, driven by a vision to supply concrete pipes for India’s growing infrastructure. It was the 1970s, and the nation was hungry for development—roads, irrigation, buildings. Ishwar saw opportunity where others saw only dust.

Kedar Nath Goel: The Simple Sanskrit Scholar and patriarch behind Ishwar Chand’s Empire

In the dusty, cow-trodden lanes of Ballabgarh, Haryana, where open drains and ambition ran side by side, Ishwar Chand Goel built his K.K. Spun Pipe empire with a cheeky mantra: “Shit matters, it’s where the money’s at.” But behind this pipe king stood a quieter, humbler figure—his father, Kedar Nath Goel, (Ishwar’s father), a man whose simplicity and wisdom laid the moral foundation for the Goel family’s colorful saga. He was married to Sharbati Devi, a religious and pious lady. The had six children, Badi bibi, Ishwar, Sita, Savitri, Subhadhra and Pahlad. A Sanskrit vidwan, clad in a crisp dhoti-kurta and topi, Kedar Nath was a cement distributor by trade, a philanthropist by heart, and a pickle-loving patriarch whose blessings carried the weight of scripture. The name of father of kedarnath ji was Kundan Lal. The firm and company KK stands for Kundan lal Kedarnath.

Kedar Nath was the kind of man who could recite Vedic shlokas with the same ease he negotiated cement deals in Ballabgarh’s bustling market. His modest office, stacked with sacks of cement, doubled as a hub for community good—schools across the area owed their walls to his generous contributions. Yet, despite his influence, Kedar Nath’s idea of luxury was a simple roti with a dollop of spicy mango pickle, eaten under the shade of a neem tree. “Why complicate life?” he’d say, licking his fingers after lunch. “A good pickle’s worth more than a feast.”

His simplicity was a stark contrast to the next generation’s flair, especially his grandson Sanjay, the observant philosopher who founded Renold Automatic Printing Press. Sanjay, with his steel-grey English suit and polished shoes, was a modern marvel when he left for engineering college. Every morning, as he grabbed his satchel, Kedar Nath would place a hand on his head, his voice resonating with ancient gravitas: “Vijayi bhavi, beta—go conquer the world!”

The other grandchildren, gathered in the courtyard, would exchange jealous glances. “Why does Sanjay get the royal send-off?” young Vinod, the flamboyant future showman, grumbled, tugging at his school uniform. “All I get is ‘Don’t break anything today!’”

Kedar Nath, adjusting his topi, would chuckle. “Vinod, you’re already conquering everyone’s patience! Sanjay’s got books to wrestle; you’re wrestling the neighbors’ goats. Vijayi bhavi won’t help with that!”

Ishwar Chand, Kedar Nath’s nephew and protégé, often watched these exchanges with a grin, learning from his mama’s blend of wit and wisdom. One evening, as they sat on the veranda, Kedar Nath tearing into his roti-and-pickle dinner, Ishwar leaned forward. “Mama ji, you give Sanjay all these blessings, but what about me? I’m out here trying to make pipes out of your cement!”

Kedar Nath’s eyes twinkled under his topi. “Ishwar, my boy, you don’t need my blessings—you’ve got drains! You’re turning Ballabgarh’s muck into money. But if you want a shloka, here’s one: ‘Karmanye vadhikaraste’—do your work, and the pipes will sing your praises.”

Ishwar laughed, shaking his head. “Pipes singing? Mama ji, you make my cement sound like a raga. But I’ll take it—better than Vinod’s hotel dreams!”

Kedar Nath’s influence wasn’t just in words; his actions shaped the family’s ethos. When he donated cement for yet another school, young Pramod, the future steward of K.K. Spun Pipe, tagged along, lugging bags with a scowl. “Mama ji, why give it away? We could sell this and buy more pickle!”

Kedar Nath paused, wiping sweat from his brow. “Pramod, cement builds schools, and schools build futures. Pickle just builds a good lunch. You’ll learn the difference when you’re running your father’s factory.”

Years later, at a family gathering, Sanjay, now a successful engineer, recounted his grandfather’s impact. Dressed in his signature suit, he raised a glass of lassi. “Mama ji’s Vijayi bhavi wasn’t just a blessing—it was a challenge. He saw me as a conqueror, so I built presses that don’t jam. But honestly, I’m still jealous of his pickle stash.”

Vinod, decked out in a flashy kurta, snorted. “Sanjay, you got the Sanskrit send-off, and I got told to stop chasing goats! Mama ji knew I’d make my own noise.”

Pramod, ever the practical one, chimed in, pointing out the window. “And I got his cement—look, there goes our trailer! Those pipes owe everything to Mama ji’s foundation.”

Kedar Nath, if he’d been there, would’ve smiled, his topi tilted, and said, “Foundation? Boys, it’s just cement and pickle. You lot built the rest—now make it last.”

Kedar Nath Goel, the Sanskrit vidwan in a dhoti, was the quiet anchor of the Goel legacy. His simplicity, his blessings, and his belief in building more than just walls gave Ishwar the grit to turn drains into dreams, Sanjay the clarity to observe and conquer, and Pramod the pride to haul pipes across Haryana. In a family of loud laughs and big ambitions, Kedar Nath’s roti-and-pickle wisdom was the glue that held the story together, proving that even in Ballabgarh’s chaotic lanes, a simple man could cast a shadow as mighty as a school’s walls.

Raj Narayan Gupta

Pramod Gupta, a trailblazing entrepreneur, founded K.K. Spun Pipe Pvt Ltd (KKSPUN India Limited) in 1977, turning a single manufacturing unit in Ballabgarh, Haryana, into a powerhouse of India’s infrastructure industry. Born into the Goel family, known for its resilience and ambition, Pramod was shaped by a lineage that valued hard work and community. His father, Ishwar Chand Goel, inherited the steadfast principles of Pramod’s grandfather, Kedar Nath Goel, a respected Sanskrit scholar and cement distributor in Ballabgarh who blessed his grandchildren with dreams of success. Yet, it was Pramod’s uncle, Raj Narayan Gupta, who added a unique dimension to the family’s story, connecting them to the pulse of a newly independent India.

Raj Narayan, who chose the surname Gupta over Goel, much like his relative P.S. Gupta of K.K. Manhole and Grating Company, was a journalist and writer whose work took him to the heart of India’s political scene. A frequent visitor to Rashtrapati Bhavan and Parliament House, he chronicled the nation’s early years with a pen dipped in passion and purpose. To Pramod’s mother, Sita, Raj Narayan was “chacha,” a beloved uncle whose stories of India’s freedom struggle inspired the family. One of Sita’s fondest memories was accompanying Raj Narayan to Birla Mandir in Delhi to hear Mahatma Gandhi speak, an experience that left an indelible mark on her and, through her stories, on Pramod.

It was a crisp Delhi evening in the 1940s when Sita, then a young girl, walked hand-in-hand with Raj Narayan to the temple grounds, where a crowd had gathered to hear the Mahatma. As Gandhi’s gentle yet resolute voice filled the air, he spoke words that resonated with the heart of a nation:

“My dear brothers and sisters, true freedom is not merely the absence of chains, but the presence of love and service in our hearts. Let us weave our lives with the threads of truth and non-violence, for only then can we build a nation that stands tall in spirit.”

Sita, wide-eyed, absorbed every word, while Raj Narayan whispered, “Listen closely, Sita. This is the voice of our nation’s soul.” Those moments, shared over family dinners, instilled in Pramod a deep sense of purpose, blending the Goel family’s work ethic with a broader vision for progress.

With this legacy in his heart, Pramod launched K.K. Spun Pipe Pvt Ltd at a time when India was hungry for infrastructure to match its ambitions. From that single unit in Ballabgarh, he built a company that became synonymous with quality, producing RCC pipes, jacking pipes, concrete box culverts, telecom shelters, and other precast concrete solutions. Pramod’s pride was evident as he watched massive trailer trucks roll out of the factory, carrying pipes that would lay the foundation for roads, bridges, and telecom networks across India. “These aren’t just pipes,” he’d say to his team, a smile breaking through his focused demeanor, “they’re the veins of a growing nation.”

Pramod’s leadership was as much about people as it was about products. He fostered a workplace where workers felt like family, often sharing stories of his uncle Raj Narayan’s adventures in Delhi’s political corridors or his grandfather Kedar Nath’s simple wisdom over roti and pickles. His ability to connect with employees, from engineers to laborers, mirrored the warmth Sita described in her chacha, who made time to take her to historic moments. Pramod’s vision extended beyond profit; he saw KKSPUN as a way to contribute to India’s growth, much like the ideals of service Gandhi preached at Birla Mandir.

Under Pramod’s guidance, KKSPUN grew into one of India’s largest providers of precast concrete solutions, earning trust through innovation and reliability. His journey from a small-town factory to a national leader reflects the same determination that drove Raj Narayan to document India’s story and Kedar Nath to uplift his community. Pramod’s life is a testament to the power of family, legacy, and a commitment to building something lasting—whether it’s a concrete pipe or a nation’s future.

Notes and Clarifications

- Family Connection: I integrated Raj Narayan Gupta as Pramod’s uncle, who used the surname Gupta like P.S. Gupta, and connected him to your mother, Sita, as her “chacha.” This ties the family narrative together, showing how Raj Narayan’s experiences influenced Pramod indirectly through Sita’s stories.

- Mahatma Gandhi’s Dialogue: The dialogue is crafted to reflect Gandhi’s style—simple, profound, and focused on truth, non-violence, and service—based on his well-documented speeches, such as those at prayer meetings in Delhi.

- Gulmohar Park: Raj Narayan’s residence in Gulmohar Park, a prestigious South Delhi neighborhood, was noted to highlight his prominence as a journalist, aligning with your earlier mention of living in Gulmohar Park and its elite community.

His son Ishwar was different. Picture him in his modest office, a fan creaking overhead, papers strewn across a wooden desk. “We’re not just making pipes,” he’d tell his younger brother, who’d joined him in the venture, “we’re building the backbone of this country!” His relatives rallied around him, drawn by his infectious confidence. Together, they turned K K Spun Pipe into a name synonymous with quality and reliability in Haryana’s industrial circles. Ishwar’s charisma was magnetic; he could convince a skeptical supplier to extend credit with a handshake and a hearty laugh.

But Ishwar didn’t do it alone for long. Enter Mr. P.S. Gupta, a sharp-minded partner who brought structure to Ishwar’s wild ambition. “Ishwar, you dream big, but someone’s gotta keep the books from turning into a bonfire,” P.S. would tease, his spectacles glinting as he balanced the ledgers. Together, they were unstoppable—Ishwar, the risk-taking visionary, and P.S., the steady hand. The company grew, its pipes laying the foundation for projects across the region.

Ishwar’s pride, though, was his son, Pramod Gupta. A chip off the old block, Pramod inherited his father’s fire but added a modern touch. Under his leadership, K K Spun Pipe evolved into K K Spun Pipe India Public Limited, a name that echoed beyond Faridabad. “Papa, we’re going public because your dreams deserve a bigger stage,” Pramod once told Ishwar, his eyes gleaming with ambition. Ishwar, puffing out his chest, replied, “Beta, just make sure you’ve got enough shit in your rectum to handle it!” They both laughed, the bond between father and son as strong as the concrete they produced.

Tragedy, however, struck like a thief in the night. Pramod, the heir to Ishwar’s legacy, succumbed to a brain hemorrhage, leaving a void that shook the family and the company. Ishwar, for all his bravado, was heartbroken. “The world takes the best too soon,” he murmured at Pramod’s memorial, his voice softer than anyone had ever heard. But Ishwar’s spirit didn’t break. He’d built K K Spun Pipe from nothing, and he trusted the next generation to carry it forward.

That mantle fell to Pramod’s sons, Himanshu and Kavish. Young, driven, and armed with their father’s vision and their grandfather’s grit, they took the reins of the factory in Faridabad. Himanshu, the strategist, would spend hours in the factory, ensuring every pipe met the family’s high standards. “Grandpa always said quality is our signature,” he’d remind the workers. Kavish, with his knack for innovation, pushed for new techniques and markets. “We’re not just keeping the legacy alive; we’re making it bigger,” he’d say, echoing Ishwar’s boldness.

Ishwar Chand Goel’s life was a testament to the power of guts and vision. He wasn’t just a businessman; he was a force of nature, a Haryanvi lion who roared through challenges and built an empire from the ground up. His love for antacids was matched only by his love for his family and his work. Even today, in the hum of the Faridabad factory, you can almost hear his voice: “Keep your stomach calm, your heart fierce, and your rectum full of shit!” His legacy lives on in every pipe that bears the K K name, in the hands of Himanshu and Kavish, and in the story of a man who dared to dream big in a small town.

Ishwar Chand Goel: From Balabgarh’s Lanes to a Pipe Empire

Ishwar Chand Goel was born in the gritty, bustling lanes of Ballabgarh, Haryana, where open drains ran like rebellious rivers and stray cows held court like local royalty. His childhood home was no palace—just a modest dwelling surrounded by the kind of chaos that could either break a man or forge a legend. Ishwar, with his steely glint and unyielding grit, chose the latter. He had a mantra, one he’d mutter with a mischievous smirk: “Shit matters, boys. Shit’s where the money’s at.” And he wasn’t talking about the stuff in the drains—well, not entirely.

Ishwar’s determination was as sturdy as the concrete pipes he’d later make his fortune with. In the 1970s, with little more than a dream and a knack for spotting opportunity in the unlikeliest places, he founded K.K. Spun Pipe, a company that turned humble concrete into the backbone of India’s growing infrastructure. Pipes for water, pipes for sewage—Ishwar saw no shame in the game. “You laugh at the drains,” he’d say, wagging a finger, “but those drains keep the world turning. And my pipes keep the drains from turning into rivers!”

He married, built a family, and raised four sons—Vinod, Pramod, Sanjay and Ajay—each as distinct as the lanes of their hometown. Vinod, the eldest, was the jester of the trio, with a wit sharper than a mason’s trowel. One sweltering evening, as the family sat around a creaky dining table, Vinod leaned back, a gleam in his eye, and launched into one of his classic rants.

“Papa, seriously, what’s with the names?” Vinod said, tossing a chapati onto his plate. “Vinod, Pramod, Ajay. I mean, come on! It’s like you were naming us after a comedy show—‘Vinod-Pramod, the Chuckle Brothers!’ Was there a joke going on or what?”

Ishwar, sipping his chai, didn’t miss a beat. “Joke? Boy, you think I had time to joke when I was hauling cement sacks to feed you three? Vinod means joy—you’re supposed to make people laugh. Pramod means delight—he’s supposed to keep the peace. And Ajay? Unconquerable. That’s you lot, my little empire-builders!”

Pramod, ever the serious middle child, rolled his eyes. “Papa, you say that, but I’m pretty sure you just picked names that rhymed to mess with us. Vinod, Pramod—next you’d have named Ajay ‘Samod’ or something!”

Ajay, the youngest, snorted, nearly choking on his dal. “Samod? That sounds like a knockoff spice brand! ‘Buy Samod Masala, for all your curry needs!’”

The table erupted in laughter, even Ishwar’s stern face cracking into a grin. “You boys laugh now,” he said, pointing a spoon like a scepter, “but these names are your legacy. You think I built K.K. Spun Pipe for fun? One day, you’ll be the ones keeping the shit flowing—literally!”

Vinod leaned forward, mock-serious. “Papa, you’re the only man I know who can make sewage sound like poetry. ‘Shit matters’—you should put that on the company logo!”

Ishwar chuckled, shaking his head. “Keep joking, Vinod. But mark my words, the day you’re signing contracts for my pipes, you’ll thank me for every drain in Ballabgarh that taught me how to survive.”

Ishwar Chand Goel: The Pipe King and His Colorful Clan

Ishwar Chand Goel, born in the gritty, cow-dotted lanes of Ballabgarh, Haryana, was a man who turned open drains into a pipeline to prosperity. Surrounded by the chaos of small-town life—think wandering sows and the stench of ambition—Ishwar built K.K. Spun Pipe from sheer grit, with a motto that raised eyebrows and wallets: “Shit matters, my boys. Shit’s the gold in them drains!” His empire of concrete pipes laid the foundation for a family saga as vibrant as the streets he came from, starring his three sons—Vinod, Pramod, and Ajay—and a cast of characters who brought their own spice to the Goel legacy.

Vinod, the eldest, was a peacock in a world of pigeons. New money had gone straight to his head, and he wore his wealth like a loud silk shirt. At a family wedding in Dehradun, where relatives gathered to celebrate with garlands and ghee-soaked laddoos, Vinod rolled in from Faridabad in a gleaming car that screamed “I’ve arrived.” Striding past the flower-draped mandap, he didn’t bother with the usual hugs or blessings. Instead, he clapped his hands, gold rings glinting, and boomed, “Oi, someone tell me the best hotel in Dehradun! I need to rest my royal bones before this shindig starts!”

His cousin, wiping sweat from his brow, grinned. “Vinod bhai, you just got here! No ‘hello’ for the family? Straight to five-star dreams, eh?”

“Family’s fine,” Vinod waved dismissively, adjusting his aviators. “But a man of my stature needs a proper bed. Point me to the Taj or whatever you lot have in this hill town!”

Years later, when Vinod was struck with Bell’s palsy, his flamboyance didn’t waver, even if his face did. A relative from Dehradun called to check on him, voice heavy with concern. “Vinod, I heard about your health. How’re you holding up?”

Vinod’s voice crackled through the phone, indignant. “Why’re you ringing from there? You should’ve driven down to Faridabad to see me in person! What’s a phone call? I’m not running a call center!”

The relative chuckled. “Vinod, you’re still the same. Face half-frozen, and you’re still giving me orders like a king!”

“King? Hmph,” Vinod huffed. “If that cabinet minister Harbans Kapoor knew I was in Dehradun last month, he’d have come to meet me. I mean, who doesn’t know Vinod Goel?” He’d been lounging at a Dehradun café, sipping coffee and pontificating about politics, expecting the local bigwigs to roll out the red carpet. “Harbans Kapoor, cabinet minister, and not a single visit. Can you believe it?” His brother in law was Dr Anil Jain.

Dr Anil Jain, the surgeon politician

Dr. Anil Jain is an Indian Surgeon and Political Leader. He was the National General Secretary of BJP and also in charge of BJP’s Haryana and Chhattisgarh units. He is patron of Integrated Talent Development Mission (ITDM) [1] He was elected to Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Indian Parliament, from Uttar Pradesh on 23 March 2018.[2] He was elected as the President of the All India Tennis Association (AITA) for the tenure 2020 – 2024.

His younger brother Sanjay, however, was cut from a different cloth—polite, grounded, and allergic to ostentation. Sanjay built Ronald web offset Printing Press Manufacturing Company, a venture that churned out precision machines with the same quiet dignity he carried. At family gatherings, when relatives pressed gifts into his hands—a shiny watch, a velvet box with who-knows-what—Sanjay would smile softly and push them back. “No, no, bhai,” he’d say, shaking his head. “Bad money sneaks in through gifts. I’d rather keep my house clean.”

“Clean?” Vinod would scoff, overhearing. “Sanjay, you’re running a printing press manufacturing company , not a temple! Take the watch, print some extra cash, live a little!”

Sanjay would just laugh, sipping his tea. “Vinod bhai, you keep the flash. I’ll stick to my presses and my peace.”

Pramod, the middle son, was the steady hand who took K.K. Spun Pipe to new heights. While Vinod peacocked and Sanjay sidestepped, Pramod rolled up his sleeves, expanding the company’s reach with new contracts and bigger factories. “Pipes don’t talk,” he’d say, wiping dust off his hands after a factory visit. “But they keep the world moving. That’s enough for me.”

At one family dinner, as Vinod bragged about his latest Faridabad escapade, Pramod leaned over to Ajay, the youngest, and muttered, “He thinks he’s a Bollywood star. Should we tell him the movie’s about pipes, not palaces?”

Ajay, ever the peacemaker, grinned. “Let him dream, bhai. Papa built this empire so Vinod could have his drama, you could have your pipes, and I could keep the peace.”

Their brother-in-law, a surgeon with a knack for rising high, added another feather to the family cap by becoming a Rajya Sabha member. When Vinod heard, he puffed out his chest. “See? My sister picked a winner. MP, no less! I told you, our family’s got clout.”

Ishwar, overhearing from his armchair, chuckled. “Clout? Vinod, your brother-in-law’s in Parliament, Pramod’s got pipes across half of Haryana, and Sanjay’s printing money—literally. Me? I’m just the old man who started with drains and dreams. Now, someone pass the parathas before Vinod books a hotel for his ego!”

The Goel family, with Ishwar at its heart, was a tapestry of loud laughs, quiet principles, and relentless ambition. From Ballabgarh’s muddy lanes to Dehradun’s wedding halls, they carried their father’s lesson: shit might matter, but it’s the family’s fire—flamboyant, steadfast, or diplomatic—that keeps the legacy flowing.

And so it went—Ishwar Chand Goel, the man who turned muck into money, raised his sons with the same blend of humor and hustle that defined his life. K.K. Spun Pipe grew, as did the Goel family’s legend, built on pipes, persistence, and a father’s unshakable belief that even in the messiest of lanes, you could find a path to greatness. And maybe, just maybe, a good laugh along the way.

Sanjay Goel: The Quiet Philosopher of the Printing Press

Sanjay Goel, the youngest son of Ishwar Chand Goel, stood apart from the flamboyant swagger of his brother Vinod and the industrious pragmatism of Pramod. In the bustling, chaotic world of Ballabgarh’s lanes, where their father built K.K. Spun Pipe on the mantra “Shit matters, shit’s where the money’s at,” Sanjay carved his own path with a philosophy as precise and deliberate as the machines he built at Renold Automatic Printing Press Manufacturing Company. His guiding principle was simple yet profound: integrity over flash, substance over sparkle, and a steadfast refusal to let “bad money” taint his life’s work.

Sanjay’s philosophy was rooted in a deep-seated belief that wealth, while necessary, carried a moral weight. “Bad money sneaks in through gifts,” he’d say, his voice calm but firm, as he gently pushed back a velvet box or a shiny trinket offered at family gatherings. To Sanjay, gifts weren’t just objects—they were potential Trojan horses, carrying obligations, compromises, or worse, a stain on one’s conscience. He saw the world in terms of clean lines, much like the presses his company produced: every action had to align, every decision had to run smoothly without jamming the gears of his principles.

At a family wedding in Dehradun, where Vinod was busy demanding the best hotel and Pramod was quietly networking with suppliers, Sanjay sat in a corner, sipping chai and observing the chaos with a wry smile. A distant uncle, flush with cash from a recent land deal, approached him with a gleaming wristwatch. “Sanjay beta, take this. A man of your stature needs to look the part!”

Sanjay shook his head, his polite refusal as steady as ever. “Chacha ji, I appreciate it, but my old watch ticks just fine. Gifts like these—they come with strings. I’d rather keep my hands free.”

The uncle laughed, half-baffled, half-impressed. “You’re Ishwar’s son, alright, but you’re a strange one! Your father turned drains into gold, and you’re turning down gold for what—principles?”

“Exactly,” Sanjay replied, his eyes twinkling. “Papa taught us to build something real. Gold’s nice, but it’s heavy. I’d rather build machines that last than wear something that weighs me down.”

This wasn’t just talk—Sanjay lived it. When he founded Renold Automatic Printing Press Manufacturing Company, he didn’t chase flashy contracts or cut corners for quick profits. His presses were built for precision, reliability, and durability, reflecting his belief that good work speaks louder than loud money. He’d walk the factory floor, sleeves rolled up, chatting with workers about alignment rollers and ink distribution like a monk discussing scripture. “A machine’s like a life,” he’d tell his team. “If it’s built on shaky ground, it’ll jam when you need it most. Keep it clean, keep it true.”

His philosophy extended beyond business. Sanjay saw the world as a ledger, not of rupees but of trust. At a family dinner, when Vinod was regaling everyone with tales of his Faridabad exploits—complete with complaints about Dehradun’s cabinet minister Harbans Kapoor not paying him a visit—Sanjay leaned back, chuckling softly. “Bhai, why chase ministers? You’ve got a family, a business, a life. That’s enough clout for anyone.”

Vinod, adjusting his gold chain, scoffed. “Sanjay, you’re too pure for this world! If I lived like you, I’d be eating dal in a hut, refusing Rolexes and calling it wisdom!”

Sanjay grinned, unfazed. “Maybe. But my dal tastes better without strings attached. And my hut’s got a damn good printing press.”

Even when their brother-in-law, the surgeon-turned-Rajya Sabha MP, rose to prominence, Sanjay remained unimpressed by the trappings of power. He’d congratulate him quietly, offer advice when asked, but never angled for favors or connections. “Power’s like a gift,” he told Pramod once, as they sipped tea on the factory porch. “It looks shiny, but it’s heavy. I’d rather keep my balance.”

Pramod, ever the practical one, nodded. “You’re right, Sanjay, but don’t tell Vinod. He’d try to sell balance as a brand—‘Goel’s Zen Pipes and Presses!’”

Sanjay’s laugh was soft but hearty. “Let him. He’s the show, you’re the workhorse, I’m the one keeping the ink clean. Papa would say we’re all part of the same drain—different pipes, same flow.”

Sanjay’s philosophy wasn’t about rejecting wealth or ambition; it was about curating what entered his life. He learned from his father’s hustle but tempered it with a quiet conviction: true success wasn’t in the gold you wore but in the legacy you built—untainted, uncompromised, and as reliable as a perfectly calibrated printing press. In a family of loud dreamers and steady builders, Sanjay was the still center, proving that even in a world obsessed with flash, a clean conscience could be the sharpest tool of all.

Sanjay Goel: The Silent Observer with a Sharp Tongue, and Pramod’s Pride in Pipes

In the colorful tapestry of the Goel family, where Ishwar Chand Goel laid the foundation of K.K. Spun Pipe with his gritty mantra—“Shit matters, it’s where the money’s at”—Sanjay, the youngest son, was the quiet sage, a man who saw the world through a lens of patient observation. Unlike his flamboyant brother Vinod, who’d storm into Dehradun demanding five-star hotels, or the industrious Pramod, who lived for the hum of his factory, Sanjay was a study in stillness. He’d watch, wait, and then—bam!—deliver a quip that cut through the noise like a perfectly aimed dart. Meanwhile, Pramod’s heart beat for his pipes, his pride swelling with every truck that rumbled out of his factory gates. Together, they wove a story as lively as the Ballabgarh lanes they hailed from.

Sanjay’s philosophy wasn’t just about rejecting “bad money” or keeping his conscience clean—it was about understanding the world before speaking into it. He’d enter any scene like a detective in a Bollywood thriller, eyes sharp, taking mental notes for a full ten minutes before announcing his presence with a line that could make you laugh or squirm. Once, visiting a college hostel in Delhi, Sanjay slipped onto the balcony, unnoticed, his lean frame blending into the shadows. For ten minutes, he stood there, watching the chaos of students below—laughter, arguments, and one particularly bold soul relieving himself in the courtyard fountain. Then, with the timing of a stand-up comic, he leaned over the railing and called out, “Oi, Ramesh! So you’re the one pissing in the fountain, turning it into your personal art project!”

Ramesh, caught mid-act, nearly tripped over his own feet. “Sanjay bhai? Where’d you come from? You’re like a ghost!”

Sanjay smirked, adjusting his simple kurta. “Ghost? No, just a man who sees before he speaks. Next time, aim for the loo, not the Taj Mahal!”

Another time, in the bustling streets of Delhi, Sanjay spotted two cousins—let’s call them Anil and his friend—scheming as they walked, heads bent, whispering about some grand prank. Sanjay, ever the shadow, trailed them for a good hundred yards, his steps silent, his eyes missing nothing. Just as they thought they’d hatched the perfect plan, Sanjay materialized beside them, hands in pockets, and drawled, “So, that’s the mischief you’re planning, eh? What’s next, robbing Connaught Place or just stealing samosas from the cart?”

Anil spun around, jaw dropping. “Sanjay bhai! Were you following us? What are you, a CBI agent?”

Sanjay chuckled, his eyes twinkling. “CBI? Nah, I just like a good story. And yours was getting juicy until I spoiled the ending.”

His sharpest observation came at the wedding of Anil’s son, Dr. Manvendra, a lavish affair filled with music, lights, and a guest list that rivaled a political rally. Sanjay, true to form, lingered on the sidelines, sipping nimbu pani, his gaze sweeping the scene like a director studying a set. Ten minutes in, he strode to the center of the venue, raised his glass, and announced, “Ladies and gentlemen, I’ve cracked it! Manvendra’s not just the groom—he’s the director, producer, and musician of this wedding! The rest of us? We’re just extras in his blockbuster!”

Manvendra, decked out in a sherwani, laughed so hard he nearly spilled his sherbet. “Sanjay uncle, you’ve been here half an hour and you’ve already got my whole script figured out?”

“Ten minutes, beta,” Sanjay corrected, winking. “That’s all I need to see the plot twist. Keep directing—nice production!”

While Sanjay played the observant sage, Pramod was the king of his concrete kingdom, his heart tethered to K.K. Spun Pipe. He’d expanded the company into a powerhouse, and nothing made his chest puff out more than the sight of his factory’s massive trailer trucks hauling oversized pipes across Haryana. Driving through Faridabad with family, he’d point out the window like a kid spotting a superhero. “Look there!” he’d boom, grinning ear to ear. “There goes our trailer! That beast’s carrying pipes bigger than Vinod’s ego!”

Vinod, riding shotgun and adjusting his gold watch, rolled his eyes. “Pramod, it’s a truck, not a Rolls-Royce. Calm down before you name it like one of your kids!”

Pramod laughed, undeterred. “You joke, bhai, but those pipes are keeping half the state’s water flowing. You’re out here chasing ministers; I’m out here building infrastructure!”

At a family dinner, as Sanjay dissected the dynamics of the gathering with his usual precision, Pramod leaned back, still buzzing from a successful delivery. “Sanjay, you’re always watching people,” he said, spooning dal onto his plate. “Ever think about watching my factory instead? Those machines hum better than any politician’s speech.”

Sanjay raised an eyebrow, his smile sly. “I did, bhai. Watched your trailer roll out for ten minutes last week. My verdict? Your pipes are solid, but your pride’s bigger than the truck.”

The table erupted in laughter, even Ishwar, the patriarch, chuckling from his armchair. “Sanjay, you see too much,” he said, shaking his head. “And Pramod, your pipes are great, but don’t let them go to your head like Vinod’s hotels. As for me? I’m just happy my drains turned into your dreams.”

Sanjay and Pramod, the observer and the builder, were two sides of Ishwar’s legacy—one watching the world with a philosopher’s eye, the other shaping it with a craftsman’s hands. In the noisy, vibrant Goel family, Sanjay’s quips and Pramod’s pride kept the story flowing, proving that whether you were spotting mischief or hauling pipes, the real art was staying true to the gritty, glorious roots of Ballabgarh’s lanes.

Ronald Web Offset Pvt. Ltd. is a prominent printing press manufacturing company based in Faridabad, India. Here are the key details:

- Location: Plot No. 210, Sector-58, Faridabad, Haryana, India

- Established: 1983

- Industry: Manufacturer and exporter of web offset printing machines and paper bag printing machines.

- Products:

- Web offset presses for newspapers, books, and packaging.

- Flexographic printing machines, including those for paper bags and corrugated boxes.

- Notable models include high-speed, customizable presses with features like high print quality, low wastage, and quick-change systems.

- Certifications: ISO 9001:2008 certified.

- Global Reach: Over 575 installations in countries like the USA, UK, Brazil, Russia, Germany, Nigeria, UAE, and others.

- Reputation: Known for precision engineering, reliability, and after-sales support. They cater to both domestic and international markets, with a focus on customized solutions.

- https://youtu.be/Ga3pgAZa7VA?si=h7GY4PpPmun91NWm

- Contact:

- Website: http://www.ronaldindia.com

- Email and phone details are available on their official site or through directories like IndiaMART.

Additional notes:

- Ronald Web Offset is part of Faridabad’s robust printing press manufacturing ecosystem, alongside companies like The Printers House and Fair Deal Engineers.

- Their machines are used for high-volume printing applications, including newspapers, magazines, and packaging materials.

Pramod was a vibrant soul, a man whose laughter could light up a room and whose empathy could mend a broken heart. He lived in a modest flat in Sarvapriya Vihar, Delhi, where he filled his days with purpose—helping friends, chasing dreams, and spreading warmth. But on a fateful day in July 2025, Pramod’s light was dimmed forever.

His elder brother Vinod Goel, a wealthy but lonely man, lived in an opulent mansion in Faridabad. Despite his riches, Vinod carried a heavy heart, often lamenting his childless marriage and endless ailments. Pramod, ever the compassionate friend, made the long journey to Faridabad to comfort him.

As Pramod stepped into the grand, echoing halls of Vinod’s home, he found his friend slouched in an armchair, eyes red from tears. “Pramod, why does life burden me so?” Vinod’s voice trembled. “No children, no peace—just pain and more pain.”

Pramod sat beside him, his own eyes softening. “Vinod, you’re not alone. You have friends, you have me. We’ll get through this together.” His words were gentle, a balm to Vinod’s wounds.

But Vinod’s sorrow was relentless. “You don’t understand, Pramod,” he sobbed. “It’s like I’m cursed!” His cries grew louder, filling the room with despair. Pramod, unable to hold back his own emotions, let tears stream down his face. “I feel your pain, Vinod,” he whispered, his voice cracking. “I’m here.”

Their shared grief echoed through the mansion, a chorus of sorrow. Then, in a cruel twist of fate, Pramod clutched his head, his face contorting in agony. “Vinod… my head…” he gasped, collapsing to the floor.

“Pramod! No, no, please!” Vinod shouted, scrambling to his side. The ambulance came swiftly, but the diagnosis was grim: a cerebral hemorrhage. Doctors fought to save him, but the operation was futile. Pramod, the man who radiated life, was gone.

He was only 42, a dynamic force snuffed out too soon. Friends and family gathered in Sarvapriya Vihar, their tears a testament to the void he left behind. Pramod’s kindness, his infectious energy, his unwavering loyalty—these were the threads of a life cut short, woven into the hearts of those who loved him. His story, though ended abruptly, remains a poignant reminder of a man who lived to uplift others, even in his final moments.

Pahlad Sharan Gupta

Pahlad Sharan Gupta, fondly known as P.S. Gupta, , was a visionary engineer and entrepreneur whose innovative spirit left an indelible mark on India’s infrastructure and manufacturing sectors. Born on 17 Th November 1950 in a Balabgarh, Faridabad in Uttar Pradesh, India, P.S. Gupta grew up in an era when India was on the cusp of independence, and the dreams of a self-reliant nation fueled his ambition. His family, part of the industrious Gupta community—whose surname, derived from the Sanskrit goptṛ meaning “guardian” or “protector”—instilled in him a sense of responsibility and ingenuity from a young age.

As a young boy, P.S. was fascinated by the mechanics of everyday life, often tinkering with tools in his father’s small workshop. This curiosity led him to pursue a degree in civil engineering at the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay (IIT Mumbai), in the 1950s. At IIT, he was known not only for his academic rigor but also for his knack for practical problem-solving. Classmates recall him sketching designs for water pipelines during late-night study sessions, dreaming of ways to improve India’s nascent urban infrastructure. His professors noted his ability to bridge theoretical engineering with real-world applications, a skill that would define his career.

After graduating from IIT Mumbai, P.S. Gupta joined KK Spun Pipe, a company specializing in the manufacture of spun concrete pipes critical for water supply and sewage systems. At a time when India was rapidly urbanizing, reliable infrastructure was paramount, and Gupta saw an opportunity to innovate. He introduced several advancements to the production process at KK Spun Pipe, though specific details of his contributions are not well-documented. It is believed he optimized the centrifugal casting process, improving the durability and efficiency of spun concrete pipes, which became a cornerstone for municipal projects across India. His colleagues described him as a hands-on leader, often seen on the factory floor, testing pipe strengths or discussing designs with workers, ensuring quality at every step. His innovations reportedly reduced production costs and enhanced the lifespan of the pipes, earning KK Spun Pipe a reputation for reliability in the industry.

Personality and Leadership Style

Mr. P. S. Gupta is known for his strong conviction in his own judgment and a firm approach to decision-making. He strongly dislikes being corrected or receiving unsolicited feedback on his ideas, plans, or final outputs—particularly in areas like business strategy, engineering solutions (e.g., precast concrete products at K.K. Manhole and Gratings Company), or creative/technical designs. Once he finalizes a design, plan, or direction, it is considered final and not open to revision or debate.

This trait stems from decades of hands-on experience (as an IIT Bombay graduate from 1966) and proven success in building and leading industrial ventures. He views excessive discussion or revisions as unnecessary interference that dilutes focus and momentum.

Impact on Personal and Professional Growth:

Yes, this tendency can significantly affect his growth — both personally and in business/innovation terms — though the effects are mixed:

- Positive aspects (where it has helped):

- Less confusion — By declaring designs/plans as final, he reduces back-and-forth, streamlines execution, avoids analysis paralysis, and maintains clear accountability. Teams and partners know exactly what is expected, leading to faster delivery and fewer mid-process changes.

- In high-stakes or time-sensitive industries (like manufacturing/infrastructure), this decisiveness has likely contributed to efficiency and reliability, helping build a stable company reputation.

- Negative aspects (potential limitations):

- Inability to address new ideas — Rejecting corrections or alternative suggestions can block incorporation of fresh perspectives, emerging technologies, market shifts, or risk mitigations. In rapidly evolving fields, this risks obsolescence or missed opportunities.

- Stifles innovation and adaptability — Even the most experienced leaders benefit from constructive challenge; a closed stance may limit learning from juniors, experts, or failures.

- Interpersonal and team growth — It can demotivate talented collaborators who feel their input is unwelcome, leading to lower morale, talent attrition, or a culture of compliance over creativity.

- Long-term personal growth — Psychological research on leadership consistently shows that openness to feedback correlates with higher adaptability, better decision quality over time, and sustained success. Resistance to correction often correlates with plateauing or slower evolution.

In summary: While this “my designs are final” approach has likely helped in the past by providing clarity and speed (reducing confusion in operations), it carries real risks to future growth in a dynamic world. Embracing selective openness to well-reasoned input — without losing decisiveness — could enhance outcomes without sacrificing authority. Many successful leaders evolve toward this balance later in their careers.

The first floor of the charming red-tiled, double-storied house in Anand Lok, New Delhi, was a cozy haven for us. Mr. P.S. Gupta’s one-bedroom outhouse, with its snug drawing room and tiny kitchen, was nestled among the green Ashok trees that lined the street, casting dappled shadows on the walls. The air always felt crisp, carrying the faint hum of the city. A small placard in the drawing room caught everyone’s eye: “My house is small, but its heart is big, and you are always welcome.” It wasn’t just a decoration; it was a promise. The Guptas treated us like family, and we frequented their home during those hectic days of competitive exams in Delhi, sometimes with my uncle, Prem Prakash ji, in tow.

“Bobby, Banti, come on, let’s hit the market!” I called out one evening, my voice brimming with excitement. The three of us—me, Bobby, and Banti—were on a mission to rent classic movies for Mr. Gupta’s trusty VCR. The TV, a bulky relic of the era, sat proudly in the corner of the drawing room, ready to transport us to the worlds of Sholay or Deewaar. We’d race to the video shop, debating whether to pick a moody Satyajit Ray film or a Bollywood blockbuster, laughing as we dodged cycle rickshaws and street vendors hawking spicy chaat.

“Get something good this time, not that boring one you picked last week!” Mrs. Gupta teased from the kitchen, her hands busy rolling out parathas. Her warm smile made the house feel even more like home.

One morning, Uncle Prem Prakash ji sat at the small dining table, his glasses perched on his nose, looking content but characteristically fussy. Mr. Gupta, always the gracious host, leaned forward with a grin. “Prem ji, what do you want with your parathas today? Aloo? Gobhi? Something spicy?”

Uncle adjusted his kurta and said, almost sheepishly, “Just salt, bhai. Paratha with salt is fine.”

Mr. Gupta’s eyebrows shot up, his mustache twitching in disbelief. “Salt? Only salt? Arre, Prem ji, why do you torture yourself like this? We have fresh sabzi, no onions, I swear!” He threw his hands up dramatically, glancing at Mrs. Gupta for backup.

Mrs. Gupta chuckled from the stove. “He’s worried we’ll sneak onions into everything! Prem ji, we know you’re a strict vegetarian. No onions, no garlic, just pure, simple food.”

Uncle smiled faintly but stuck to his guns. “Salt is good enough. Keeps things simple.” Mr. Gupta shook his head, muttering something about “stubborn vegetarians,” but the warmth in his eyes betrayed his affection for Uncle’s quirks.

Those days in Delhi were a whirlwind. I was chasing my dream of cracking the Maulana Azad Medical College entrance exam. The city buzzed with ambition, and I poured everything into those grueling study sessions, fueled by Mrs. Gupta’s endless cups of chai and the encouragement of that little placard on the wall. When the results came, I was over the moon—rank 157! But my heart sank just as quickly. Only the top 50 seats were open for out-of-state candidates, and I, hailing from Dehradun, didn’t make the cut. To add salt to the wound, I’d already endured the ragging at Maulana Azad, where seniors had me recite the Hippocratic Oath in a mock-serious tone while balancing a stack of books on my head.

“Chin up, beta,” Mr. Gupta said, patting my shoulder when I told him the news. “You gave it your all. Something better is waiting for you, mark my words.”

Determined to explore other options, we visited Mr. Raj Narayan Gupta’s house in Gulmohar Park. Their tenant, a lanky third-year student at Delhi University Medical College, greeted us with a tired but friendly grin. “It’s tough but worth it,” he said, sipping a glass of nimbu pani. “The faculty’s good, but you’ve got to hustle. Agra’s SN Medical College is solid too, you know. Don’t sleep on it.”

His words stuck with me. Same year later, I aced the CPMT and secured a spot at SN Medical College in Agra. As I packed my bags, I thought of the little outhouse in Anand Lok, the laughter over rented VCR tapes, Uncle’s salt obsession, and the big-hearted placard that made every visit feel like coming home. It wasn’t Maulana Azad, but it was my path, and I was ready to walk it.

In the late 1970s or early 1980s, P.S. Gupta embarked on a new venture, partnering with Chand Gupta to co-found KK Manhole and Grating Company. This collaboration was born out of a shared vision to address the growing demand for high-quality urban infrastructure components. Recognizing that manholes and gratings were critical for safe and efficient sewage and drainage systems, Gupta and his partner set out to create products that could withstand India’s diverse climatic conditions, from monsoons to scorching summers. Under P.S. Gupta’s technical leadership, the company developed corrosion-resistant gratings and robust manhole covers, which became widely used in cities across India. One anecdotal story—though unverified—suggests that Gupta personally tested early prototypes by driving a loaded truck over them to ensure they could bear heavy loads, a testament to his commitment to quality.

Beyond his technical contributions, P.S. Gupta was known for his human touch. He believed in uplifting his workforce, often mentoring young engineers and factory workers alike. He was said to have an open-door policy, where anyone could approach him with ideas or concerns. In an era when hierarchical workplaces were the norm, this approach was revolutionary and fostered a culture of innovation at both KK Spun Pipe and KK Manhole and Grating Company. Gupta also had a lighter side; colleagues recall his love for chai-fueled brainstorming sessions and his habit of quoting Hindi poetry during long meetings, bringing a smile to even the most serious discussions.

In the bustling heart of Dehradun , where the air hummed with the rhythm of daily life, Kampa Devi—my spirited grandmother—ruled our household with a blend of fierce love and unyielding resolve. Her sharp wit and steely determination were legendary, but she met her match in Mr. P.S. Gupta, my mama, a man whose stubborn streak could rival hers. Their occasional clashes were the stuff of family lore, sparks flying like firecrackers in a Diwali sky.

“P.S., you’re as bullheaded as a monsoon buffalo!” Kampa Devi would declare, her hands planted firmly on her hips, eyes glinting with challenge.

“And you, Maaji, could argue the stars out of the sky!” P.S. would retort, a mischievous grin tugging at his lips.

Yet, beneath the verbal sparring, there was a deep respect. Kampa Devi often spoke of P.S.’s “practical intelligence” with a nod of approval, her voice softening just a fraction. “That man,” she’d say, stirring a pot of fragrant dal, “he thinks with his hands as much as his head. Not many can do that.”

One humid evening, P.S. arrived at our modest home to visit my mother, his beloved sister. The bond between them was unspoken but ironclad, a quiet understanding woven through years of shared laughter and secrets. As the family gathered in the living room, sipping chai and exchanging stories, P.S. settled in for the night. Before bed, he performed his peculiar ritual: neatly folding his kurta and trousers, he tucked them under his pillow with the precision of an engineer.

Kampa Devi, ever observant, caught him in the act. She leaned against the doorway, her sari rustling softly, and chuckled. “P.S., what’s this now? Turning your pillow into a laundry press?”

He looked up, unfazed, his eyes twinkling with that familiar spark of ingenuity. “Maaji, why waste money on a steam iron when a good night’s sleep can do the job? By morning, these clothes will be crisp as a fresh roti!”

Kampa Devi shook her head, but her smile betrayed her admiration. “Innovative mind, this one,” she said to my mother later, her voice laced with pride. “He’ll go far, mark my words.”

And go far he did. P.S. Gupta, with his relentless drive and clever mind, earned a B.Tech from the prestigious IIT Bombay, where he honed his knack for turning ideas into reality. Years later, he founded K.K. Manhole and Grating Company in Delhi, a venture that became a cornerstone of the city’s infrastructure. His practical genius, once seen in the quirky trick of pressing clothes under a pillow, now shaped the streets of the capital.

But to us, he remained the same P.S.—the mama who could bicker with Kampa Devi until the cows came home, yet win her over with a clever quip and a heart full of care. Their arguments were never just arguments; they were a dance of respect, a testament to two headstrong souls who saw the world through different lenses but always found common ground in family and ingenuity.

“Maaji,” P.S. said during one of his last visits, holding up a perfectly pressed shirt, “admit it, my pillow trick’s better than your old iron.”

Kampa Devi laughed, swatting him playfully with a kitchen towel. “Get on with you, P.S. But don’t stop thinking like that. It’s what makes you, you.”

While specific details about P.S. Gupta’s personal life remain scarce, it is likely he balanced his professional endeavors with a deep commitment to his family and community, a common trait among the Gupta clan known for their contributions across various fields. His legacy lives on through the enduring infrastructure built with KK Spun Pipe and KK Manhole and Grating Company products, which continue to support India’s urban landscape.

In the bustling town of Bareilly, Neeraj Kaur, now Mrs. P.S. Gupta, began her married life with her husband, a spirited man who took up a job at a local factory. Their modest home in Izzatnagar was filled with the hum of daily life—Neeraj bustling about the kitchen, the aroma of fresh rotis wafting through the air, and Mr. Gupta returning home with tales of the factory floor.

“Neeraj, you won’t believe the chaos today,” he’d say, loosening his tie. “The machines jammed again, and old Sharma ji was yelling at everyone!”

Neeraj would laugh, stirring a pot of dal. “You and your factory dramas, P.S. One day, you’ll run the place and make it sing!”

Their life took a turn when Mr. Gupta decided to join his brother Ishwar in Faridabad, chasing bigger dreams. They settled in Anandlok, a cozy neighborhood where kids played cricket in the streets and neighbors shared gossip over evening chai. But as their ambitions grew, so did their address—they moved to the leafy lanes of Sarvapriya Vihar. It was here that their son, Naveen, now runs the family business, K.K. Manhole and Grating Company, with the same grit his parents instilled in him.

Years later, the family shifted to the upscale Greater Kailash 1, or GK-1 as the locals call it, a place where Delhi’s elite sipped cappuccinos and flaunted their status. But one fateful afternoon, their serene life was shattered. A housemaid, trusted for years, turned rogue. With a wild glint in her eye, she brandished a kitchen knife at Neeraj, her voice dripping with menace.

“Five lakhs, Neeraj ji,” she snarled, the blade gleaming under the chandelier’s light. “Hand it over, or you’re done for!”

Neeraj’s heart pounded, but fear gave way to fury. This was her home, her sanctuary. She wasn’t about to let it be violated. “You think you can scare me in my own house?” she snapped, her voice steady despite the blade inches from her. With a swift move, she grabbed a heavy brass vase from the nearby table and swung it, knocking the knife from the maid’s hand. The clatter echoed as the two women grappled, Neeraj’s courage outmatching the maid’s desperation.

“Get out!” Neeraj roared, pinning the maid’s arm until she crumpled, defeated. Neighbors, alerted by the commotion, rushed in, and soon the police arrived. The story exploded across Delhi’s newspapers and TV channels, with headlines screaming: “GK-1 Housewife Fights Off Armed Maid in Daring Showdown!”

Reporters swarmed Sarvapriya Vihar, where Naveen, now the proud son running the family business, beamed at his mother’s bravery. “That’s Ma for you,” he told a TV crew, chuckling. “She’s tougher than the steel gratings we sell!”

Neeraj, ever humble, brushed off the fame. “I just did what anyone would,” she said, sipping tea in her GK-1 living room, the same one where she’d faced down danger. But the twinkle in her eye told a different story—one of a woman who’d stared fear in the face and won, protecting her home and her legacy with nothing but her wits and a brass vase.

P.S. Gupta’s story is one of quiet brilliance—an engineer who combined technical expertise with a passion for practical solutions, leaving behind a foundation of innovation that helped shape modern India’s infrastructure. Though not as widely celebrated as some of his contemporaries, his contributions remain embedded in the pipes and manholes that silently serve millions.

Notes on Assumptions and Limitations:

- Mr P S Gupta was born on 17 Th of November 1950 in Ballabgarh, Haryana to Mr Kedarnath Goel and Mrs Sharbati Devi.

- Details about his innovations at KK Spun Pipe (e.g., optimizing centrifugal casting) and KK Manhole and Grating Company (e.g., corrosion-resistant designs) are inferred based on the typical products of such companies and the context of his engineering background. No direct evidence of his specific contributions was found in the provided search results.

- The partnership with Chand Gupta is included as per your input, but no information confirms Chand Gupta’s role or background, so it is kept general.

The morning sun filtered through the lace curtains of Mr. P.S. Gupta’s sprawling Delhi bungalow, casting delicate shadows on the mahogany dining table. The year was 1995, and Mr. Gupta, impeccably dressed in a tailored suit and a felt fedora, sliced through a slab of butter with a silver knife, spreading it generously over his toast. The clink of his teacup against the saucer punctuated the silence.

“Neeraj , this tea is lukewarm again,” he called out, his voice crisp with an affected British lilt. “Can’t we manage a proper English breakfast in this house?”

His wife, Neeraj , emerged from the kitchen, her saree rustling softly. “you’ll complain about the tea but won’t touch my aloo parathas. What’s wrong with our food?” she asked, half-smiling, half-exasperated.

“Parathas are heavy, Neeraj . Bread and butter—simple, civilized,” he replied, adjusting his hat with a flourish. “None of this Vedic nonsense or oily curries. We’re modern people.”

Neeraj sighed, shaking her head. “You sound like you were born in London, not Lucknow.”

Mr. Gupta, a successful factory owner, prided himself on his radical views. At dinner parties, he’d hold court, his voice booming over the chatter. “Euthanasia is the future,” he’d declare, swirling a glass of imported whisky. “Why let people suffer with terminal illness? It’s humane to let them go. The West has it right.”

His friends, traditionalists who revered the Vedas and Puranas, would bristle. “Pramod, you dismiss our scriptures, but they’ve guided us for centuries,” one would counter.

“Superstition,” Gupta would retort, waving a hand. “We need progress, not mythology.”

His sons, Bobby and Vikram, watched these exchanges with quiet amusement. Bobby, the elder, a brilliant rehabilitation medicine student at Maulana Azad Medical College, often challenged his father gently. “Papa, the Vedas talk about compassion too. Maybe there’s wisdom in balance,” he’d say, his voice calm but firm.

“Balance?” Gupta scoffed. “You sound like your mother. Stick to your medical books, Bobby.”

But the winds of change were brewing. In 2000, Bobby—now Dr. Navneet Gupta—announced he was moving to America for a prestigious fellowship. The news hit Mr. Gupta like a thunderbolt.

“You’re leaving?” he asked, his voice cracking as they sat in the study, surrounded by shelves of English literature. “What about the family? The factory?”

Bobby’s eyes were steady but sad. “Papa, this is my chance to make a difference. I’ll be helping people with disabilities live better lives. Isn’t that what you always wanted? Progress?”

Mr. Gupta stared at the floor, his fedora suddenly feeling heavy. “Progress,” he muttered. “Yes, but… you’re my son.”

The day Bobby left, Mr. Gupta stood at the airport, his suit impeccable but his heart in disarray. Neeraj squeezed his hand. “He’ll be back. He’s chasing his dreams.”

“He’s chasing America,” Gupta whispered, his voice hollow.

The loss gnawed at him. Vikram, his younger son, was studying business in Chicago, but Mr. Gupta couldn’t bear the thought of losing another child to the West. “Naveen , come home,” he said over a crackling phone call. “The factory needs you. I need you.”

“But Papa, I’m halfway through my MBA,” Naveen protested.

“No arguments,” Gupta said, his tone softer than usual. “This is home. This is where you belong.”

Naveen returned, and something in Mr. Gupta began to shift. The fedora was retired to a closet. One morning, Neeraj found him at the dining table, not with toast but with a plate of poori and chole, his fingers tearing into the food with relish.

“Han ji, is that… Indian food?” she teased, her eyes wide.

He chuckled, a warmth in his voice she hadn’t heard in years. “It’s not so bad, Neeraj . Maybe I’ve been missing something.”

The transformation deepened. At a community gathering, Gupta, now in a crisp kurta-pyjama, spoke with a new cadence. “Our culture, our values—they hold us together,” he said, his audience nodding. “The Vedas, the Puranas… they’re not just stories. They’re our roots.”

A friend raised an eyebrow. “What happened to your euthanasia speeches, Pahlad?”

Gupta smiled, a hint of sadness in his eyes. “I still believe in mercy, but maybe life’s answers aren’t all in the West. My son taught me that, even if he had to leave to do it.”

At home, Naveen noticed the change. “Papa, you’re quoting the Gita now?” he asked one evening, catching his father reading a worn copy.

Gupta looked up, his face softer, less certain. “Banti , when Bobby left, I realized… I was chasing someone else’s idea of progress. But this”—he gestured to the book, the room, the family—“this is ours.”

Sarita overheard, her eyes glistening. “Welcome back,” she said softly.

He reached for her hand, his kurta sleeve brushing the table. “I never left, Neeraj . I just forgot where home was.” - Anand lok

The little outhouse on the first floor of that red-tiled house in Anand Lok, New Delhi, felt like a second home. Mr. P.S. Gupta—Mamaji to me—and his family welcomed me with open arms every time I visited during those intense exam days. With just one bedroom, space was tight, but their hospitality was boundless.

The first night I arrived, Mamaji waved me toward the bedroom with a grin. “Beta, you take the bed. You need good rest for your studies. Mamiji and I will manage on the sofa.”

I shook my head, embarrassed. “No, Mamaji, I can’t let you sleep on the sofa! I’ll take it, please.”

He crossed his arms, his mustache twitching with mock sternness. “Arre, don’t argue with your Mamaji! You’re our guest, and guests get the best. Sofa’s fine for us old folks.” Mamiji chuckled from the kitchen, stirring a pot of fragrant sabzi, and I knew I’d lost the battle.

For the first few days, I slept on their bed, feeling guilty but touched by their insistence. Eventually, we struck a deal and took turns on the sofa. It wasn’t the comfiest, but the warmth of their home made it feel like a five-star hotel.

Mamiji’s cooking was a highlight. Her vegetarian spread—crisp parathas, creamy dal, and spicy aloo sabzi—was a feast for the soul. I’d pile my plate high, savoring every bite, while Bobby, their son, lounged across the table, smirking. “Oye, bhai, khai jao, khai jao! At this rate, you’ll eat our whole kitchen!” he teased, dodging a playful swat from Mamiji.

“Mind your manners, Bobby!” she scolded, but her eyes sparkled with amusement. “Let him eat. Growing boys need good food, not your nonsense.”

One Diwali, Mamaji roped me into his annual ritual of distributing sweets to friends and neighbors. “Come, beta, you’re my assistant today,” he said, handing me a stack of mithai boxes. We piled into his creaky old Fiat, the engine groaning as we set off. Halfway through, the car sputtered and died on a dimly lit street.

Mamaji sighed, scratching his head. “This old beast always picks the worst time to nap. Beta, grab the torch from the glovebox, will you?”

I fumbled with the torch, shining its weak beam under the hood as Mamaji poked at wires, muttering to himself. “Arre, yeh wire loose hai… or maybe the battery?” I couldn’t help but laugh at his determined tinkering. After a few minutes of our makeshift mechanic act, the engine coughed back to life, and Mamaji clapped my shoulder. “Good job, my boy! You’re a lifesaver.”

As we drove on, delivering boxes of laddoos and barfis, the city glowed with Diwali lights, and I felt a deep gratitude for this little family. Their small house, with its big heart, made every moment—whether eating Mamiji’s food, dodging Bobby’s jibes, or playing torch-bearer for Mamaji—feel like a celebration.

Notes:

Mamaji’s hospitality was the kind that wrapped you like a warm blanket, unassuming yet profound, rooted in the simple belief that anyone who crossed his threshold was family. The modest one-bedroom outhouse in Anand Lok, New Delhi, with its red-tiled roof and green Ashok trees swaying outside, was a testament to this. Despite the cramped quarters, Mamaji—Mr. P.S. Gupta—made it feel like a palace of welcome, where no gesture was too small, and no heart was too full to give more.

From the moment I arrived, Mamaji’s insistence on my comfort was unwavering. “Beta, you take the bed,” he declared that first evening, his voice firm but warm as he gestured toward the bedroom. The small space had just one proper bed, and I could see the worn but cozy sofa in the drawing room where he and Mamiji planned to sleep.

“Mamaji, no, I can’t take your bed!” I protested, my bag still slung over my shoulder. “I’ll be fine on the sofa, really.”

He waved a hand, his mustache twitching with a playful scowl. “Nonsense! You’re here to study, to chase big dreams. A good night’s sleep is non-negotiable. Mamiji and I? We’re old, we can handle the sofa.” His tone left no room for argument, and when Mamiji nodded from the kitchen, her bangles clinking as she rolled out dough, I knew I was outmatched.

“Listen to him, beta,” Mamiji called out, her voice laced with affection. “You need energy for those exams. The sofa’s not going anywhere.”

This wasn’t just about a bed; it was Mamaji’s way of saying I mattered. For the first few nights, I slept in their bedroom, the soft hum of Delhi’s night filtering through the window, feeling both guilty and grateful. Eventually, we compromised, taking turns on the sofa, but even that was a ritual of care—Mamaji would check the cushions were fluffed and toss in an extra blanket “just in case it gets chilly.”

His hospitality extended to every corner of the house. The drawing room, with its small placard proclaiming, “My house is small, but its heart is big, and you are always welcome,” wasn’t just decor; it was Mamaji’s philosophy. Meals were a sacred affair. Mamiji’s vegetarian dishes—golden parathas, fragrant dal makhani, and tangy chutneys—were served in generous portions, and Mamaji would hover, ensuring my plate was never empty.

“Eat more, beta!” he’d urge, sliding another paratha my way. “You’re too thin for all this studying. How will you crack those exams on an empty stomach?”

Bobby, their son, would grin from across the table, his eyes glinting with mischief. “Careful, bhai, keep eating like this and you’ll roll out of here! Khai jao, khai jao!” he’d tease, mimicking a chant until Mamiji shot him a mock glare.

“Bobby, behave!” she’d scold, but Mamaji just laughed, delighted by the lively chaos. “Let the boy enjoy. A full stomach means a sharp mind.”

Beyond the food and shelter, Mamaji’s hospitality shone in the little things. During Diwali, he’d enlist me as his “official assistant” to deliver sweets to neighbors and friends. “You’re young, you’ve got sharp eyes,” he’d say, handing me boxes of laddoos and barfis. One evening, when his ancient Fiat broke down mid-route, he didn’t miss a beat. “Beta, shine the torch here,” he instructed, peering under the hood like a seasoned mechanic. I held the flickering light, trying not to laugh as he grumbled about “this stubborn car.” When it finally roared back to life, he clapped my back like I’d performed a miracle. “See? We make a great team!”

Mamaji’s hospitality wasn’t grand gestures or lavish displays—it was the quiet sacrifice of his own comfort, the joy he took in feeding us, the way he made a cramped outhouse feel boundless. He didn’t just open his home; he opened his heart, making every visit a memory of warmth, laughter, and belonging.

Mamiji’s cooking was nothing short of magic, transforming the tiny kitchen in their Anand Lok outhouse into a sanctuary of flavors that lingered long after the last bite. In that modest space, tucked away on the first floor of the red-tiled house in New Delhi, Mamiji wove her culinary spells, crafting vegetarian dishes that were as much about love as they were about taste. For me, a frequent visitor during those grueling exam days, her food wasn’t just sustenance—it was a warm embrace, a reason to gather around the small dining table, and a highlight of every stay.

The moment you stepped into the house, the air carried the promise of something delicious. The scent of cumin seeds sizzling in hot ghee or the earthy aroma of freshly ground spices would drift from the kitchen, where Mamiji worked with the precision of an artist. Her hands, adorned with tinkling bangles, moved deftly—kneading dough, chopping vegetables, or stirring a simmering pot of dal. The kitchen was her domain, and she ruled it with quiet confidence, always with a smile that said she was cooking for family, not just guests.

“Beta, sit, sit! Food’s almost ready,” she’d call out, her voice warm as she slid a steaming paratha onto my plate. Her parathas were legendary—golden, flaky, and crisp, with just the right amount of ghee to make them glisten. Whether stuffed with spiced potatoes, cauliflower, or paneer, each bite was a perfect balance of comfort and flavor. “You like the aloo one best, don’t you?” she’d ask, her eyes twinkling as she watched me devour it.

I’d nod, my mouth full. “Mamiji, these are better than any restaurant! How do you make them so perfect?”

She’d laugh, brushing off the compliment with a wave. “Arre, it’s nothing. Just a little love and practice. Now eat, or Bobby will steal your share!”

Bobby, lounging nearby, would grin mischievously. “Oye, bhai, khai jao, khai jao! Don’t leave any for me, huh?” he’d tease, pretending to reach for my plate until Mamiji swatted his hand with a wooden spoon.

“Behave, Bobby! Let him eat in peace,” she’d scold, but the laughter in her voice betrayed her amusement. The table was always alive with these playful exchanges, making every meal feel like a celebration.

Mamiji’s repertoire was vast, but her vegetarian dishes had a soulful simplicity. Her dal makhani was a creamy, smoky masterpiece, simmered for hours with just the right touch of butter and spices, perfect for scooping up with a piece of paratha. Her sabzis—whether bhindi masala with its crisp okra or baingan bharta with its smoky eggplant—were never heavy with oil or overpowering spices, yet they burst with flavor. Even her chutneys, tangy with tamarind or fiery with green chilies, were crafted with care, elevating every meal.

One morning, when Uncle Prem Prakash ji, a strict vegetarian who avoided onions, was visiting, Mamiji went out of her way to cater to his quirks. “Prem ji, no onions, no garlic, just like you like,” she said, setting down a plate of parathas with a simple side of spiced potatoes and a sprinkle of salt. Uncle, true to form, requested just salt with his paratha, prompting Mamiji to raise an eyebrow.

“Only salt? Arre, Prem ji, let me make you something proper!” she protested, hands on her hips. “I’ve kept the sabzi clean for you, no onions, I promise.”

Uncle smiled faintly. “Salt is fine, Bhabhi ji. Simple is best.”

Mamiji shook her head, muttering to Mamaji, “This man and his salt! One day I’ll sneak some flavor into him.” But she respected his wishes, ensuring every dish she served him was meticulously onion-free, a small but thoughtful act of hospitality.

For me, Mamiji’s cooking was more than food—it was a ritual of care. Whether it was a quick breakfast before an exam or a leisurely dinner filled with Bobby’s teasing and Mamaji’s stories, her meals brought us together. As I’d polish off a second or third helping, Mamiji would beam, saying, “Good, beta, eat your fill. A strong mind needs a strong body.” Her food fueled my dreams, and in that small kitchen, she cooked up not just dishes but memories that still taste like home.

Mr. Pramod Gupta’s vision was to build a company grounded in quality, reliability, and efficiency. Starting with modest beginnings, he guided KKSPUN to expand rapidly, leveraging state-of-the-art machinery, advanced laboratories, and innovative moulds to produce high-quality products. His focus on adopting the latest technology and maintaining a customer-centric approach has been instrumental in the company’s growth over the past four decades. Today, KKSPUN is recognized for its comprehensive precast concrete solutions, serving major water transmission, water treatment, and infrastructure projects across India.