Dr. Krishna Chandra Dube (1926–1989) wasn’t just a psychiatrist—he was a revolutionary who turned the dusty wards of Agra’s Mental Hospital into a beacon of hope and progress for mental health care in India. Picture a man with a sharp mind, a warm smile, and an unyielding drive to change how society viewed mental illness. His story is one of courage, curiosity, and a knack for challenging the status quo.

A Young Doctor with Big Dreams

A Cherished Encounter: Dr. P.K. Gupta Remembers Dr. K.C. Dube

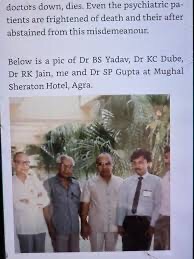

In the opulent corridors of the Mughal Sheraton Hotel in Agra, during the inaugural International Conference of the SAARC Psychiatric Federation from December 2-4, 2005, I, Dr. P.K. Gupta, had the profound privilege of meeting Dr. Krishna Chandra Dube—a legendary pioneer in Indian psychiatry whose seminal 1961 Agra community survey revolutionized epidemiological approaches to mental health in the developing world. At 92, Dr. Dube was a living testament to dedication, having served on the WHO’s Expert Advisory Panel on Mental Health and authored over 100 influential papers. The conference buzzed with South Asian experts exchanging ideas on regional mental health challenges, but amidst the scholarly intensity, Dr. Dube’s presence was like a calming anchor, his wisdom drawing admirers like moths to a flame.

I caught sight of him in the lobby, his frail yet dignified frame illuminated by the hotel’s crystal chandeliers, chatting animatedly with a cluster of colleagues. As a young psychiatrist fresh from my residency at S.N. Medical College in Agra, I had long revered his work—his studies had inspired my own path in neuropsychiatry and epileptology. Mustering my courage, I approached, my pulse quickening. “Dr. Dube,” I said, shaking his hand with reverence, “Your Agra survey changed how we understand mental health in communities. It’s an honor to meet you. Would you allow me a photograph? It would be a treasured memento.”

His face lit up with a kind, knowing smile, his eyes sparkling with the vitality that belied his age. Far from the aloof icon one might expect, he radiated genuine warmth, like a wise grandfather eager to connect. “Absolutely, young man!” he responded in his gentle, deliberate tone, with a soft chuckle. “But let’s not make it solitary—photographs are better with friends. Rakesh! Balwant! Join us here!”

He summoned Dr. R.K. Jain, a fellow psychiatrist and my former mentor at S.N. Medical College, who had penned Dr. Dube’s heartfelt obituary later that year, and Dr. B.S. Yadav, a dedicated collaborator from Agra’s Institute of Mental Health and Hospital, who had served as co-investigator on Dr. Dube’s groundbreaking International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. Dr. Jain strode over, flashing a wry grin as he straightened his collar. “Krishna, always turning moments into memories! What’s the fuss—a new award or just your irresistible charm?” Dr. Yadav arrived with a booming laugh, clapping Dr. Dube on the back. “If it’s a photo with the master himself, I’m in! This could grace your biography someday, sir.”

We gathered under a grand archway, the faint outline of the Taj Mahal visible in the twilight beyond the windows—a poetic symbol of enduring legacy. As the shutter clicked, capturing us in that timeless frame (from left: Dr. Yadav, Dr. Dube, Dr. Jain, myself, and a colleague S.P.), Dr. Dube turned to me with a conspiratorial whisper: “In our field, P.K., it’s not just the research that matters—it’s the human stories we weave. Keep listening to them.” His words lingered like a gentle echo, encapsulating his philosophy: a brilliant intellect tempered by profound empathy.

That photograph, taken before Dr. Dube’s passing in 2005, became more than a snapshot; it symbolized the intergenerational bridge in Indian psychiatry. For me, it was a pivotal moment that fueled my career, reminding me that true expertise lies in kindness. In Dr. Dube’s biography, this encounter stands as a testament to his approachable spirit, inspiring future generations to humanize the science of the mind.

Born in 1926, Krishna Chandra Dube grew up in a world where mental health was barely understood, let alone discussed. As a young medical student, he was drawn to the mysteries of the human mind. “Why do we lock people away just because their thoughts wander differently?” he’d ask his professors, who often had no good answer. After earning his MBBS and a Diploma in Psychological Medicine from London, he returned to India, armed with ideas that were radical for their time. He wasn’t just a doctor; he was a visionary who saw patients as people, not problems.

The Agra Revolution

In 1957, Dr. Dube stepped into the Mental Hospital in Agra as its new Superintendent and Professor of Psychiatry. The place was a fortress of despair—locked wards, barred windows, and patients treated more like prisoners than people. He wasn’t having it.

“Open the wards,” he told his stunned staff one morning.

“But sir,” a nurse protested, “what if they run? What if they hurt someone?”

“They won’t,” Dube replied, his voice calm but firm. “They’re not animals. They’re human beings who need care, not cages.”

Within a year, the locks came off. Patients who’d spent years in isolation felt sunlight on their faces, some for the first time in decades. This wasn’t just a policy change; it was a statement: mental illness didn’t mean a life sentence. The hospital transformed into a hub of healing and learning, a place where students and doctors from across India came to study under the man who dared to rethink everything.

The Epidemiologist with a Mission

Dr. Dube wasn’t content with just fixing his hospital. He wanted to know how deep mental illness ran in India. In 1961, he launched the largest psychiatric epidemiological study the country had ever seen, covering Agra’s diverse population. Picture him trudging through dusty streets, clipboard in hand, talking to families, shopkeepers, and farmers.

“How’s your mind feeling today?” he’d ask, disarming even the most skeptical with his gentle curiosity.

The study, running until 1967, revealed a messy truth: mental disorders ranged from 9.5 to 370 per 1,000 people, depending on how you measured. It wasn’t perfect, but it was a start—a map of India’s mental health landscape that no one had dared to draw before. His work became the bedrock for future national surveys, exposing gaps in care that still challenge India today.

A Scholar and a Storyteller

Dr. Dube’s research wasn’t just numbers. He dug into the soul of India’s struggles with mental health. His paper “Patterns of Drug Abuse in India” traced addiction back to 2000 BC, weaving stories of ancient Indo-Aryan rituals into modern-day struggles with opium and cannabis.

“History shapes us,” he’d tell his students over chai at Agra’s Mughal Sheraton, where he often met colleagues like Dr. B.S. Yadav or Dr. R.K. Jain. “If we don’t understand where we’ve been, how can we fix where we’re going?”

His 21 published papers racked up 898 citations, earning him an H-index of 10—a quiet testament to his influence. From the British Journal of Psychiatry to the International Journal of Social Psychiatry, his words reached far beyond Agra, blending medicine with sociology and culture.

Shaping the Future

In 1960, Dr. Dube organized a massive psychiatric conference in Agra, a gathering that felt more like a movement. Picture him at the podium, eyes bright, rallying India’s top minds to rethink mental health. “We need to teach psychiatry like it matters,” he urged. That same year, the Indian Medical Council tapped him to design a national curriculum for postgraduate psychiatry training. His blueprint shaped generations of Indian psychiatrists, many of whom still credit “Dube Sir” for their passion.

The Man Behind the Mission

Dr. Dube wasn’t all work. Colleagues remember him as a man who loved a good debate, often over a plate of spicy tandoori at the Mughal Sheraton. “He’d argue about dopamine pathways one minute and the best way to make chai the next,” Dr. R.K. Jain once laughed. His warmth made him a mentor to many, but his fire kept everyone on their toes.

When he passed away in 1989, India lost more than a doctor—it lost a pioneer who saw mental health as a human right. His legacy lives on in the open wards of Agra’s hospital, the students he inspired, and the studies that still guide India’s mental health policies.

“Treat the person, not the illness,” he’d say, and those words echo through every corner of Indian psychiatry today.

. Dr. Dube’s legacy is tied to his transformative work at the Mental Hospital and his groundbreaking research. If you’d like me to dig deeper into any part of his life or work, just let me know!

Dr. Krishna Chandra Dube (1926–1989) was a distinguished Indian psychiatrist whose transformative leadership and pioneering research significantly advanced mental health care in India, particularly during his tenure at the Mental Hospital in Agra.

Early Life and Education

Born in 1926, Dr. K.C. Dube pursued his medical education with a focus on psychiatry, earning an MBBS and a Diploma in Psychological Medicine (DPM) from London. He was also a Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association (FAPA) and a Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences (FAMS). His academic affiliations included S.N. Medical College in Agra and a stint at the University of Bristol, reflecting his global exposure and expertise.

Career and Contributions

Dr. Dube’s most notable contributions came during his tenure as Professor of Psychiatry and Superintendent of the Mental Hospital in Agra from 1957 to 1975, a period often referred to as the institution’s “golden period.” Within a year of joining, he took the bold step of unlocking the psychiatric wards, a progressive move that emphasized humane treatment and patient dignity, challenging the era’s custodial approach to mental health care.

Under his leadership, the hospital became a hub for psychiatric research and education. Dr. Dube spearheaded the largest epidemiological study in Indian psychiatry from 1961 to 1967, investigating the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Agra. This study, conducted with his colleagues, laid foundational insights into mental health epidemiology in India, despite early studies showing wide variations in prevalence rates (9.5 to 370 per 1,000 population). His work helped standardize approaches to psychiatric research in the country.

Dr. Dube also made significant contributions to understanding substance abuse in India. His research, including the paper “Patterns of Drug Abuse in India,” explored the historical and sociocultural roots of drug use, dating back to 2000 BC in early Indo-Aryan civilization, providing a contextual framework for modern substance abuse patterns.

In 1960, he organized a landmark psychiatric conference at the Mental Hospital in Agra and was appointed convenor of a sub-committee by the Indian Medical Council to formulate a curriculum for postgraduate training in psychiatry, shaping the future of psychiatric education in India. His research output was prolific, with 21 published papers and a cumulative citation count of 898, earning him an H-index of 10. His work spanned medicine, sociology, pharmacology, toxicology, and pharmaceutics, with publications in prestigious journals like the British Journal of Psychiatry and the International Journal of Social Psychiatry.

Legacy

Dr. Dube’s tenure at the Mental Hospital in Agra marked a paradigm shift in Indian psychiatry, moving from institutional confinement to a more scientific and compassionate approach. His epidemiological studies laid the groundwork for subsequent national surveys, such as the National Mental Health Survey, which highlighted treatment gaps of 73–85% for mental disorders in India. Colleagues remembered him as a dynamic leader whose influence extended beyond clinical practice to policy and education. He was known to have collaborated with other prominent psychiatrists, such as Dr. B.S. Yadav, Dr. R.K. Jain, and Dr. S.P. Gupta, often engaging in professional discussions in settings like the Mughal Sheraton Hotel in Agra.

Dr. Dube passed away in 1989, but his contributions continue to influence psychiatric care and research in India. His work remains a cornerstone for understanding mental health challenges in the Indian context, blending clinical innovation with a deep understanding of cultural and historical factors.

Note: Some sources mention a Dr. K.C. Gurnani, a psychiatrist in Agra, but this appears to be a distinct individual, often confused due to the similarity in initials and location.

Dr. Krishna Chandra Dube (1926–1989) was a distinguished Indian psychiatrist whose transformative leadership and pioneering research significantly advanced mental health care in India, particularly during his tenure at the Mental Hospital in Agra.

Early Life and Education

Born in 1926, Dr. K.C. Dube pursued his medical education with a focus on psychiatry, earning an MBBS and a Diploma in Psychological Medicine (DPM) from London. He was also a Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association (FAPA) and a Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences (FAMS). His academic affiliations included S.N. Medical College in Agra and a stint at the University of Bristol, reflecting his global exposure and expertise.

Career and Contributions

Dr. Dube’s most notable contributions came during his tenure as Professor of Psychiatry and Superintendent of the Mental Hospital in Agra from 1957 to 1975, a period often referred to as the institution’s “golden period.” Within a year of joining, he took the bold step of unlocking the psychiatric wards, a progressive move that emphasized humane treatment and patient dignity, challenging the era’s custodial approach to mental health care.

Under his leadership, the hospital became a hub for psychiatric research and education. Dr. Dube spearheaded the largest epidemiological study in Indian psychiatry from 1961 to 1967, investigating the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Agra. This study, conducted with his colleagues, laid foundational insights into mental health epidemiology in India, despite early studies showing wide variations in prevalence rates (9.5 to 370 per 1,000 population). His work helped standardize approaches to psychiatric research in the country.

Dr. Dube also made significant contributions to understanding substance abuse in India. His research, including the paper “Patterns of Drug Abuse in India,” explored the historical and sociocultural roots of drug use, dating back to 2000 BC in early Indo-Aryan civilization, providing a contextual framework for modern substance abuse patterns.

In 1960, he organized a landmark psychiatric conference at the Mental Hospital in Agra and was appointed convenor of a sub-committee by the Indian Medical Council to formulate a curriculum for postgraduate training in psychiatry, shaping the future of psychiatric education in India. His research output was prolific, with 21 published papers and a cumulative citation count of 898, earning him an H-index of 10. His work spanned medicine, sociology, pharmacology, toxicology, and pharmaceutics, with publications in prestigious journals like the British Journal of Psychiatry and the International Journal of Social Psychiatry.

Legacy

Dr. Dube’s tenure at the Mental Hospital in Agra marked a paradigm shift in Indian psychiatry, moving from institutional confinement to a more scientific and compassionate approach. His epidemiological studies laid the groundwork for subsequent national surveys, such as the National Mental Health Survey, which highlighted treatment gaps of 73–85% for mental disorders in India. Colleagues remembered him as a dynamic leader whose influence extended beyond clinical practice to policy and education. He was known to have collaborated with other prominent psychiatrists, such as Dr. B.S. Yadav, Dr. R.K. Jain, and Dr. S.P. Gupta, often engaging in professional discussions in settings like the Mughal Sheraton Hotel in Agra.

Dr. Dube passed away in 1989, but his contributions continue to influence psychiatric care and research in India. His work remains a cornerstone for understanding mental health challenges in the Indian context, blending clinical innovation with a deep understanding of cultural and historical factors.

Dr. Dube’s contributions are specifically tied to the Mental Hospital and his epidemiological research.