In the misty foothills of Dehradun, where the Himalayas whisper secrets to the pines, stood St. Thomas’ High School—a bastion of discipline, dreams, and the occasional dash for freedom on the football field. It was here, in the 1970s and ’80s, that Mr. Moses reigned as the school’s Physical Training Instructor (PTI), a man whose presence alone could straighten a slouching spine or scatter a gaggle of giggling boys. Tall as a Deodar tree, dark-skinned with a build that spoke of unyielding strength, he cut an imposing figure: hair combed back in a slick, straight line like a drill sergeant’s dream, and always—always—with a cane tucked under his arm, not as an accessory, but as an extension of his booming authority. “That cane wasn’t just for show,” recalls Dr. P.K. Gupta, a former student who later carved his own path in medicine. “It whistled through the air like a referee’s whistle, quick to remind us that ‘left, left, right, left’ wasn’t optional.”

Born in the rugged heart of Uttarakhand—exact year lost to the fog of schoolyard legends—Mr. Moses embodied the old-school ethos of British Raj-era education, tempered by Indian grit. He wasn’t one for flowery introductions; his biography could be summed up in the echo of his commands across the dusty parade ground. But oh, what stories those echoes told. As the unchallenged in-charge of the school’s march past drills, he’d stride at the front like a one-man battalion, his voice thundering over the ranks: “Left! LEFT! Right! LEFT! Eyes front, you lot— or I’ll have you marching laps till the sun sets on Mussoorie!” The cadets, a mix of wide-eyed juniors and cocky seniors, would snap to attention, hearts pounding not just from the rhythm but from the sheer force of his timbre. It was said his bellow could reach the principal’s office two buildings away, and more than once, it did—summoning stragglers or silencing a mid-drill whisper.

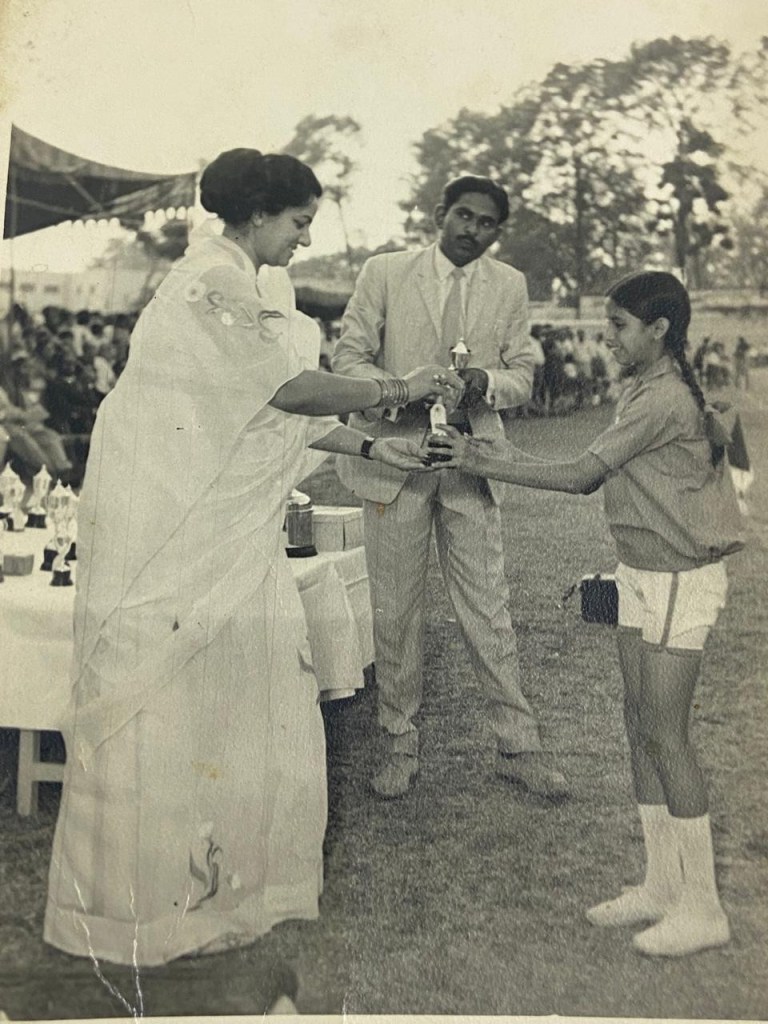

Sports were his kingdom, and under his watchful eye, every game was a battle worth winning. Mr. Moses had a knack for all things athletic—cricket, hockey, you name it—but football held a special chaos in his heart. The school’s equipment shed was his fortress, locked tighter than a miser’s purse. “No ball without my say-so!” he’d growl, key jangling like a warden’s. Enter the sly rebels: students like Lalit Khanna, the class prankster with a grin sharper than a corner kick. “We’d forge the principal’s signature on those chits—wobbly loops and all,” Dr. Gupta chuckles, eyes twinkling at the memory. “Lalit was a wizard with a pen; he’d mimic Father Principal’s flourish so well, even I believed it. Sneak the note under the door, wait for the click of the lock, and out would roll the ball. Mr. Moses would fume later, cane tapping his palm: ‘Who released the bloody orb? Speak up, or the whole team’s doing burpees!‘ But deep down, he loved the fire in us. Without those illicit games, we’d have been softer than idlis.”

Ah, but Mr. Moses was no polished orator—his English was a glorious tangle, raw and endearing, the kind that humanized a giant. He’d bark orders with a linguistic flair all his own: “Both of you three, come here—now!” or, mid-drill, “If you four boys don’t align, I’ll make you five regret it!” The class would stifle snickers, only to erupt when the English teacher, the ever-patient Mrs. Rao, swooped in like a grammar hawk. “Mr. Moses,” she’d correct gently, “it’s all three of you—not ‘both if you three.'” He’d pause, cane frozen mid-air, then boom a laugh that shook the rafters: “Achha, Madam ji, all three it is! But drill’s still on—left, left!” It was these slips that made him ours—not some distant taskmaster, but a man who sweated and stumbled alongside us. And the NCC cadets? Poor souls left behind after a sloppy maneuver would get his patented correction: “You two behinds—fall in, or face the cane’s kiss!” Followed by a wink when the English teacher wasn’t looking.

His partnership with Mr. Butler White, the school’s original PTI—a wiry Englishman with a whistle perpetually at his lips and skin pale as the Doon winter fog—added another layer to the legend. Mr. Butler, with his clipped Oxford accent and tales of Eton fields, handled the finesse: the perfect volley, the tactical feint. But when health or wanderlust called him back to Blighty in the mid-’80s, Mr. Moses stepped up seamlessly, blending Butler’s precision with his own thunderous flair. “He took the reins like he’d been born to it,” Dr. Gupta notes. “Where Mr. Butler whispered strategy, Moses roared it into reality.”

Years rolled by like monsoon clouds, and Dehradun changed—skyscrapers nibbling at the hills, cars honking where once only peacocks cried. Dr. P.K. Gupta, that scrawny boy who’d dodged more than a few cane swishes, had transformed into a renowned neuropsychiatrist. Fresh from his MD at SN Medical College in Agra, he’d hung his shingle at Deemag Clinic on Gandhi Road, a haven for minds adrift in Uttarakhand’s stresses. It was a crisp autumn day in the early ’90s when the clinic door creaked open, and in strode a familiar colossus—taller than memory, hair still slicked back, though silver threaded the black now. No cane in sight, just a sheepish grin.

“Doctor Gupta? Little PK from Thomas’? By Jove, you’ve grown a beard—and a whole clinic!” Mr. Moses boomed, enveloping the room in that voice, unchanged as the Ganges. Dr. Gupta froze, stethoscope mid-air, then broke into a laugh. “Sir! Mr. Moses? Sit, sit—before you march right through the wall. Tea? Or shall I call it ‘both if you one’?”

They talked for hours, the clinic emptying around them. Mr. Moses, retired but unbowed, shared tales of drills gone gloriously wrong: the time a cadet tripped into the principal’s rosebed mid-march, or how Lalit Khanna’s forged signatures nearly sparked a full-school inquisition. “You boys kept me young, PK—or at least kept the cane swinging,” he rumbled, eyes misty. “But look at you now, healing heads instead of bashing them. Makes a man proud.” Dr. Gupta, in turn, confessed how those booming commands had drilled resilience into him—the same grit that carried him through medical marathons. “Sir, without your ‘left, left,’ I’d still be fumbling right turns in life.”.

There was a junior PTI, Mr Thapa who was very athletic and used to run around the ground seriously trying to teach us football. He was good in gymnastics also. He later died after falling from a bus.

Mr. Moses left with a clap on the back that rattled the X-ray machine, promising to return with stories of his grandchildren’s escapades. He did, sporadically, until age finally sidelined him. But in Dehradun’s alumni circles, he’s immortal: the PTI who built men not just with muscle, but with memories. Tall, dark, unforgettably human—Mr. Moses, forever marching on.