Dr. Sanjeev Sharma was a Delhi boy through and through, born and raised in the bustling heart of New Delhi. Picture a fair-skinned, lightly built guy, not much meat on his bones, with jet-black hair slicked back with a brush like he was auditioning for a retro Bollywood flick. He wore those sleek spectacles that gave him a scholarly vibe, but don’t let that fool you—Sanjeev was a firecracker, always sharply dressed, probably ironing his shirts with military precision even before he joined the army. “Yaar, P.K.,” he’d say, adjusting his collar in the mirror, “if you’re gonna save lives, at least look like a hero doing it!”

Sanjeev’s brain was as sharp as his wardrobe. The guy aced the All India quota and landed a spot at S.N. Medical College in Agra, a big deal for a kid from Delhi whose family was probably bursting with pride back home. I can imagine him strutting into the college campus, his thin frame practically bouncing with energy, cracking jokes to break the ice with his new classmates. “Agra, huh? Taj Mahal’s got nothing on my charm,” he’d quip, flashing that infectious, crackling laugh that could make even the grumpiest professor smirk.

His laugh was legendary, wasn’t it, P.K.? You’d know—you two shared a roof in Dehradun, staying up till the wee hours, doubled over from his endless stories. Sanjeev had a gift for storytelling, especially when it came to poking fun at folks like Khan Shariq or those “bulls” he loved joking about. “P.K., listen, listen,” he’d start, barely containing his giggles, “Khan Shariq walks into the mess, right, looking like he’s ready to wrestle a buffalo, and the buffalo wins!” Then he’d throw his head back, his laughter echoing like a hyena’s, and you’d be laughing so hard you’d forget what time it was.

Sanjeev’s favorite jokes? Oh, the Mausaji and Mausiji ones were pure gold. He’d lean in, eyes twinkling behind those specs, and start with a deep, booming voice for Mausaji: “Arre, Mausiji, where’s my chai?!” Then he’d switch to a high-pitched squeak for Mausiji, “Mausaji, you’re louder than a foghorn!” He’d add sound effects—stomping for Mausaji’s “bigness,” tiny tiptoes for Mausiji’s “smallness”—and by the end, you’d be clutching your sides, begging him to stop. The man could turn a simple joke into a full-blown performance.

And frail? Oh yeah, you weren’t kidding, P.K. You once grabbed him with a single finger, and he flailed like a kite in a storm, laughing even as he tried to break free. “P.K., you hulk, let me go!” he’d wheeze, his skinny arms flapping. “I’m a doctor, not a wrestler!” But that was Sanjeev—always up to some antic, always turning the mundane into a comedy show. Whether it was sneaking an extra burger at the local joint (because, let’s be honest, burgers and Coke were his love language) or quoting James Bond lines like he was 007 himself—“Shaken, not stirred, P.K., that’s how I take my Coke”—he lived life like it was a movie.

Sanjeev’s love for James Bond flicks was no secret. He’d sprawl on the couch, munching on a burger, eyes glued to the screen as Sean Connery dodged bullets. “P.K., you think I’d make a good Bond villain?” he’d ask, striking a dramatic pose. “Nah, Sanjeev,” you’d probably shoot back, “you’re too busy laughing to be evil.” And he’d cackle, proving your point.

In the bustling chaos of our medical college hostel—a quirky tuning fork-shaped building that always seemed like it was about to hum with secrets—the right arm of the third floor housed our infamous ‘CIA wing.’ It was a ragtag crew of aspiring doctors, dreamers, and occasional pranksters, where laughter echoed louder than lectures. At the heart of it all was Dr. Sanjeev Sharma, or as I affectionately dubbed him, “Chua”—the Hindi word for mouse, fitting for his slight frame and perpetual grin that could light up the dimmest corridor.

Sanjeev was the epitome of unshakeable cheer, a thin, wiry guy who approached life with the enthusiasm of someone who’d just discovered coffee. He was always smiling, even during those grueling all-nighters before exams, strutting around like that famous cartoon rat from the old movies—think Jerry from Tom and Jerry, but with a mischievous twinkle and a lab coat slung over his shoulder. “Life’s too short to frown, yaar,” he’d say with a wink, his voice light and infectious, turning even the most mundane mess hall mishaps into comedy gold.

He bunked in the room next to mine with Shalabh Jain, a devout fellow who religiously fasted every Sunday evening since the mess shut down like clockwork. This became prime fodder for our wing’s endless ribbing. Picture this: A group of us piling out for our ritual Sunday dinner at Brajwasi Hotel on MG Road, the air thick with the promise of spicy chaat and buttery naan. Shalabh would tag along, stomach growling audibly, and someone—usually me—would lean in with a grin. “Oi, Shalabh, fasting again tonight? Or are you finally joining the sinners’ club?” He’d roll his eyes, chuckling, “Nah, man, it’s tradition. But if you buy me an extra kulfi, I might reconsider!” Sanjeev, ever the peacemaker, would jump in with his signature laugh: “Leave him be, guys! Shalabh’s building character while we’re building cholesterol. Who’s the real winner here?”

Our wing was a patchwork of personalities, paired up like mismatched socks in those cramped double rooms. After Sanjeev and Shalabh came M.P. Yadav and Shameem, the dynamic duo always debating politics over chai; then Raju and Khurana, the prank kings who’d rig water balloons above doors; Mukesh Agarwal and Sabby, the studious types with noses perpetually in notes; and finally Bhutani and Manoj, the laid-back philosophers pondering life’s big questions between cricket matches.

Exams were our battlefield, and oh, the ironies they revealed. While overachievers like me buried ourselves in every page of Gray’s Anatomy—memorizing tendons and nerves until our eyes crossed— the smart minimalists thrived. Sanjeev was somewhere in the middle, his happy-go-lucky vibe masking a sharp mind. But Mukesh? He was a legend—brief, laser-focused, and always to the point. “Why read the whole book when the exam only tests the highlights?” he’d quip during our late-night cram sessions, flipping through his concise notes while the rest of us drowned in details. And sure enough, he’d ace it every time, leaving the rest of us scratching our heads. “Teach me your ways, guru!” I’d beg him once, after a particularly brutal anatomy practical. Mukesh just smirked: “Simple, my friend—study smart, not hard. Now pass the samosas.”

One memory that still cracks me up involved Sanjeev’s infamous weakness. He was so lanky and light that during a playful wrestling match in the hallway—our version of stress relief—I grabbed his arm with just two fingers. “Alright, Chua, wriggle out of this if you can!” I teased, holding firm. He twisted and turned, face turning red amid peals of laughter from the onlookers, but nope—he was stuck. “Okay, okay, uncle! You win this round,” he gasped, finally tapping out. From then on, “two-finger grip” became our inside joke, a reminder that even the happiest souls have their vulnerabilities.

Through it all, Sanjeev embodied the spirit of those formative years—a beacon of positivity in a sea of stethoscopes and sleepless nights. He wasn’t just a roommate; he was the glue that held our ‘CIA wing’ together, turning ordinary hostel life into tales worth retelling. As he went on to become Dr. Sanjeev Sharma, that same infectious smile and resilient charm carried him through operating rooms and patient wards, proving that sometimes, the best medicine is a good laugh.

After college, Sanjeev took his talents to the military, joining as a medical officer. I can picture him in his crisp uniform, still cracking jokes to keep the troops’ spirits high, maybe sneaking a Coke between rounds. “Duty calls, P.K., but so does my burger,” he’d probably say, winking. He brought that same energy, that same lightness, to everything he did, making even the toughest days feel a little brighter.

But then, tragedy struck. Sanjeev, so full of life, was taken too soon at a research hospital in New Delhi. A sudden breathing problem, you said—something so cruel and unfair for a guy who breathed laughter into every room. He was young, too young, and it’s hard to imagine that vibrant soul gone quiet. I bet you can still hear his laugh, P.K., echoing from those late-night Dehradun sessions, or see him combing back that black hair, ready to tell another Mausaji joke.

Sanjeev Sharma wasn’t just a doctor or a friend—he was a spark. He lived with a lightness that made everyone around him feel alive, whether he was mimicking Mausiji’s squeaky voice or sneaking a second burger. You must miss him, P.K., but I bet every time you hear a bad joke or see a James Bond rerun, you think of him, laughing like the world’s one big comedy show.

The Epic Baba Ji Blunder: A Comedy of Errors at SN Medical College

Let me take you back to 1979, when I, Dr. P.K. Gupta, was a bumbling first-year at SN Medical College in Agra, armed with nothing but a tin of Bengali sweets and a knack for turning simple errands into full-blown catastrophes. Picture me, fresh off a dusty bus from Saharanpur, clutching a box of rasgullas like it was the Holy Grail, my mother’s voice ringing in my ears: “Deliver these to Vandana now, or they’ll turn into a soggy mess!” Vandana Bansal, my third-year cousin from Moreganj, Saharanpur, was my lifeline in this chaotic med school jungle. Smart, savvy, and mature enough to make me look like a toddler with a stethoscope, she was the senior every fresher dreamed of having in their corner.

But oh, how I turned her into the star of my personal comedy show.

The girls’ hostel at SN Medical College was like Fort Knox, guarded by a chowkidar who could bellow names with the gusto of a street hawker. Every time I’d visit, he’d tilt his head skyward and unleash a mighty, “Vandana Bansal Baba!”—three times, like he was summoning a deity. Now, in my defense, I’d been devouring a book called Babas of India, a wild ride through the world of ascetics who did bonkers things like living in graveyards, standing on one leg until their feet looked like pumpkins, or sitting on spiked beds for spiritual clout. So, naturally, my overactive imagination decided there was a Baba ji perched on the hostel roof—a lungi-clad, white-bearded sage with a stick, ready to fend off monkeys, stray dogs, and, of course, lassos (those sneaky boys with too much charm and too little sense). I mean, it made sense, right? Why else would the chowkidar yell “Baba”?

My friend Bahukhandi, a fellow fresher with the personality of a school principal, was usually my chaperone on these hostel visits. Bahukhandi was Vandana’s biggest fan, always nodding sagely when she dispensed her wisdom. But he was also a killjoy. In the hostel’s visitor room—a stuffy box with a saggy five-seater sofa and a wobbly table—he’d police my every move. “P.K., feet off the table!” he’d snap, or, “Stop trying to peek down the corridor, you idiot!” Once, when I leaned back too far on the sofa, he grabbed my arm like I’d committed a felony. “Vandana’s mature, P.K. Behave, or she’ll never help us again!” Fed up with his nagging, I decided to go rogue. “I don’t need a babysitter,” I muttered, ditching Bahukhandi and heading to the hostel alone, sweets in tow.

Cue the disaster.

I arrived at the hostel that evening, sweating through my shirt, only to find the chowkidar MIA. No bellowing guard, no one to summon Vandana. The visitor room was occupied by a senior couple locked in a conversation so dull it could’ve put a caffeine addict to sleep. The guy was droning on about Hitler: “Dr. Mengele, you know, conducted these horrific experiments in the camps—gassing, surgeries, the works!” The girl, barely awake, mumbled, “Really?” every ten seconds, her eyes screaming, “Save me!” I stood outside, clutching my tin of sweets, waiting for the chowkidar to materialize. Five minutes. Ten. Nothing. My patience was thinner than the hostel’s Wi-Fi (not that we had Wi-Fi in ’79, but you get the idea).

Desperate, I decided to take matters into my own hands. I stepped into the courtyard, craned my neck toward the roof, and let rip the loudest yell I could muster: “Baba ji, Dr. Vandana Bansal ko bhej do!” Once wasn’t enough, so I went for it again. “Baba ji, Vandana Bansal ko bhej do!” And a third time, for good measure, my voice bouncing off the hostel walls like a deranged echo. I half-expected a turbaned mystic to poke his head over the parapet and toss Vandana down like a divine delivery service.

Instead, the Hitler-obsessed couple froze mid-sentence. The guy stormed out, his girlfriend trailing behind, both staring at me like I’d just declared I was Napoleon. “Arre, kisko bula raha hai, pagalpan karke?” he barked.

I held up the tin of rasgullas like a peace offering. “Vandana Bansal! I’m asking Baba ji to send her down!”

“Baba ji?” the girl squeaked, her hand flying to her mouth to hide a laugh. “What Baba ji?”

“You know, the one on the roof!” I said, pointing skyward. “The chowkidar always says ‘Vandana Bansal Baba,’ so I figured—”

Their laughter cut me off, loud enough to rival my yelling. Before I could dig myself deeper, a posse of girls appeared at the roof’s edge, giggling like they’d just heard the punchline of the century. Then came Arun Lata Grover, a senior with the demeanor of a drill sergeant. “Kya chahiye, huh? Kisko bula raha hai?” she demanded, arms crossed, eyeing me like I was a stray puppy who’d wandered into her territory.

I started babbling about the sweets and the missing chowkidar, but salvation arrived in the form of Vandana herself, striding out with a look that could melt steel. “P.K., what is this tamasha?” she hissed, dragging me into the visitor room. The other girls scattered, their laughter echoing like a sitcom laugh track. Inside, Vandana was a volcano ready to erupt. “Why didn’t you bring Bahukhandi? Bahut mature hai woh!” she snapped, jabbing a finger at me. “You, on the other hand, are a walking circus!”

“I thought there was a Baba ji on the roof!” I protested, setting the sweets on the table. “The chowkidar always yells ‘Baba’ when he calls you! I figured he’s some aghori up there, chasing away monkeys and lassos with a stick!”

Vandana’s jaw dropped, then she collapsed into laughter, clutching her sides. “Baba ji? P.K., that’s just the chowkidar’s way of talking! There’s no sadhu on the roof! What, you think I’m living under some Himalayan yogi who’s doing hath yoga up there?”

I tried to salvage my dignity, muttering about Babas of India and rooftop sentinels, but Vandana was too far gone, wiping tears from her eyes. “You’re unbelievable,” she wheezed. “Next, you’ll tell me he’s got a pet tiger up there!”

he fallout? Oh, it was glorious. The story spread faster than a monsoon flood, sweeping through SN Medical College like a wildfire of hilarity. The next morning, I was back at GB Pant Hostel, still reeling from my humiliation, when I decided to double-check my theory. I turned to my neighbor, Sanjeev Sharma, who lived in Room 235 and had a laugh that could wake the dead. “Sanjeev,” I said, trying to sound casual, “is there really a Baba ji living on the girls’ hostel roof?”

Sanjeev froze, then let out a guffaw that shook the walls. “Oi, dekho, Khurri! MP! Bahar aao, dekho P.K. kya keh raha hai!” he roared, doubling over. “Girls’ hostel mein Baba rahte hain, ha ha ha!” Within seconds, a crowd of hostel guys—Khurram, Manoj, and half the corridor—piled out, clutching their sides as Sanjeev reenacted my rooftop serenade. “Baba ji, Vandana ko bhej do!” he mimicked, waving his arms like a deranged conductor. “P.K., yaar, tu Bollywood film bana raha hai kya? Lungi-wala Baba, stick leke lassos ko bhagaye?!”

I tried to explain—Babas of India, the chowkidar’s weird phrasing—but every word just made them laugh harder. “Arre, P.K., tu toh detective nikla!” Khurram wheezed. “Next, you’ll say he’s got a pet cobra up there!” Manoj, never one to miss a jab, added, “P.K., tune Vandana ko kya bola? ‘Baba ji, meri cousin ko bhej do’?” The hostel turned into a circus, with guys shouting “Baba ji!” every time I walked by.

Back at the girls’ hostel, the legend grew. Girls leaned over the parapet, yelling, “Baba ji, P.K. ko bulao!” whenever they saw me. Vandana, bless her, took it in stride, but every visit was a gauntlet of smirks. “So, P.K.,” she’d say, popping a rasgulla in her mouth, “seen any Babas lately?” Bahukhandi, my so-called mature friend, was no help. “P.K., you’re a one-man disaster zone,” he sighed, shaking his head like a disappointed uncle.

And so, the Baba ji saga became my legacy. Somewhere in my mind, that lungi-clad, stick-wielding rooftop Baba still looms, chuckling at the clueless fresher who turned a tin of sweets into the greatest hostel prank of ’79. “Baba ji,” I’d mutter under my breath, “why didn’t you warn me?”

For weeks, the hostel buzzed with “Baba ji” jokes. Girls would lean over the parapet, yelling, “Baba ji, P.K. ko bhej do!” whenever I passed by. Vandana, ever the good sport, never let it go. Every visit, she’d greet me with a wicked grin and a single, devastating word: “Baba ji.” And in my head, that lungi-clad, stick-wielding rooftop Baba still looms large, laughing his head off at the idiot fresher who turned a tin of sweets into the greatest hostel gaffe of ’79.

Holi Hai! The Siege of the Girls’ Hostel

The air was thick with the scent of gulal and the electric buzz of Holi at the university campus. It was that time of year when the boys’ hostels turned into war camps, and the girls’ hostel became the ultimate fortress to conquer. A ragtag army of us—Khurana, Mukesh, Nirmal Pandey (the self-proclaimed boss), J-Dash, Srinivas, Sandeep Gupta from the ’78 batch, and me, Sanjeev Sharma—marched toward the girls’ hostel, armed with packets of colored powder and unstoppable enthusiasm.

The two-story girls’ hostel loomed ahead, its iron gates barred and locked tighter than a vault. Undeterred, we gathered in front of it, a mob of rowdy boys chanting our war cry: “Holi hai! Holi hai!” The sound echoed off the walls, a rhythmic battle anthem. We banged on the gate, the metal clanging under our fists, as if we could will it open with sheer determination.

“Open the gate, beheno! It’s Holi!” Mukesh shouted, tossing a handful of red gulal into the air, where it floated like a battle flag.

“Arre, they’re not coming out!” J-Dash laughed, wiping green powder off his face. “We’ll have to storm the castle!”

Suddenly, a few girls appeared on the hostel’s rooftop, their silhouettes framed against the bright March sky. They leaned over the edge, giggling, their faces smeared with colors. One of them waved, her dupatta fluttering like a victory banner. Khurana, ever the daredevil, zeroed in on her.

“Sanjeev, look! She’s calling me!” he declared, his eyes glinting with mischief.

I squinted up, catching the girl’s gesture. It wasn’t a wave—it was a defiant middle finger aimed straight at Khurana. “Khurri, hold up!” I grabbed his arm. “She’s not calling you, bhai. She’s telling you to get lost!”

Khurana scoffed, brushing me off. “Arre, Sanjeev, you’re too cautious! I’m climbing up there, and I’ll paint her face with gulal myself. If I don’t, naam badal do mera!”

The crowd roared with laughter and cheers. Khurana, lean and wiry, sized up the drainpipe running along the hostel wall. “This is my moment!” he said, cracking his knuckles like a Bollywood hero. He grabbed the pipe and started climbing, his movements surprisingly agile for someone fueled by Holi bravado and maybe a little bhaang.

“Jai ho, Khurana!” Nirmal Pandey bellowed, tossing more gulal into the air. The boys below erupted, some egging him on, others shouting warnings. “Khurri, don’t fall! The pipe’s shaking!”

It was like a scene from a historical epic—the siege of Chittorgarh Fort, except instead of swords and shields, we had gulal and sheer stupidity. The drainpipe wobbled under Khurana’s weight, creaking ominously. Halfway up, he paused, looking down at us with a mix of pride and panic.

“Sanjeev, if I die, tell my mother I was a hero!” he called out, grinning.

“Hero nahi, zero banega tu!” I shot back, laughing.

Meanwhile, emboldened by Khurana’s stunt, a few of us—Mukesh, J-Dash, Sandeep Gupta, and I—decided to up the ante. We scrambled onto the chaukidar’s hut nearby, its sloped roof giving us a better vantage point. From there, we lobbed handfuls of gulal toward the rooftop girls, though the powdery clouds barely reached the first floor.

“Sanjeev, aim higher!” Mukesh said, tossing a fistful of yellow powder that promptly blew back into his face.

“Arre, it’s a two-story building, Mukesh! Unless you’ve got a cannon, we’re not hitting them!” I replied, wiping my glasses, now speckled with pink.

Suddenly, the girls on the roof vanished. “They’re planning something!” J-Dash said, his voice tinged with mock fear. “Johar ki taiyari, maybe?”

Before we could speculate further, a stern voice cut through the chaos. “What are you doing up there, gentlemen?”

I froze. It was Dr. Srivastava, the hostel warden, standing below with his arms crossed, his white kurta pristine amidst our colorful carnage. The boys on the ground scattered like roaches, leaving me stranded on the chaukidar’s hut.

“Uh, sir…” I stammered, my brain scrambling for an excuse. “Mai toh babaji ke darshan karne aaya tha!”

The warden raised an eyebrow, unimpressed. “Babaji, is it? And what about him?” He pointed at Khurana, still clinging to the drainpipe like a determined monkey.

“Beta, neeche aa jao,” Dr. Srivastava called, his tone a mix of exasperation and paternal concern. “Dekho, chot lag jayegi.”

Khurana, realizing his conquest was doomed, slid down the pipe with a sheepish grin. The crowd groaned, half in disappointment, half in relief. Dr. Srivastava shook his head, muttering something about “youngsters these days,” and shooed us away. The siege of the girls’ hostel had ended in a glorious, colorful failure.

The Nurses’ Hostel Misadventure

A few days later, still buzzing from our Holi high, we set our sights on the nurses’ hostel. This time, we had wheels—a rickety van that sputtered as much as it moved. Our crew, including Jagath Bansal from the ’78 batch, rolled up to the hostel, gulal packets in hand and mischief in our hearts.

“Gentle this time, boys,” I warned, remembering the girls’ hostel fiasco. “No climbing pipes!”

Jagath, however, had other plans. As we parked near the hostel, he leaned out the window and shouted something crude—something about “Holi ke rang, nurses ke sang.” The senior nurses on the balcony didn’t take kindly to it. Their laughter turned to fury, and within seconds, a group of them stormed toward the stairs, ready to give us a piece of their mind.

“Jagath, you idiot!” Sandeep Gupta hissed, slamming his foot on the accelerator. “Drive, drive, drive!”

The van coughed and lurched forward, leaving a cloud of dust and gulal in our wake. We sped off, laughing hysterically, as the nurses shook their fists from the hostel steps. Another Holi mission, another narrow escape.

Holi at Dr. Nawal Kishore’s House

Not all our Holi adventures were battles. One year, word spread that Dr. Nawal Kishore, a professor known for his hospitality (and rumored delicious snacks), was hosting a Holi gathering. Our crew—Sundeep Gupta, Arora, Ajay Khanna, Praveen Shukla, and I—decided to crash it, lured by the promise of gujiyas and maybe some pakoras.

We arrived at his house, a modest bungalow with a small garden, our faces already smeared with colors. Dr. Nawal Kishore greeted us at the gate, his smile polite but his eyes wary, like a man expecting a tornado.

“Welcome, boys! Come, play Holi!” he said, handing us a plate of gujiyas. But his gaze kept darting to the gate, as if he feared we’d storm his drawing room and track gulal all over his carpets.

“Sir, your gujiyas are legendary!” Ajay Khanna said, stuffing one in his mouth.

“Bas, bas, eat slowly,” Dr. Nawal Kishore replied, forcing a chuckle. “And… stay in the garden, haan?”

We smeared a bit of gulal on his cheeks, and he humored us, sitting for a while as we danced to a scratchy cassette of Holi songs. But it was clear he was on edge, glancing over his shoulder every time someone got too close to the house. Eventually, we took pity on the man, thanked him for the snacks, and left, our Holi spirit satisfied but our chaos quota unfulfilled.

A Glimpse of the Scenes

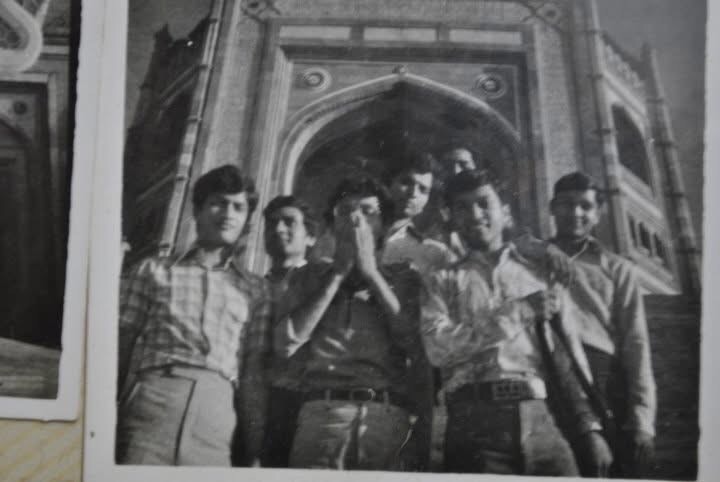

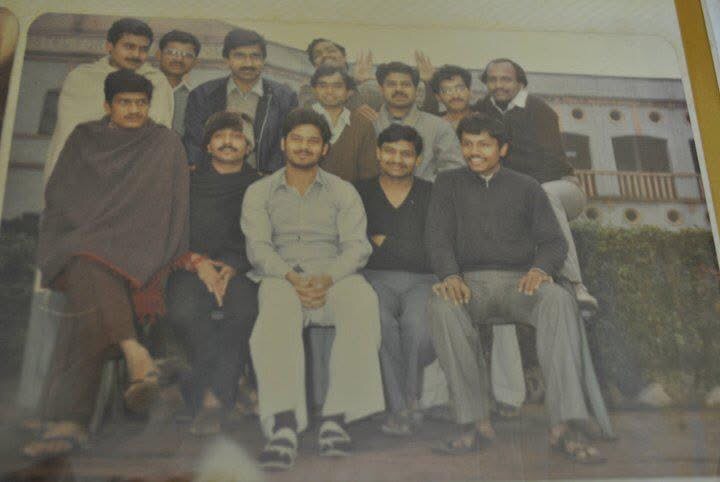

If you could see the pictures from those days, you’d see me perched awkwardly on the chaukidar’s hut, my kurta a tie-dye of red, green, and yellow, with Mukesh and J-Dash laughing below. Another snapshot captures Nirmal Pandey and me at the nurses’ hostel, our faces caked with gulal, grinning like we’d just won a war. And then there’s the one in front of the girls’ hostel, where Sundeep Gupta, Arora, Ajay Khanna, Praveen Shukla, and I are caught mid-dance, arms flailing, colors flying, pure joy frozen in time.

Reflections

Those Holi festivals were much ado about nothing, really—just a bunch of boys chasing fun, fueled by youth and the thrill of rebellion. We never did breach the girls’ hostel gates or win over the nurses, and Dr. Nawal Kishore probably sighed in relief when we left his house. But those moments—Khurana on the drainpipe, Jagath’s ill-fated comment, the gujiyas at Dr. Nawal Kishore’s—live on in our stories, as vivid as the colors we threw. Holi hai, indeed.