Back in the mid-1970s, St. Thomas’ School in Dehradun was a place of crisp worsted uniforms, morning assemblies under the deodar trees or Fraser house, and a palpable sense of excitement mixed with dread — especially in 1975–76.

Ravi Bhatia was one year my senior — I still remember him walking down the corridor with that easy smile and a slight swagger that only the confident ones had. I was Dr. P.K. Gupta (Class of ’76 ICSE), he was Class of ’75. But fate, and a rather nervous principal named Mrs. Ghose, had other plans.

When the school decided to introduce the 12th standard ISCE for the very first time, panic set in. The teachers, wonderful as they were for Classes 1 to 10, suddenly looked woefully under-equipped for the leap to senior secondary. The syllabus was tough, the stakes were sky-high — after all, every engineering and medical entrance exam in the country hinged on these marks.

One day, Mrs. Ghose called the entire Class XI (which later became the first Class XII batch) into the auditorium. I still remember her standing there, spectacles perched low on her nose, voice trembling slightly:

“Children, I have seen the mock test results. This is not Delhi Public School or Doon School. Our teachers have never taught Class XII before. The board is strict. If you fail, your future is finished. So I have taken a decision — some of you will have to repeat Class XI. It is for your own good.”

You could hear a pin drop. Half the batch was failed outright and asked to repeat Class XI — with us, their juniors!

Suddenly, boys who used to boss us around in the playground were sitting next to us again, red-faced, pretending it didn’t sting. But not Ravi Bhatia.

Ravi sailed through. Not only did he get promoted, but when the results came the following year — the very first Class XII ISCE results in St. Thomas’ history — he cleared it in first attempt, with marks that made even the strictest teachers nod in quiet approval.

I bumped into him near the water tank one afternoon after the promotion list was put up. He just grinned and said,

“Arre Gupta, ham to nikal gaye ab tumhara kya hoga, tumhen bahut mehnat karni hogi. Teachers are new to the curriculum”

I laughed and shot back, “Bhatia sahab, aap to nikal gaye. Hum to ab bhi dar ke maare kaanp rahe hain!”

He winked. “Bas thoda dimag lagao, ho jayega.”

And it did — for him, at least. That moment told me everything I needed to know about Ravi: calm under pressure, sharp as a tack, and always with that disarming sense of humour.

Years later, when people ask how a boy from a modest Dehradun school went on to become one of the most respected advocates in the country, I tell them this story — of a principal who failed half a batch out of fear, of a school taking its first nervous step into Class XII, and of one student who simply refused to blink.

That was Ravi Bhatia. Even back then, he was built different.

They were four siblings Atul, Laxmi, Ravi and Rama. All passed out from St Thomas school Dehradun. Even as kids, the Bhatia siblings arrived at St. Thomas’ in style. Every morning, a black Fiat would purr up to the school gate, and out stepped Ravi (senior, cool, untouchable) and his younger sister Ruma, my classmate, both waved off by their father—an immaculately suited advocate who practised at the Dehradun District Court. To us, he looked like he had walked straight out of a courtroom drama. We’d nudge each other and whisper, “Dekho, vakil sahab aaye apne bacchon ko chhodne!”

Poor Ruma, though, had a permanently rebellious stomach or had a weak liver. Motion sickness, spicy aaloo paratha breakfast, nerves—anything could set it off. She was sweet, soft-spoken, and perpetually pale, like a heroine in a tragedy who just needed one good burp to feel better.

One glorious morning in Class VI, Mrs. Kaur—tall, stately, and the proud owner of the tallest, most perfectly sprayed bouffant in the entire staff room—was taking maths. (Fun fact: she was the elder sister of our classmate Jitender Singh. Both siblings eventually migrated to Canada and are probably laughing about this story over butter chicken in Toronto right now.)

Mrs. Kaur had this unique checking style. She’d sit at her desk like a queen on a throne, and one by one we had to walk up, stand behind her, and wait while she ran her red pen through our sums. If you made a mistake, she’d tap the page ominously and say, “Beta, yeh kya kiya? Phir se samjhaana padega.”

Ruma’s turn came.

We noticed the warning signs immediately: the slight swaying, the hand on the tummy, the look of pure doom. Someone hissed from the back, “Arre Ruma ko phir se aa raha hai!” But there was no escape; Mrs. Kaur had already barked, “Ruma Bhatia, jaldi!”

Ruma dragged herself up, stood behind the chair, and tried to focus on long division while her insides plotted mutiny.

Thirty seconds of silence.

Then the sway turned into a full nautical roll.

“Ruma, kya hua?” Mrs. Kaur asked without turning, still marking.

That was the trigger.

Ruma’s cheeks puffed. Her eyes widened in pure panic. She tried to pivot left—no exit. Pivot right—blocked by the desk. In one tragic, slow-motion second, Mount Vesuvius erupted—straight onto the majestic bouffant.

SPLAT.

A perfectly half-digested piece of omelette (with visible bits of onion and chilli) landed right on top like a grotesque cherry on a very unhappy cake.

Time stopped.

Mrs. Kaur froze, pen mid-air. Then the smell hit her. She leapt up with a warrior cry that was half-scream, half-growl—“HAAAAAYE RAMAAA!”—and bolted for the door, one hand clamped over her hair, trying to shake off the omelette like it was radioactive.

We watched, open-mouthed, as she sprinted out of Gill House, down the corridor, across the basketball court, the morning sun catching the glistening omelette crown jewel so brightly it could have guided ships ashore.

From the window we heard Jitender Singh, her own brother , shout in glee, “Didi, OMELETTE!!!”

The class dissolved into chaos. Boys were rolling on the floor. Girls were screaming and laughing at the same time. One boy actually fell off his chair.

Ruma stood there, mortified, hands over her face, whispering, “I’m going to die… I’m actually going to die…”

I passed her my water bottle and said, “Ruma, tu legendary ho gayi. Aaj ke baad koi teacher tujhse copy check karwane se pehle do baar sochega!”

Years later, whenever old Thomasonians meet, someone inevitably brings up “The Great Bouffant Incident of 1972”. And Ravi Bhatia—cool, composed Ravi—still laughs till he cries and says, “My poor sister never lived it down. Instant respect through vomit!”

That, ladies and gentlemen, is the Bhatia legacy: fearless in the courtroom, infamous in the classroom—one sibling arguing cases before High Court judges, the other accidentally anointing a teacher with breakfast.

Only at St. Thomas’.

Ravi Bhatia was born in the misty hills of Dehradun in 1960, into a family where justice wasn’t just a profession—it was a calling. His father, Bhim Sen Bhatia, was a renowned criminal advocate in the local courts, known for his sharp wit and unyielding defense of the underdog. From a young age, Ravi watched his father pace the living room, rehearsing arguments for high-stakes cases. “Son, the law isn’t about winning,” Shankar would say over evening chai, his voice gravelly from years of courtroom battles. “It’s about standing tall for what’s right, even when the world bends against you.” Those words planted a seed in young Ravi, shaping his destiny.

Ravi’s early education unfolded at St. Thomas’ College in Dehradun, a prestigious institution nestled amid pine forests, where discipline and excellence were as much part of the curriculum as academics. He attended until 1978, graduating with honors in his higher secondary exams. Classmates remember him as a bright, charismatic boy with a knack for debate. “Ravi could argue his way out of detention,” one old school friend later recalled with a chuckle. But beneath the confidence lay the pressure of living up to his father’s legacy. After school, Ravi pursued law at a university in Delhi, earning his degree in 1983. Returning to Dehradun, he joined his father’s firm, stepping into the courtroom with the same fire that had defined Shankar.

The early years of his practice were golden. Ravi quickly made a name for himself, handling everything from property disputes to criminal defenses. By the mid-1980s, he was a rising star in Uttarakhand’s legal circles, often seen in the bustling Dehradun courts, his briefcase stuffed with case files. “Justice delayed is justice denied,” he’d quip to junior lawyers, echoing his father’s mantras. But success came with shadows. The stress of long hours, the weight of lost cases, and the isolation of a demanding career began to erode his spirit. Social gatherings with colleagues turned into late-night drinking sessions, and what started as a way to unwind spiraled into dependency. “Just one more, Ravi,” friends would say, clinking glasses. “You’ve earned it after that victory today.” But one became many, and alcohol became his silent companion.

By the early 1990s, Ravi’s health deteriorated. His once-sharp mind fogged, and his hands trembled during cross-examinations. Diagnosed with alcoholic liver disease in 1995, he faced the harsh reality of cirrhosis. “How did it come to this, Papa?” Ravi confided in his aging father during a rare vulnerable moment at home. Shankar, his eyes heavy with worry, replied, “We fight battles in court, but the hardest ones are within ourselves. You need help, son—not just for you, but for those who look up to you.” The liver failure hit hard; hospital stays became frequent, and Ravi’s practice suffered. Friends distanced themselves, and the man who once commanded respect now faced pitying glances.

It was in the depths of despair that Ravi found a lifeline. Inspired by stories of recovery he’d read during sleepless nights, he decided to confront his demons. In 1997, he founded the first Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) group in Dehradun, gathering a small circle of fellow strugglers in a modest community hall. His meeting used to be held in st Joseph’s academy, Dehradun. He even invited me to come over and I went. I even used to sent patients there seeing the great results of AA. “Hello, I’m Ravi, and I’m an alcoholic,” he’d begin each meeting, his voice steady despite the pain. The group grew, drawing people from all walks—teachers, businessmen, even other lawyers. Dialogues in those sessions were raw and transformative. One evening, a young attendee shared, “I lost my job because of the bottle. How do I start over?” Ravi, drawing from his own scars, responded, “One day at a time, my friend. We don’t erase the past; we build on it. Remember, rock bottom is a solid foundation for rebuilding.” Under his leadership, the group not only helped members sober up but also advocated for awareness about alcoholism in the conservative hill town.

Ravi’s involvement in AA marked a turning point. He improved remarkably—his liver stabilized with medication and abstinence, and he returned to practice with renewed vigor. By the early 2000s, he was mentoring young advocates and speaking at local events about addiction’s grip. “I was given a second chance,” he’d tell audiences, “and now I want to give others theirs.” His father, who passed away in 2005, lived long enough to see his son’s redemption, beaming with pride at an AA anniversary event. “You’ve become the advocate I always knew you could be—not just for others, but for yourself,” Shankar whispered to him that day.

Ravi Bhatia never did anything by halves.

When he argued a case, he argued it like the courtroom was the last battlefield on earth.

When he laughed, the room shook.

And when, somewhere along the way, he took to alcohol, he took to it with the same terrifying thoroughness—like a fish that doesn’t just swim in water, it breathes it, lives it, marries it.

His father, the venerable advocate we all called “Vakil Sahib”, first brought him to my clinic one quiet winter afternoon in the late ’90s. The old man’s sherwani was impeccable as always, but his eyes were tired. Ravi walked in behind him, still handsome, still that schoolboy swagger, only now it was unsteady. He gave me the same lopsided grin I remembered from the St. Thomas corridors and said,

“Arre Dr. Gupta, ab aap hi bacha lo. Main to apne aap se haargaya hoon.”

A few months later he came again, this time with Ruma. The three of them sat in front of me—the formidable Bhatia trio under the harsh tube-light of my little OPD room. I explained the options: Disulfiram medication, counselling, possible hospitalisation, the risks, the relapses, the long road. I looked at them and asked the hardest question we doctors ever ask:

“Can you handle what this treatment might demand? Because half-measures won’t work here.”

Ruma’s eyes filled up. Vakil Sahib slowly shook his head.

“Nahi Doctor sahab… hum itna bada risk nahi le sakte.”

Ravi just listened, fingers drumming on his knee. Then he looked straight at me and said softly,

“Doctor sahab, main le sakta hoon. Bas aap bataiye kya karna hai.”

That was Ravi. Where others hid, he stood up. Where others denied, he declared war.

I saw him months later at a public function in Dehradun. Most people would have slunk into a corner with a soda water. Not Ravi. He climbed onto the stage, took the mike, and in that deep baritone that once terrorised opposing counsel, announced to a stunned audience:

“Mera naam Ravi Bhatia hai, aur main alcoholic hoon. Main haar chuka hoon is daru se. Lekin ab jeetna hai. Aap sabke saamne keh raha hoon—main wapas apni zindagi churata hoon aaj se.”

You could have heard a pin drop. Then someone at the back started clapping. Within seconds the hall was thundering.

That honesty became his sharpest weapon. Most of us spend lifetimes running from our truths. Ravi turned around, stared his demon in the eye, and introduced it to the world by name.

He fought. Relentlessly. He co-founded Nijaat, the rehabilitation centre in Dehradun that has since pulled hundreds out of the same abyss. He became the man alcoholics called at 2 a.m. when the craving hit like a truck. He would drive across town, sit with them on footpaths, share his own horror stories, and say,

“Main bhi wahan tha bhai. Raat bhar bathroom mein baitha rota tha. Tu akela nahi hai. Chal, ek din aur jee lete hain.”

At our school reunion in 2018, the bar was flowing—old boys trying to drown thirty lost years in single malt. Someone shoved a glass towards Ravi.

“Arre yaar, ek peg to banta hai, reunion hai!”

Ravi smiled, raised his glass of nimbu pani, and said loudly enough for the entire table to hear:

“Bhailog, maine apna quota poora kar liya life mein. Ab mera peg yeh hai—aur ismein ek boond bhi nahi daal sakta. Sorry, rules are rules.”

He tapped his heart when he said “rules”.

We raised our glasses—some with whisky, most now with respect—and toasted the man who once lost a war and then won it so completely that he built a lighthouse for everyone else still drowning.

Ravi Bhatia taught us that real courage isn’t the absence of weakness; it’s the decision to stand up in front of the world, bleeding, and say:

“This is me. Broken. But watch me put myself back together.”

If even one person reading this finds the strength to make that same declaration, Ravi will smile somewhere and say,

“Chalo, ek aur jeet gaye.”

Ravi’s story is one of human frailty and resilience—a reminder that even heroes stumble, but it’s the rise that defines them. Through his journey, he turned personal pain into communal healing, leaving Dehradun a little kinder for those battling unseen wars.

The Enduring Ripple: How Alcoholics Anonymous Transformed Lives in Dehradun

In the serene valleys of Dehradun, where the Himalayas whisper ancient secrets and the air carries the scent of pine, a quiet revolution began in the late 1990s. Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) arrived not with fanfare, but with a simple promise: hope for those drowning in despair. Founded globally in 1935 by Bill Wilson and Dr. Bob Smith in Akron, Ohio, AA made its way to India in 1957. But in Dehradun—affectionately called Doon—it took root on July 8, 1998, marking the start of a fellowship that would touch thousands of lives over the next quarter-century.

Picture this: A modest room in a community hall, dimly lit by a single bulb, where strangers become confidants. “Hi, I’m Saurabh, and I’m an alcoholic,” one man begins, his voice steady after two decades of sobriety. “It started with social drinks after work, but soon it owned me—lost jobs, broken family ties.” Around him, nods of recognition ripple through the group. Saurabh, a Dehradun resident, credits AA meetings for his turnaround. “These gatherings aren’t about judgment; they’re about sharing the raw truth. One meeting at a time, I learned life could be joyful without the bottle.”

AA’s impact in Dehradun isn’t just anecdotal—it’s woven into the fabric of the community. By 2014, the city hosted four meetings a week, drawing 30-odd participants each time, including locals, foreign tourists seeking solace amid their travels, and even referrals from doctors like Dr. Sandeep Gupta. “Moral support from peers who’ve walked the same path is invaluable,” Dr. Gupta explains in conversations with attendees. “It’s not therapy; it’s real-life proof that recovery is possible.” Nearby towns like Haridwar, Roorkee, and Gopeshwar joined the fold, extending the network. Family members, too, found refuge in Sunday sessions, where one anonymous supporter shared, “Watching my husband spiral was hell. AA taught me I’m not alone—we’re all in this fight together.”

Fast-forward to 2023, and AA celebrated 25 years in Doon with quiet pride. The fellowship had grown to include regular gatherings in Bhowali, Bheemtal, Rishikesh, and even Saharanpur. No dues, no politics—just a desire to stop drinking and help others do the same. “We’ve seen lives rebuilt,” says Ravi, a local contact (9897331481), echoing the global ethos. Queries pour in—3 to 4 per week—from desperate souls. Awareness campaigns, through pamphlets, college lectures, and door-to-door outreach, have demystified addiction. One success story? A young professional named Sahil (name changed), who relapsed multiple times before AA’s persistent support stuck. “Sharing my slips-ups here keeps me accountable,” he confides. “It’s like a lifeline—I leave each meeting stronger.”

The ripple effect extends beyond meetings. Rehabs like Jeevan Sankalp in Dehradun, founded by a sober AA/Narcotics Anonymous member, blend spirituality with recovery, boasting stories of residents achieving independent living. “From rock bottom to running my own life—AA showed me the way,” shares one alumnus in a viral reel. 67 In nearby Haridwar, a recent AA gathering revealed members’ deep empathy: “The pain on their faces for fellow sufferers was palpable,” notes a report. “Anonymity lets us focus on healing, not shame.”

Personal tales amplify the impact. Take Vibhor Anand, a lawyer who hit bottom en route to a Dehradun rehab in 2021. “That dhaba stop on the Delhi-Dehradun highway was my wake-up call,” he recounts in a thread. After multiple stints, AA’s principles guided him to 24 months sober. “It’s not just quitting—it’s rebuilding trust, family, self.” 45 Or Ethirajan Srinivasan, who witnessed three middle-aged villagers quit lifelong habits via an NGO akin to AA. “They approached for help, and now they’re free—proof that recovery serves humanity.”

Statistically, AA’s global success rate hovers around 27-35% for sustained abstinence, but in Dehradun, the real metric is transformed lives: fewer relapses, mended families, and a community less burdened by addiction’s shadow. Amid Uttarakhand’s rising alcoholism—exacerbated by easy access and cultural shifts—AA stands as a beacon. As one member puts it, “We don’t promise miracles, just one day at a time. But those days add up to a lifetime.”

In Dehradun, AA isn’t just a program; it’s a movement of quiet heroes, turning personal battles into collective victories. If you’re struggling, reach out—helpline 8979734417. The door is always open, and the first step? Admitting you’re ready for change.

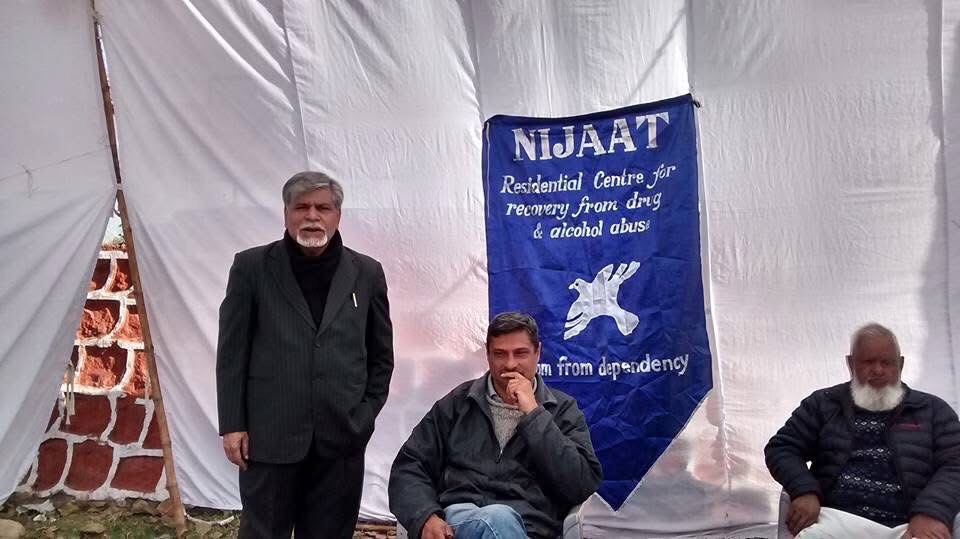

Whispers of Freedom: The Quiet Miracles of Nijaat

Nestled on the quiet fringes of Dehradun, where the Himalayan foothills whisper secrets to the wind, Nijaat stands as a sanctuary born from raw necessity. Founded in 2002 by a trio of determined souls—Ravi Bhatia, Saurabh Malhotra, and Dr. Rehmat—it began in a rented house with just 10 beds and a fierce belief: addiction isn’t a sentence, but a story waiting for its plot twist. “Nijaat” means freedom in Urdu, and for over two decades, this non-profit haven has handed keys to more than 1,000 lives locked in chains of alcohol, drugs, and despair. No locked doors here—clients walk in, and they choose to stay, a radical trust that echoes Ravi’s own battle: “I lost control once. Now, I teach others to reclaim it, one willing step at a time.”

What makes Nijaat more than a facility? It’s the stories—the raw, unpolished testimonies that ripple out like pebbles in the Yamuna. These aren’t glossy triumphs; they’re gritty comebacks, laced with humor, heartbreak, and that stubborn spark of humanity. Gathered from those who’ve walked its paths, here’s a glimpse into the lives reshaped, where “recovery” isn’t a finish line but a daily dawn.

Ayush’s Silver Lining: From Classroom Dropout to Stage Spotlight

Picture this: a 21-year-old kid from Doon’s elite circles, Ayush (name changed for the old wounds), who had the world on a platter—fancy cars, endless parties, the works. But by his late teens, that “average guy” allure twisted into a vortex of substances. “I thought it made me exciting,” he later chuckled in a dimly lit group session, his voice steady but eyes distant. “Turned out, it just made me vanish.” School? Dropped. Dreams? Buried under binges. His family, shattered, shipped him to Nijaat under the Alcoholics/Narcotics Anonymous program—not once, but four grueling rounds.

The turning point? Those midnight meetings in the center’s modest hall, where flickering lanterns cast shadows like old ghosts. “One night, this grizzled uncle—been sober 15 years—looked at me and said, ‘Beta, addiction’s like borrowing tomorrow’s peace. Pay it back, and you’ll own the sunrises.'” Ayush leaned in, scribbling notes on a crumpled napkin. Daily check-ins followed: yoga at dawn, therapy that peeled back layers like onion skins, and street plays where he’d act out his own rock bottom to wide-eyed locals.

Fast-forward: Clean for years now, Ayush traded parties for podiums. Enrolled in mass communication, he snagged “Best Speaker of the Year” at his college, his voice booming where silence once reigned. “Nijaat didn’t fix me,” he told a rapt audience at a Dehradun awareness workshop, mic in hand, grin wide. “It handed me the tools and said, ‘Build your own damn ladder.'” Today, he mentors dropouts, his story a beacon for the one-third of Nijaat’s under-30 crowd—youngsters who, like him, mistook escape for thrill. 5

Vikram’s Wall-Jump Wake-Up: From Escape Artist to Empathy Architect

Vikram wasn’t the villain in his tale—he was the anti-hero, sneaking out like a shadow in the night. Admitted in Nijaat’s early days, when the center was still figuring out its heartbeat, he embodied the chaos Ravi and team wrestled with. “We started strict—four months minimum, no frills food, long therapy marathons,” Ravi once shared over chai, his laugh warm but wry. “Thought addicts needed the boot camp treatment. Boy, were we wrong.”

Vikram, a 28-year-old mechanic whose hands shook more from withdrawals than wrenches, tested every boundary. “I’d eye that compound wall like it was my getaway car,” he confessed years later, during a Nijaat alumni campfire, flames dancing in his sober eyes. First escape: midnight, fueled by borrowed cigarettes from a roommate. He vaulted over, landed in the scrub, and hitched to town—only to wake in a ditch, penniless and puking. Back he came, not dragged, but walking, head hung low.

The staff didn’t scold; they sat him down with a cup of kadak tea. Saurabh Malhotra, the unflappable administrator, leaned forward: “Bhai, that wall’s not keeping you in—it’s keeping the old you out. Jump if you must, but ask: Who’s waiting on the other side?” It stuck. Vikram stayed, swapping sarcasm for sessions, where he’d sketch engines from memory during art therapy—blueprints of the life he wanted to rebuild.

Two years sober, Vikram’s no longer fixing bikes; he’s fixing futures. He co-leads Nijaat’s outreach—door-to-door chats in Dehradun’s back alleys, street plays that turn addicts’ shame into shared songs. “I jumped walls to run,” he quips to new admits, “but the real leap? Staying. Now I build bridges instead.” His story’s etched in the center’s growth: from those early escapes to a 90% completion rate today, proving love trumps locks every time.

Meera’s Silent Symphony: A Mother’s Melody of Mercy

Not all battles are solo; some are symphonies of second chances. Meera, a soft-spoken widow from Dehradun’s outskirts, arrived at Nijaat not for herself, but trailing her 19-year-old son, Aryan—hooked on heroin after a factory layoff crushed his spirit. “He was my melody,” she murmured in her intake interview, voice cracking like dry earth. “Now he’s a dirge I can’t silence.”

Nijaat’s family program wrapped them both in its arms—counseling for her grief, group hikes for his rage, and evenings where they’d cook together in the communal kitchen, chopping onions through tears and tentative laughs. One dusk, as the sun dipped behind Mussoorie hills, Aryan handed her a lopsided roti. “Ma, remember when I’d burn them on purpose to make you scold me? Just to hear your voice rise like song?” She nodded, and for the first time in months, they ate without the ghost of needles at the table.

A year on, Aryan’s clean, apprenticed as an electrician—wiring homes, not wrecking his own. Meera? She’s the unofficial “Nijaat Nani,” baking for workshops and sharing her mantra: “Addiction steals voices, but family? We amplify them.” Her impact echoes in the hundreds Nijaat reaches yearly through awareness campaigns—street plays in bazaars, school talks that snag students before the hook sinks in. “We don’t just heal addicts,” Saurabh says, echoing the center’s ethos. “We mend the worlds they leave behind.” 1

These threads—Ayush’s eloquence, Vikram’s vigilance, Meera’s melody—weave Nijaat’s true tapestry. Over 20 years, it’s birthed “firsts”: Dehradun’s inaugural residential de-addiction spot, a model of voluntary healing that’s inspired Uttarakhand’s network of nasha mukti kendras. Funded by trusts like Bethany and powered by volunteers, it treats with dignity—no judgments, just tools: 12-step meetings, yoga under deodars, counseling that cracks open hearts like walnuts. 3

Yet, the real magic? The referrals. Ex-clients like Vikram send kin, whispering, “This place doesn’t chain you—it unchained me.” In a 2010 documentary snippet, a long-term resident summed it: “Here, five years feels like five minutes of grace.” As Ravi Bhatia often used to toasts at reunions, nimbu pani raised high: “Freedom isn’t given. It’s grabbed, one story at a time.”

Tragically, the damage from years of abuse caught up. Despite his recovery, complications from liver failure resurfaced. On November 21, 2023—exactly two years ago —Ravi Bhatia passed away at 63 years, surrounded by family, Thomasians and AA members in a Dehradun Max hospital. His death was a quiet one, but his legacy echoed loudly. The AA and Nijaat group he started thrives to this day, having helped hundreds reclaim their lives. In the words of a mentee, “Ravi didn’t just fight cases; he fought for souls.”

If Nijaat’s echoes call to you—seeking help or sharing your own—reach out. In the shadow of the mountains, freedom’s always just a step away.