FROM MONGOLISM TO DOWN SYNDROME – A LESS KNOWN JOURNEY

You’ve heard of Down Syndrome. But do you know why it’s called that?

Most people assume it’s descriptive. Something about “down” or delayed development.

They’re wrong.

The name honors a man who changed everything for people society had written off as worthless.

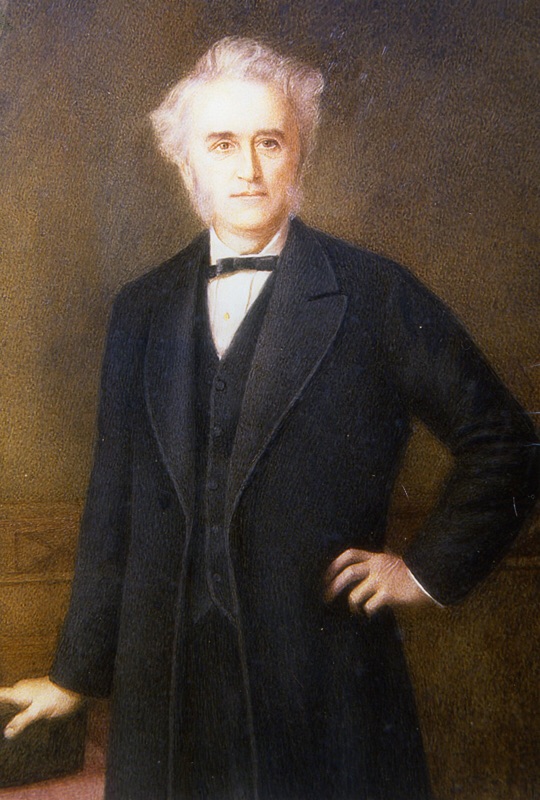

John Langdon Down was 29 years old, a newly graduated physician with gold medals in medicine, surgery, and obstetrics. He could have practiced anywhere in London. Made a fortune treating wealthy patients.

Picture a chilly autumn evening in 1828, in the little Cornish town of Torpoint. A baby’s cry cuts through the apothecary shop above which the Down family lives. The midwife wraps the newborn in a blanket and hands him to his mother, Alice.

“There you are, my love,” she whispers, exhausted but smiling. “John Langdon Down. You’ve got your father’s stubborn chin already.”

Little did anyone know that this pharmacist’s sixth child would grow up to change the way the world saw thousands of other children.

John was a dreamy, book-mad boy who spent more time reading medical journals in his father’s shop than playing down by the harbour. At 14 he was already helping compound medicines, and by 18 he’d decided: London. Medicine. No arguments.

In 1856, after scraping through exams and working as a surgeon’s assistant, he landed a job no one else wanted — medical superintendent of the Earlswood Asylum for Idiots in Surrey. (Yes, that was the actual name back then; the word hadn’t yet picked up its sting.)

On his very first day, the matron handed him a huge ring of keys and said, “Good luck, Dr. Down. Half of them can’t speak, most bite, and the governors think fresh air is dangerous. God help you.”

John walked the echoing corridors, looked into bright, bewildered eyes, and felt something shift inside him.

He later told his wife Mary one night over supper:

“I expected monsters, Mary. That’s what they’d taught us at university — degenerates, throwbacks, lost causes. But these are children. Just… children who learn differently. Someone has to speak for them.”

And speak he did.

He threw out the shackles, shortened the locked-ward hours, started music classes, got the residents gardening, and — scandalously — invited local villagers to watch the annual Christmas play performed by “idiots.” The audience wept at how beautifully the residents sang.

In 1866 he published a paper that would make him famous (and later unfairly infamous). He called it “Observations on an Ethnic Classification of Idiots.” In it he noticed that some of his patients had physical features — the flattened face, the almond-shaped eyes, the single crease across the palm — that reminded him of people from Mongolia. In a clumsy but well-meaning attempt to argue they were not “degenerate Caucasians” but a distinct and ancient type, he called the condition “Mongolism” and the children “Mongoloids.”

He stood in front of the stuffy Ethnological Society of London and declared:

“These children are not a step backwards. They belong to the great Mongolian family. Here is proof that different races can appear within the same parents — a reversion, yes, but not a degradation.”

The room erupted. Some applauded his compassion; others hissed at the idea of “racial throwbacks.”

John didn’t care about the hissing. He cared that for the first time someone had described the syndrome systematically and — crucially — insisted the children were lovable and teachable.

Back at Earlswood, a little girl named Lucy once tugged his coat-tails.

“Dr. John,” she lisped, “am I really a flower like you say?”

(He always told them they were “flowers in God’s garden — just slower to bloom.”)

He crouched down. “The rarest flower of all, Lucy. A Christmas rose in springtime.”

Years later, in 1868, he and Mary left Earlswood to open their own private home for children with intellectual disabilities in Normansfield, Teddington — a place of light, music, and laughter. He built a theatre there. Patients acted Shakespeare. Queen Victoria sent a telegram of praise.

He never retired, really. On the morning of 7 October 1896, he kissed Mary goodbye, said he felt “a bit under the weather,” went to his study to finish a letter, and quietly died at his desk — pen still in hand — aged 67.

His last words to a nurse the day before had been typical:

“Tell the children I’ll see them at rehearsal tomorrow. We’re doing Midsummer Night’s Dream, and I’m determined Puck shall have the last laugh.”

Today we call the condition he described Down syndrome — a name changed in the 1960s at the request of Mongolian delegates to the WHO, who found the old term hurtful. Modern genetics has shown it’s caused by an extra chromosome 21, not racial “reversion.”

But strip away the outdated language, and John Langdon Down still shines: the doctor who looked at children the world had written off and said, “No. They are human, they are valuable, and they can be happy.”

And in the quiet theatre at Normansfield (now a museum), if you listen very carefully on a winter evening, some say you can still hear faint applause… and a Cornishman with kind eyes whispering to his young actors:

“That’s it, my dears. Once more, with feeling.”

Instead, he took a job nobody wanted.

Medical superintendent at the Royal Earlswood Asylum for Idiots near Redhill, Surrey. Four hundred residents with intellectual disabilities. A place the Lunacy Commission had condemned for its horrific conditions.

When John Langdon Down walked through those doors, he found hell on Earth.

Fifteen to twenty children crammed into single rooms. Corporal punishment was routine. Beatings for minor infractions. Hygiene was abysmal. Typhus and tuberculosis ravaged the residents. The mortality rate was staggering.

These were children. Human beings. Treated like animals.

Most doctors would have kept their heads down, collected their salary, and looked away.

John Langdon Down did the opposite.

He fired staff. Hired new ones who actually cared. Made hygiene the top priority. Banned all physical punishment—completely. Not reduced. Banned.

He insisted residents eat with knives and forks, treating them with the dignity they deserved. Good behavior was rewarded. Bad behavior was met with patience, not violence.

He introduced activities. Taught them crafts, hobbies, diction. Gave them purpose.

And then he did something revolutionary.

He photographed them.

Over 200 photographs. But these weren’t clinical images documenting “specimens.” They were portraits.

His patients wore elegant clothing. Posed with dignity. Looked directly at the camera as individuals worthy of respect.

In an era when people with disabilities were hidden away, denied basic humanity, these photographs declared something radical: These are people. Look at them. See them.

The reforms worked. Within years, Earlswood became world-famous. The Lancet published a glowing article praising the transformation.

But John Langdon Down wasn’t finished.

In 1866, he published a paper called “Observations on an Ethnic Classification of Idiots.” The title hasn’t aged well—it reflects the problematic racial theories of his time. But buried in that paper was something groundbreaking.

He identified a specific group of patients—about 10% of residents—who shared distinctive physical characteristics. Round faces, almond-shaped eyes, flat nasal bridges, short stature.

He was the first person to systematically describe what would eventually be called Down syndrome. The first to recognize it as a distinct condition, not just general intellectual disability.

But recognition wasn’t enough. He wanted more for these children.

John Langdon Down had a wife, Mary Crellin, whom he’d married in 1860. She worked alongside him at Earlswood, unpaid, teaching children, organizing activities, providing care.

Together, they asked the Lords of Earlswood for two things: compensation for Mary’s work, and funding to display residents’ artwork at an exhibition in Paris.

Both requests were denied.

So in 1868, John Langdon Down resigned. And he used his own money to buy something extraordinary.

A villa in Teddington, between Hampton Wick and Teddington, just outside London.

He called it Normansfield. Named after his lawyer, Norman Wilkinson, who helped secure the mortgage.

This wasn’t going to be an asylum. It was going to be a home.

The first 18 residents were children of wealthy families—lords, physicians, high-ranking officers. John needed their money to make the project financially viable. But every child received the same care regardless of who their parents were.

Normansfield was built to the highest standards of comfort and hygiene. Residents received personalized education. They learned horseback riding, gardening, crafts, music, and elocution.

The grounds included stables, gardens, and a farm where residents worked, learning practical skills and contributing to their community.

But John Langdon Down wanted to give them something more.

In 1877, he began construction on a theater.

Not a small room. A grand entertainment hall with a proscenium stage, ornamental ironwork, elaborate painted panels of plants and birds. Botanical artwork attributed to famous Victorian painter Marianne North decorated the front of the stage.

The theater could seat 300 people. It had a balcony with ornamental iron railings. A “sunburner” ventilation system in the ceiling.

It opened in 1879 in the presence of the Earl of Devon.

Residents performed plays. Staff put on shows. Sunday services were held there with John Langdon Down himself at the lectern.

For people society said couldn’t learn, couldn’t develop, couldn’t contribute—John Langdon Down built them a theater.

He died suddenly in 1896 at age 67, having transformed care for thousands of people.

His sons, Reginald and Percival—both trained physicians—continued his work at Normansfield. Ironically, Reginald’s own son was born with Down syndrome in 1905. The family raised him at home with love and dignity, just as their grandfather would have wanted.

Normansfield continued operating until 1997, caring for people with intellectual disabilities for over a century.

Today, the building still stands. It’s now the Langdon Down Centre, home to the Down’s Syndrome Association’s national headquarters.

The Normansfield Theatre—Grade II* listed—has been meticulously restored. It houses the largest collection of fully restored Victorian scenery in the UK.

You can visit it. Walk on that stage. See the ornamental panels. Stand in the space where people once told they had no value performed for audiences, expressed themselves, lived with dignity.

In 1961, genetics experts wrote to The Lancet asking that the offensive term “Mongolism” be dropped. They approached John Langdon Down’s grandson, still running Normansfield, and asked if they could use the family name instead.

He agreed.

In 1965, the World Health Organization officially adopted “Down syndrome.”

The name doesn’t describe the condition. It honors a man who saw humanity where others saw hopelessness.

A man who photographed patients in elegant clothing when others chained them in cells.

A man who banned beatings when violence was standard practice.

A man who built a theater for people society said couldn’t learn.

John Langdon Down proved something the world desperately needed to hear:

Everyone deserves dignity. Everyone deserves education. Everyone deserves to be seen.

Next time you hear “Down Syndrome,” remember:

It’s not about going down. It’s about a Victorian doctor who lifted people up.