February 05, 202

Once upon a time, back in the good old days of television’s fictional Marcus Welby, MD, being a doctor was more than a job. It was an identity — part calling, part covenant. Your white coat was armor, your title a shorthand for authority, respect, and trust. Communities deferred. Bankers approved loans without blinking. Patients sent holiday cards and baked pies.

nullLucy Rice, MD

Lucy Rice, MD, remembers the days when she and her brother couldn’t walk into a pharmacy without someone recognizing them as “Dr Kuykendall’s kids.” Her father, Samuel Kuykendall, MD, is a retired OB-GYN who delivered thousands of babies in their rural community. “We grew up with two refrigerator-sized deep freezers,” she said, “because my dad would come home with hundreds of chess pies, which he loved.”

“Now, that culture is changing,” she said.

During her 10 years as an OB-GYN in a private practice, Rice said she felt an overall lack of appreciation, leading to burnout. She elected to leave and start a family. She will soon be opening a concierge medical practice, minus the obstetrics.

null

Rice always wanted to go into medicine, but with a husband who often travels for work, she found it difficult to meet the job’s demands. “My mom always says dad lived to work, and that nowadays we work to live,” she added. “I’m good at what I do, and I have a passion for it. But I also have this passion for my family.”

null

null

She’s not the only doctor to see how the medical career of previous generations is no longer possible.

The Social Contract Has Been Revised

To understand how we got here, Tania Jenkins, PhD, medical sociologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, suggested that we look at the “social contract” between medicine and society.

nullTania Jenkins, PhD

She explained that for most of the twentieth century, society had an expectation that physicians were competent, moral, and altruistic — putting patients’ needs above their own. In return, society rewarded them with trust, deference, and prestige.

That contract hasn’t vanished, she said, but the exchange rate has been revised.

“The physicians’ end of the bargain hasn’t changed,” Jenkins said, “but the return on making those investments appears to be changing for a number of reasons.”

Some of that erosion stems from corporatization. Doctors are no longer the sole decision-makers in healthcare with insurance companies and corporate chains often dictating the terms of care. “There are corporate interests. There are government interests. And there is increasing patient consumerism,” Jenkins said, a kind of skeptical “shopper mentality.” Bill Fuqua, MD

“My father would have had a seizure if you called his patients consumers,” said Bill Fuqua, MD, retired anesthesiologist, fifth-generation physician, and Rice’s uncle. “He said the three A’s of medicine were availability, affability, and ability — and they’re in that order.”

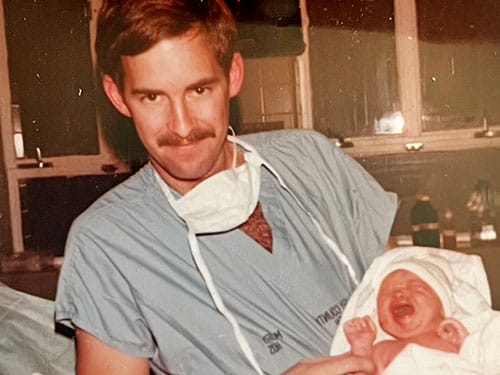

Fuqua said that when he was a resident there was no talk of one’s “lifestyle” or “work-life balance.” “My chairman would say that the only bad thing about going on call every other night is that you miss every other emergency,” he said with a laugh. “We worked harder than anyone else in the hospital, but we took pride in it, and you learned to be selfless, and they just don’t drive that lesson into people anymore.”Bill Fuqua’s grandfather, Dr Ernest Mitchell Fuqua

Fuqua admitted this sounds almost masochistic by today’s standards, but he also believes that it was — and still should be — necessary and expected. “That’s what you signed up for,” he said. “Read the Hippocratic Oath. I took that Oath and I missed out on a lot of my family’s life.” But for his generation, medicine was what his father referred to as a “jealous mistress,” one that demanded everything but repaid in respect. “There was an egotistical aspect of me going into medicine: I wanted to be respected like my father,” Fuqua said.

null

Joseph Weigel, MD, retired general internist and second-generation physician, had a different perspective. He said he wouldn’t want the students he teaches today to go through the same grueling experiences he had in the early 1980s. “When I trained, there really weren’t any rules,” he said. “There was no real sense that there were mental health issues. There was no real sense that it was maybe a bad thing.”

Weigel acknowledges how different medicine has become. “I think many students look at this as a job. When it’s a job and not a profession, your level of commitment is different. Most of the physicians in my generation would say that being a doctor defined who they were as a human being.”

The Tradeoffs That Changed Medicine

Weigel and Fuqua stress that today’s physicians aren’t lazy, but they are overburdened and disillusioned. They see the younger generation enter medicine with noble intentions, but the realities of electronic health records, prior authorizations, and relative value unit quotas have changed the game.Joseph Weigel, MD

Though younger physicians have more opportunities to prioritize work-life balance, especially at larger healthcare organizations, there’s a tradeoff, explained Joshua Gottlieb, PhD, medical economist and professor at The University of Chicago, Chicago.

“ There is a lot of administrative complexity that is more easily handled in a large firm,” Gottlieb said. “But being a part of a larger organization often involves less autonomy.” Considering that a 2025 report from the National Bureau of Economic Research announced employment in healthcare corporations is the largest industry in the US, physicians will continue to struggle with that loss.

Clearly, t he days of the solo practitioner, the family doctor with an office above the drugstore, are all but over. Private practice, once a cornerstone of medical identity, has become increasingly financially and logistically untenable, especially for primary care physicians.

In a 2023 press release, American Medical Association (AMA) Former President Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, MD, MPH, explained, “The AMA analysis shows that the shift away from independent practices is emblematic of the fiscal uncertainty and economic stress many physicians face due to statutory payment cuts in Medicare, rising practice costs, and intrusive administrative burdens.”

Younger doctors, often graduating with six-figure debt, are understandably reluctant to take on more financial risk. In 2025, the average medical student debt, including undergraduate debt, was $246,659 but can be greater than $300,000 if attending a private institution.

null

“When I graduated from medical school in 1981, it cost a total for 4 years of about $32,000,” Weigel recalled. “When you have the level of debt that these kids have coming out, no banker is going to finance them. When I started practice in 1985, almost all physicians owned their own business and had people working for them. That’s true for almost no one now.”

Stagnating salaries haven’t helped the situation. Medscape’s Physician Compensation Report 2025found that compensation rose by 2.9% on average from 2024, on par with the prior 2 years. And 52% of respondents felt they are not fairly compensated for their work.

Does today’s compensation compete with physician earnings, say, 50 years ago?

The average doctor in solo practice earned $48,900 in 1975 and worked 58 hours per week, according to this analysis. That’s equal to roughly $293,000 in 2025.

The average doctor made $374,000 in 2025 and worked 50 hours a week, according to Medscape’s Physician Compensation Report, but that higher compensation today comes with student debt, no independence, and tons more admin.

Who had the better deal?

Specialties and the Specialness Gap

If a lack of autonomy dilutes access to prestige, specialization further fractures it.

This is nothing new, said Michael Barnett, MD, MS, internist and assistant professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. “This primary care/specialty care gradient is a long-standing bias that existed since specialists existed and our modern reimbursement system was enshrined in the healthcare system,” he said. “It’s been in place for a very long time.”Michael Barnett, MD, MS

Barnett said that among doctors, this idea of prestige and specialty is financial. He points out that primary care and pediatric physicians are viewed as the least prestigious simply because they are among the lowest paying medical specialties and among the least competitive residenciesto get into.

Primary care also doesn’t drive as much revenue in a hospital system compared to specialties like cardiology, orthopedics, or oncology. This can be a source of grievance for physicians outside of those high profit-producing specialties.

“A lot is expected of us and we have an undeniably important role for population health,” said Barnett, “but our political clout is very much rooted in the nonhealth-based reimbursement system, which has much more to do with the idiosyncrasies of our economy and healthcare system than it does with public health.”

Jenkins’ soon-to-be published research suggested that specialized physicians also experience less burnout. For a recent study, she observed two pediatric clinics and a children’s surgical services clinic. These are places where she said, “surgeons operate on infants as small as 500 grams with life-threatening conditions and where the stakes couldn’t possibly be higher.”

Jenkins had every reason to believe that the surgeons would experience more burnout based on the intensity and number of hours they worked, but it turns out they were the happiest people she studied. Why?

“They had such esoteric expertise that was very well valued at the societal level,” Jenkins said. They were in a position to command more respect at the organizational level, given more autonomy to run their affairs and, at the patient level, afforded more trust. “Because they are the only people that can do these very specific procedures, it leads patients to question them less than the standard pediatrician who fields all sorts of questions all day long, like the safety of vaccines.”

Paternalism and Prestige

For some physicians — even those who specialize — the idealistic image of Marcus Welby is part of the problem.

“There are some of us who were never considered prestigious in medicine regardless of the position we held,” said Jenna Lester, MD, dermatologist, assistant professor at the University of California, San Francisco, and second-generation physician. “More than prestige, I just look for basic respect,” she said. “And that has always been elusive for certain doctors, especially Black physicians like myself.”

Lester recalls hearing how some of her mother’s patients would question her plan for care, asking if the medical student in the room agreed. In Lester’s view, things haven’t progressed that much; it’s systemic.

She points out that when the AMA was founded in the mid-1800s, Black physicians weren’t allowed to join. That exclusion wasn’t just symbolic — she said it shaped the professional hierarchy for generations.

Consequently, Lester said that if a physician complains about there being a lack of prestige in medicine, what they’re probably referring to is that there’s less paternalism in medicine, which she views as a good thing. “Doctors were used to everyone falling to their knees anytime they said anything,” she said. “There was a clear hierarchy.”

Inquiring for clarity and questioning care can be two very different things. “It doesn’t bother me if patients ask me questions or to explain and justify. [But] skepticism toward science has been on the rise. It certainly culminated with the COVID pandemic but has continued today with vaccines and such,” said Jenkins, who has published a number of articles on the toll this has taken on physicians.

Weigel agrees. “In the country right now, there’s a general loss of respect for science, and loss of respect for individual physicians’ judgment,” he said. “I think that attitude plus the availability of either bad or good information on the internet has really changed the way people look at individual clinicians.”

null

The Next Chapter: Redefining What Matters

When Weigel retired, he made the front page of his small-town newspaper. He received awards and warm send-offs — public acknowledgments of a career both grueling and meaningful. “I’m very happy that I practiced when I did, even though it was incredibly arduous,” he said. “The part of medicine that was most rewarding to me was that I truly felt like a shepherd with his flock. There was a sense that you were responsible for people and that they depended on you.” He added: “It just isn’t the same anymore.”

The profession has evolved — and with it, perhaps, the values that define prestige. Where once it was measured in status, autonomy, and deference, might now be tied to balance, sustainability, and self-preservation. Younger doctors may not see themselves as shepherds, but they are trying to preserve the heart of what medicine has always been: service.

The old model of medicine, for all its inequities, offered a profound sense of purpose. It was a covenant between doctor and patient built on trust. Today, many physicians feel that contract has been rewritten by bureaucracy, big business, and consumerism. For Weigel and his generation, medicine was a calling that consumed them. For the next, it may be something they must continually reclaim.