In the bustling city of Agra, under the shadow of the Taj Mahal, a young man named Mukul Bhatia grew up with a deep sense of curiosity about the world beyond his textbooks. Born in the mid-1950s on 18 Th of February 1958 to be exact, into a modest family, Mukul was always drawn to stories of India’s freedom fighters and the ancient wisdom of its culture. “Why study medicine just to sit in a clinic?” he would often muse to his friends during late-night discussions at Sarojini Naidu Medical College, where he pursued his MBBS in the late 1970s. Little did he know, his path would lead him far from the comforts of urban life, into the heart of India’s remote tribal regions.

By 1979, fresh out of medical school at the age of 24, Mukul faced a crossroads. Many of his classmates dreamed of lucrative practices in big cities or abroad. But Mukul had been influenced by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), an organization he joined during his college years, inspired by its emphasis on nationalism, discipline, and selfless service. “Medicine isn’t just about healing bodies,” he confided to his mentor, a senior RSS pracharak, during a shakha meeting. “It’s about healing the nation. Our vanvasi brothers and sisters in the Northeast are forgotten—cut off from education, health, and even basic dignity. I want to go there, not as a doctor, but as a bridge builder.”

The mentor nodded thoughtfully. “Mukulji, this is the true essence of RSS—karuna and karma combined. But Assam’s tribal areas are rugged, isolated. Are you ready to leave everything behind?”

With a determined smile, Mukul replied, “If not me, then who? Nationalism isn’t a slogan; it’s action. And creativity? That’s turning challenges into change.”

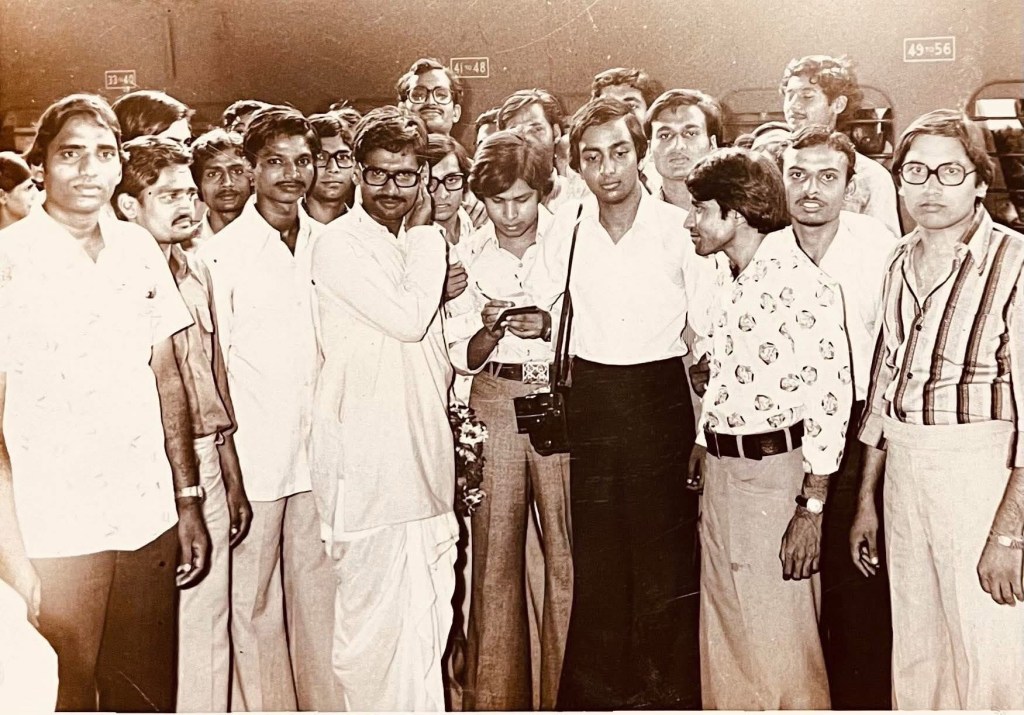

Word of his decision spread like wildfire among the medical community in Agra. On that fateful Sunday, August 19, 1979, hundreds of fellow doctors, volunteers, and well-wishers gathered at Agra Railway Station for his farewell. The platform buzzed with energy—banners fluttering with messages like “Mukulji: Symbol of Nationalism and Creativity.” As the train to Assam chugged in, a senior doctor clasped Mukul’s hand. “You’re not just going to treat illnesses, beta. You’re igniting hope in the vanvasi heartlands.”

Mukul, clutching a simple bag with his stethoscope and a few books on tribal health, turned to the crowd. “Friends, this isn’t goodbye. It’s a promise. The RSS has taught me that India is one family—from Agra’s streets to Assam’s forests. I’ll carry your spirit with me.”

Cheers erupted as he boarded the train, waving until the station faded into the distance. That moment, captured in a faded photo with the inscription “Mukulji RSS—the symbol of nationalism and creativity,” became a legend among RSS circles, inspiring countless others to choose service over security.

Arriving in Assam’s vanvasi regions—dense forests and remote villages inhabited by tribal communities—Mukul dove headfirst into his role as an RSS campaigner. He set up makeshift clinics, traveling on foot or by boat to reach areas plagued by malaria, malnutrition, and lack of education. “Doctor sahab, why come so far?” a tribal elder once asked him during a village meeting in the Karbi Anglong district.

Mukul, sitting on a bamboo mat, shared a cup of rice beer. “Because you’re my family. The RSS believes in ‘Ekatmata’—one soul. If one part suffers, the whole body aches. Let’s build a school here, teach hygiene, and grow together.”

Over the next decades, his work evolved. In the 1980s and 1990s, he expanded health camps across Northeast India, combating diseases while promoting cultural integration through RSS programs. By the early 2000s, he became a key figure in the Ekal Vidyalaya Foundation, an RSS-affiliated initiative focused on single-teacher schools in tribal areas. As the architect of Ekal’s health wing, Arogya Foundation of India, he coordinated nationwide efforts, training local volunteers and distributing immunity boosters during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Health isn’t pills alone,” he’d say in his talks, even at prestigious venues like MIT in 2015. “It’s empowerment. In remote villages, we’ve reached over a million people, blending modern medicine with traditional wisdom.”

Today, as National Coordinator of Arogya Foundation, Dr. Mukul Bhatia—now in his late 60s—continues mentoring young doctors and volunteers. His life, a blend of dedication and innovation, has touched millions, from Assam’s hills to rural heartlands across India. In quiet moments, he reflects on that 1979 train ride: “It wasn’t sacrifice; it was purpose.” Mukulji’s story reminds us that true nationalism blooms not in grand speeches, but in the quiet acts of service that bind a nation together.

![[Explore 20260306] Leica M-EV1 with Thypoch EUREKA 50mm f/2 full frame [Explore 20260306] Leica M-EV1 with Thypoch EUREKA 50mm f/2 full frame](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/55129318502_ef078425b6_s.jpg)