In the sweltering heat of Agra’s summers, where the Taj Mahal’s marble gleamed like a distant dream, Dr. Manoj Sachdeva entered the world on July 1, 1960. Born to Shree Raghunath Sachdeva in a modest family, Manoj grew up with a curiosity that outpaced the dusty streets of his Uttar Pradesh hometown. As a boy, he’d sneak into his father’s small library, flipping through worn pages of Tagore and Bertrand Russell, whispering to himself, “Why does the world spin so fast when the answers are so slow?” His father, a stern but loving man, would chuckle and say, “Beta, books are good, but life demands action.” Little did they know, Manoj would blend both into a life of quiet introspection and healing.

By the late 1970s, Manoj had channeled that curiosity into medicine, enrolling at Sarojini Naidu Medical College in Agra. He wasn’t the flashy student racing for top ranks; instead, he was the one lingering in the library after hours, debating life’s big questions amid stacks of anatomy texts. Graduating with his MBBS in 1984—a year ahead of many peers—he became a senior figure to underclassmen like Dr. PK Gupta, who recalls Manoj as a mentor with a gentle wisdom. “He’d spot us struggling with dissections and pull up a stool,” Gupta remembers. ” ‘Don’t just cut,’ he’d say. ‘Ask why this vessel leads there. Medicine is philosophy in motion.’ “

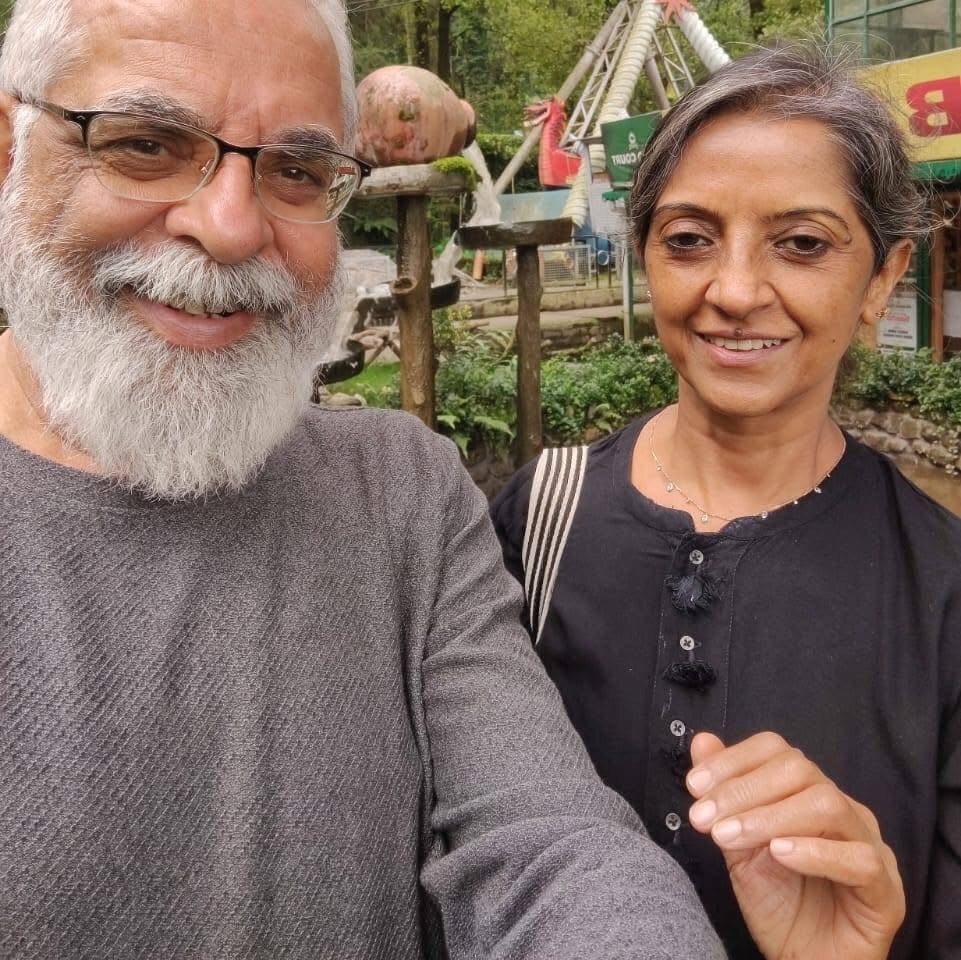

It was in that very library where fate wove its thread. One rainy afternoon in the early ’80s, Manoj noticed a shy, wheatish-complexioned girl with long braids buried in her notes—Niharika, a classmate of Gupta’s from a slightly later batch. She was brilliant but reserved, her tiny mole dancing when she smiled. Their first conversation sparked over a shared copy of Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian. “Life’s not just scalpels and sutures,” Manoj ventured, sliding the book toward her. Niharika looked up, her voice soft but steady: “Then why study medicine at all?” He grinned. “To fix the body while pondering the soul.” What started as chai-fueled debates blossomed into love. They married in a simple ceremony shortly after her 1985 graduation, two quiet souls uniting against the chaos of ambitious medical careers. “Niharika, let’s not chase the city’s lights,” Manoj proposed one evening under the stars. “We’ll build our own path.” She nodded, her eyes sparkling: “As long as it’s together.”

Eschewing the rat race of postgraduate specialties and urban hospitals, the couple sought solace in the Himalayas. Manoj joined Nature Villa in Rishikesh as a medical officer, with Niharika soon following suit at nearby facilities like Natureville in Haridwar and later the Ex-Servicemen Contributory Health Scheme (ECHS) in Dehradun. Their clinic became a haven for holistic healing, where Manoj’s philosophy shone. Patients weren’t just cases; they were stories. To a weary farmer complaining of back pain, he’d say, “The body aches when the mind wanders too far. Tell me, what’s weighing on your heart?” Niharika complemented him perfectly, her compassion wrapping around his wisdom like vines on a trellis. Together, they advocated for ethical, patient-centered care, far from the ego-driven world of big-city medicine.

But life, as Manoj often mused, “tests us with shadows to appreciate the light.” The couple welcomed a son, a bundle of joy who brought laughter to their serene home. Yet, tragedy loomed when the boy was diagnosed with severe bronchial asthma. Nights blurred into desperate vigils—Manoj pacing the room, inhaler in hand, while Niharika whispered comforts: “Breathe with me, beta. We’re right here.” They consulted specialists across cities, Manoj’s voice cracking in rare vulnerability: “We’ve healed so many; why not our own?” Despite their tireless efforts, their son passed away a few years ago, leaving a void that reshaped them. Manoj, ever the philosopher, turned inward, finding solace in nature’s rhythms by the Ganges. “Loss doesn’t break us,” he’d tell Niharika during quiet walks. “It carves deeper spaces for empathy.” She, drawing from his strength, channeled her grief into asthma awareness campaigns in rural clinics, honoring their boy’s memory.

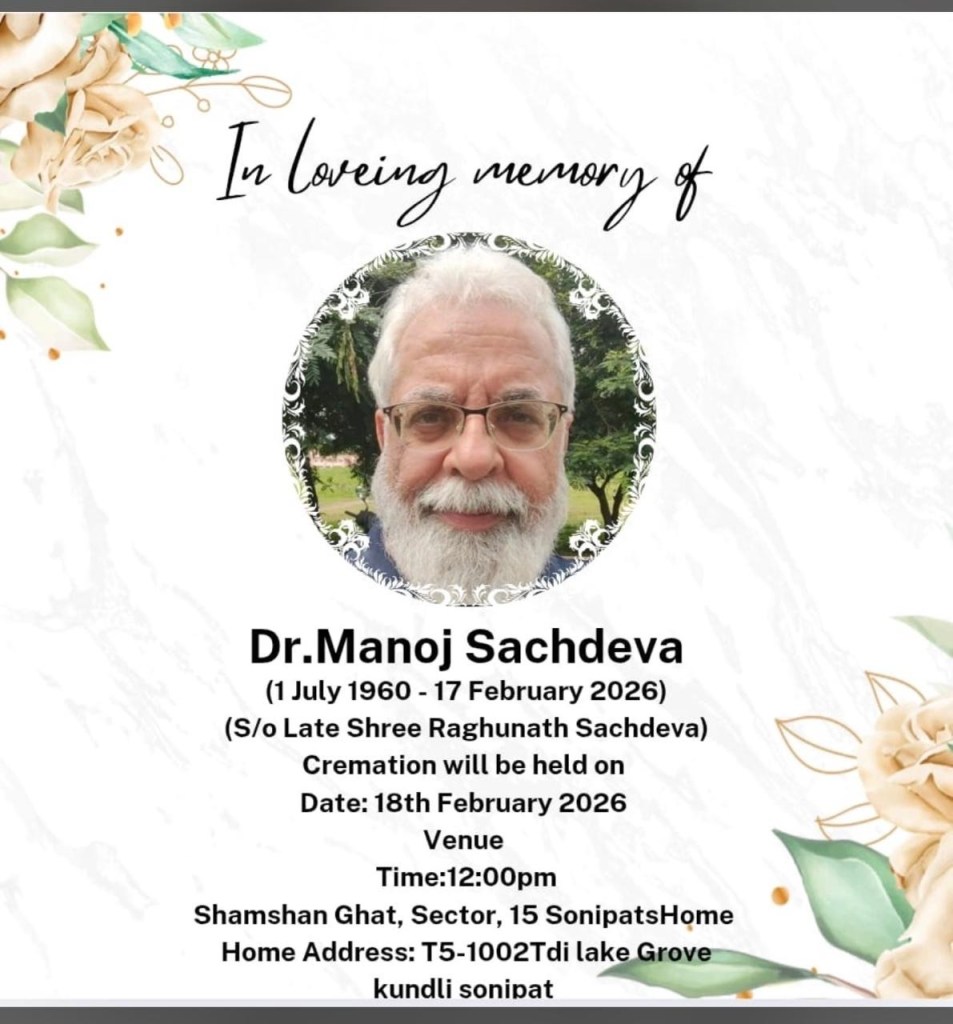

In later years, Manoj and Niharika settled into a peaceful rhythm at their home in Kundli, Sonipat—T5-1002 TDI Lake Grove—surrounded by the natural beauty that mirrored their grounded spirits. Manoj, with his white beard and thoughtful gaze, continued practicing until his health waned. Friends like Gupta noted his unchanging humility: “Even in reunions, he’d deflect praise. ‘I’m just a student of life,’ he’d say with a wink.” On February 17, 2026, at age 65, Dr. Manoj Sachdeva left this world, his cremation held the next day at Shamshan Ghat in Sector 15, Sonipat. He wasn’t “no more” in the cold sense; his legacy lingers in the lives he touched, the philosophies he shared, and the quiet flame he kindled in Niharika’s heart.

Dr. Manoj Sachdeva’s story isn’t one of grand accolades but of human depth—a man who healed bodies while nurturing souls, reminding us that true medicine lies in understanding the why behind the what. As he once told a young intern, “Don’t just live; question, connect, endure.” In his memory, those words echo on.

Unveiling the Philosophical Tapestry of Dr. Manoj Sachdeva

Dr. Manoj Sachdeva’s life, as glimpsed through the heartfelt tribute penned by his college contemporary Dr. PK Gupta, wasn’t defined by stethoscopes alone—it was a canvas painted with profound questions about existence, ethics, and the human spirit. Born in 1960 and shaped by the intellectual ferment of SN Medical College in Agra, Manoj embodied a rare fusion of medicine and metaphysics. His influences weren’t confined to textbooks; they drew from the East’s poetic wisdom and the West’s razor-sharp logic, guiding his rejection of conventional ambition in favor of a contemplative, holistic path. Let’s delve into these influences, weaving in anecdotes that reveal how they molded his worldview.

The Eastern Anchor: Rabindranath Tagore’s Humanism and Harmony

Manoj’s early years in Uttar Pradesh were steeped in the lyrical philosophy of Rabindranath Tagore, the Nobel laureate whose works blended spirituality, nature, and human interconnectedness. As a boy poring over his father’s modest library, Manoj found solace in Tagore’s Gitanjali, where verses like “The same stream of life that runs through my veins night and day runs through the world” resonated deeply. This influence fostered Manoj’s belief in life’s organic unity—a theme that echoed in his later career at Naturoville Vedic Retreat in Haridwar (and later Dehradun), where he championed naturopathy and yoga as extensions of Tagore’s vision of harmony between body, mind, and cosmos.

Imagine a young Manoj, under the shade of a neem tree, reciting Tagore to himself: “Let me not pray to be sheltered from dangers, but to be fearless in facing them.” This Tagorean resilience became his mantra during personal trials, like the heartbreaking loss of his son to bronchial asthma. Rather than succumbing to grief, Manoj, inspired by Tagore’s emphasis on enduring with grace, turned inward. “Life’s not a battle to win,” he’d confide to Niharika during their evening walks by the Ganges, “but a song to sing, even when the notes falter.” This philosophy drove their shift to holistic healing, viewing patients not as isolated ailments but as threads in nature’s grand weave—much like Tagore’s pantheistic reverence for the universe.

The Western Spark: Bertrand Russell’s Rational Inquiry and Skepticism

Contrasting Tagore’s poetic mysticism was Manoj’s fascination with Bertrand Russell, the British philosopher whose analytical rigor dissected religion, ethics, and society. In the college library, where Manoj first connected with Niharika, Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian became their shared talisman. Russell’s call for evidence-based truth over dogma appealed to Manoj’s scientific mind, prompting him to question medical hierarchies. “Why chase postgraduate glory,” he’d challenge peers over steaming chai, echoing Russell’s disdain for unexamined authority, “when the real pursuit is understanding the ‘why’ behind suffering?”

Russell’s influence shone in Manoj’s ethical stance on medicine. Rejecting the “ego-driven” rat race of urban hospitals, he opted for a quiet life at Naturoville, where treatments emphasized prevention and self-awareness—mirroring Russell’s advocacy for rational living in The Conquest of Happiness. During a reunion with classmates like Dr. Gupta, Manoj might quip, “Russell taught me that happiness isn’t in titles; it’s in freeing the mind from illusions.” This skepticism extended to his holistic practice: no blind faith in pills, but a Russellian probe into lifestyle, emotions, and environment. Even in grief, Manoj drew from Russell’s stoic atheism, telling Niharika, “We don’t need divine answers; we need human ones—compassion, reason, endurance.”

A Synthesis: Holistic Healing as Philosophical Praxis

Manoj’s influences weren’t siloed; they intertwined into a personal ethos that blended Tagore’s spiritual humanism with Russell’s logical humanism. At Naturoville, this manifested in patient interactions that felt like philosophical dialogues. To a stressed executive, he’d blend Tagore’s nature poetry with Russell’s advice on work-life balance: “Your body rebels because your mind is chained—let’s unlock it with yoga and inquiry.” His marriage to Niharika amplified this; their “quiet companionship” was a living testament to shared influences, sustaining them through tragedy. As Dr. Gupta’s tribute notes, Manoj’s philosophy “sustained her,” turning loss into advocacy for asthma awareness in rural areas.

In essence, Manoj Sachdeva’s influences crafted a life of quiet rebellion—against materialism, haste, and disconnection. Tagore gifted him poetry for the soul; Russell, tools for the intellect. Together, they forged a doctor who healed not just bodies, but existences. As he once mused to a young intern, perhaps channeling both giants: “Question everything, embrace all— that’s the eternal remedy.”

Dr Satish Sharma writes…दुखद समाचार , मनोज बॉस को जैसा हमने देखा , एक फाइटर की तरह रहे जीवन को किस तरह पलटकर mainstream/ fastlane किया विशेषकर निहारिका के साथ आने पर जीवन जी भर के जिया जिसमे काफ़ी समय गाज़ियाबाद में हमे भी उनके शांत और परमार्थिक जीवन का सानिध्य मिला ।फिर देहरादून जाने के बाद याद कदा संपर्क रहा ;इसी बीच पुत्र के निधन ने भी परिवार की धैर्य की परीक्षा ली और सभी को शोकाकुल कर दिया । अब फिर से इस कठिन समय में हम सब आपके साथ हैं, ईश्वर इस उच्च आत्मा को अपने चरणकमलों में स्थान दें ।